Emma, Bravó!

By Betsy Holmquist Countless stories surround Emma Bravo Lommasson ’33, M.S. ’39. Nearly ninety-three years of them. And Emma tells some of the best. This endearing and enduring woman, whose presence at UM spans more than seventy years, still cannot believe that a building on campus—the Emma B. Lommasson Center (formerly the Lodge)—is named in her honor. Emma will tell you that she just did her job. That she worked hard. And, along the way, tried to make other people happy. “Isn’t that the way,” she says, “that you keep happy in life?”

Countless stories surround Emma Bravo Lommasson ’33, M.S. ’39. Nearly ninety-three years of them. And Emma tells some of the best. This endearing and enduring woman, whose presence at UM spans more than seventy years, still cannot believe that a building on campus—the Emma B. Lommasson Center (formerly the Lodge)—is named in her honor. Emma will tell you that she just did her job. That she worked hard. And, along the way, tried to make other people happy. “Isn’t that the way,” she says, “that you keep happy in life?”

In 1942 a thirty-one-year-old Emma was hired to teach navigation and civil air regulations to future Air Force pilots stationed on the UM campus—subjects she knew nothing about. Emma stayed ahead of her students by studying all day for the two-hour nightly classes. “I’d never even been in an airplane,” she admits. “I worked hard, trying to imagine what it was like to fly.” One wintry day the orders came to take her up. “All my boys came to the airport,” she says. “They put a flight suit on me, the helmet, the goggles. I was just ready to step into the plane when they attached a parachute to my chest. ‘Do you know how to work a parachute?’ someone asked. ‘No,’ I replied, ‘Who cares?’” Emma climbed into the open cockpit behind pilot Frank Wiley. He gave her an instruction: “When you start to get sick and want to go down, pat your head.” Up they went. Wiley put the plane through all possible maneuvers. The ground and mountains were covered in snow. The sky was white. Emma didn’t know if she was right side up or upside down. But she never patted her head. After they landed, Emma faced one more challenge—she had to drink a cup of coffee and eat a piece of pie to prove she wasn’t airsick. Emma had never been a coffee drinker, still isn’t. But she drank a cup and ate a piece of pie in front of all the men. “The next night,” she says, “ I knew I was a much better teacher.”

Emma was always hard on herself, a trait that allowed her to put pressure on others she felt could do better. One year a transfer student from Custer County Community College fell under Emma’s scrutiny when she noticed that his straight “A” record was marred by a “B” in a Spanish course. “Emma was crushed and I know felt much worse about the B than I did, and I felt badly,” this former student reports. “She spent some time consoling me and urging me to get the string going again. I made it to graduation the following spring with one more B. Despite these two B’s, Emma congratulated me for doing well, and cautioned me to sustain the effort as I went off to graduate school. Nearly thirty years later,” President George Dennison continues, “Emma welcomed me back to campus as president almost as if she had expected that to happen.”

President Dennison’s current home was Emma’s residence for a time when she was a student. Then, 1325 Gerald was owned by Dr. N.J. Lennes, the head of UM’s math department. He employed Emma as an assistant for his math classes and she lived with Dr. and Mrs. Lennes and Marie, “the maid,” as she was called by Mrs. Lennes. Marie and Emma were the same age and wanted to be friends. Mrs. Lennes preferred that the girls kept their distance. Emma was learning to roller skate and one summer evening invited Marie outside to try it herself. Unfortunately, Marie fell and hurt her arm. Mrs. Lennes was livid. The girls were forbidden to ever talk again. “But,” Emma explains,” we’d open our upstairs windows and talk to each other that way.”

Emma worked hard for Dr. Lennes, teaching a class for him each quarter, correcting his tests, and editing his math workbooks. One quarter she taught all his classes. “I learned a lot from him,” she quickly adds, always admitting that the harder she worked, the more she learned and the better person she became.

From her youngest days, Emma worked hard. She was the first woman from Sand Coulee, Montana, to attend UM. The oldest of three girls born to Italian immigrants, Emma spoke only Italian until first grade. “I learned English properly,” Emma says, of her first year in school. “My teacher would write the words I needed to learn on the board and make me pronounce them until I got them right. I struggled with those ‘th’ sounds.” As with most struggles she’s encountered, Emma triumphed. Her English is flawless. And, she still speaks and reads Italian.

When she was seventeen, Emma boarded the train for the overnight journey to Missoula and the State University of Montana. A resident of North Hall that fall of 1929, she soon became a senior assistant to the housemother, Mrs. Brantly. Emma led the girls into the dining room—now the Presidents Room of Brantly Hall—each day for lunch and dinner. The girls dressed for meals. A host and hostess sat at each table. There were tablecloths and linen napkins. “We learned manners!” Emma declares and fondly recalls the frequent visits of Mary Clapp, the wife of Charles H. Clapp, UM’s fifth president. Mrs. Clapp came to teach the coeds etiquette and Emma was a rapt pupil. To this day Emma can eat a piece of chicken without touching it with her fingers—thanks to Mrs. Clapp. “I never have chicken without thinking of her,” Emma laughs. “We respected her. She impressed me a lot.”

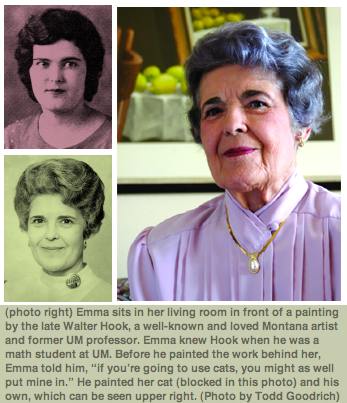

By her senior year, Emma was deeply involved in campus activities. In the 1933 Sentinel yearbook a serious Emma Bravo appears in the photos for Mortar Board and the governing body of the Associated Non-Fraternity and Non-Sorority students. Her erect posture, thick, wavy hair, dark eyebrows, and prominent cheek and jawbones quickly catch the viewer’s eye.

A slight grin appears on Emma’s face in the Hi-Jinx Committee photo. That year she had managed “Must We Go On,” a musical revue of take-offs on campus life. Emma presided over May Fête activities that year, too, as Queen of the May.

Emma received a bachelor’s degree in math from UM in 1933 and returned to Sand Coulee for six years to teach. She remembers her first day teaching high school algebra. “I looked at my students and said, ‘You’re all going to like algebra when I’m done teaching you.’ I wanted them so to like it. At the end of the year one student came to me and admitted he just didn’t like algebra. I told him I understood completely, but that I admired him so for trying. I learned from that experience that you can work hard with a student, but if it’s not in their nature, they’re just not going to get it.” This sense of compassion and acceptance of the difficulties others face came early to Emma and allowed her to offer reassurance without judgment to countless people along the way.

“You were my role model from the very beginning,” a former Angel Flight member related to Emma just a few years ago. Emma was the sponsor for this Air Force ROTC drill team for eighteen years and had worried all that time that the girls thought her a “fuddy-duddy.” Emma admits to interceding several times for girls who were too frightened to go before the Dean of Women, Maurine Clow, in the ’60s and ’70s “Why aren’t you the Dean of Women?” she was frequently asked.

Dick Joy ’54 from London, Ontario, Canada, remembers meeting Emma when he was thirteen years old. Joy’s father worked with Emma’s husband, Tom, in the U.S. Forest Service and one evening the Lommassons invited the Joy family to dinner. “Her flashing eyes,” Joy recalls, “her dark-haired beauty really made an impression on me.” When he returned to campus as a student six years later, Emma was the assistant registrar. “She took the sons and daughters of Forest Service employees under her wing,” Joy says. “We could go to her office in the old men’s gym any time we had questions or needed help.” This past May at Joy’s fiftieth class reunion, he proudly escorted Emma Lommasson to his table at his class banquet. Many of his classmates, now in their early seventies, came by to pay her tribute.

Students who worked with Emma often learned more than their jobs required. UM’s Associate Registrar Laura Wolverton Carlyon ’63, M.P.A. ’87, began working for Emma at ninety cents an hour while a college freshman in 1960. She continued working for Emma, who was then assistant registrar, throughout college, even during the summers. Following graduation, Carlyon left Missoula, returning several years later, married and expecting her second baby. She wanted to work on campus, in the registrar’s office, if possible. Emma interviewed her for a secretarial position posted by Registrar Leo Smith. She told Carlyon that Leo wouldn’t hire her because she was pregnant. “I’ll hire you,” Emma said and she did. Carlyon was soon back on staff and still is today. “Emma always appreciated a hard worker,” she says, “and she never fired anyone. If someone was not up to par, they just knew it. They went away. Emma had a way of getting them to leave. She never raised her voice. She was always a lady.” Carlyon doesn’t remember Emma ever taking a coffee break either. “People always came over to see her,” she recalls. “She couldn’t leave.”

Ruth Rollins Brocklebank ’67 keeps handy a poem Emma gave her forty years ago when she worked for Emma in the registrar’s office. “It typifies her view about life and work,” Ruth believes:

A horse can’t pull while kicking

This fact we merely mention,

And he can’t kick while pulling,

Which is our chief contention.

Let’s imitate the good horse

And lead a life that’s fitting;

Just pull an honest load, and then

There’ll be no time for kicking.

“Mrs. L. is amazing,” Brocklebank says. “She remains interested in life—is a great advocate for education—encourages people to improve. She has been a source of inspiration for me since my meeting her.”

Karen Smith Temple, currently an internal auditor at UM, received many life lessons from Emma when she worked for her in the 1970s. “Emma was one of the first people to see the importance of a woman keeping her identity, of not being Mrs. John Doe, but of being Mrs. Jane Doe,” Temple says. She still thanks Emma for showing her how to write a letter of introduction she would use later when job searching in a new state. Emma’s sage advice, “It’s important to introduce yourself,” has stayed with Temple throughout the years. She fondly remembers a gift of plum trees from Emma’s yard when she and her husband needed help with landscaping. “I don’t know how she knew we needed trees,” Temple muses. “Emma just knew.”

Emma lives in a beautifully furnished third-floor apartment at the Village Senior Residence near Fort Missoula. She paid rent for a year before she could move in to make sure she got the spot. “It’s the farthest walk from the elevators and stairs,” she explains. “ I have a view of Mount Jumbo every day, and when the trees are bare, I can see Mount Sentinel.” Baskets of letters hug the end of her couch, bundled according to their arrival at Christmas, her birthday, or Mother’s Day. Although she has no children of her own, countless University “children” send her greetings on many occasion. She answers them all. In her spare bedroom is a computer. Emma has discovered e-mail.

An autographed photo is taped to a kitchen cupboard door. “To the best lookin’ gal in the building! With love, Monte,” it proclaims. A bobblehead Monte stands nearby. A large stuffed bear greets visitors in Emma’s entryway. Her University and Grizzly ties are reflected in the many awards, photographs, and plaques on her walls. Emma is happy about Don Read returning to campus, and that “her” boys—Krysko and Tinkle—will be coaching basketball this winter. “Until two years ago I’d attended all Griz and Lady Griz basketball games,” Emma says. “I was the oldest attendee at all the Griz football games, too.” Last season Emma missed three Griz football games. She’d been out walking, fell, and broke her hip. Her recovery was quick and complete, but she’s given up her Griz football tickets this year and will watch the games on TV.

“I don’t want to be a burden to anyone,” she says, and doesn’t understand, “what all the fuss is about.” Quick to credit others and deflect attention from herself, she still worries that “I just might do something that would make me not be the same woman walking out of a room that I was walking into it.”

That’s not yet happened. Most likely it won’t. When Emma Lommasson leaves a room, or a building, or an institution she leaves it a better place. And most often someone seeing her leave will openly admit, “I want to be just like her when I’m her age” (really meaning “just like her, right now!”).

“I’ve known all but the first four University presidents, Emma Lommasson quietly states. “There’s no one else who can say this.”

Betsy Brown Holmquist ’67, M.A. ’83, is a writer/editor for the UM Alumni Association She has known Emma Lommasson since her undergraduate years at UM and admits to wanting to be like Emma, too.

Betsy Brown Holmquist ’67, M.A. ’83, is a writer/editor for the UM Alumni Association She has known Emma Lommasson since her undergraduate years at UM and admits to wanting to be like Emma, too.