Invest in Discovery

THE SAGE GROUSE AND WEST NILE:

UNRAVELING THE MYSTERY, FINDING A REMEDY

Male sage grouse are the strutting dandies of Montana’s eastern prairies. During mating season they inflate large air sacks hidden beneath their brilliant white chest feathers to impress females and warn away lesser males, then release the air with distinctive popping noises.

Male sage grouse are the strutting dandies of Montana’s eastern prairies. During mating season they inflate large air sacks hidden beneath their brilliant white chest feathers to impress females and warn away lesser males, then release the air with distinctive popping noises.

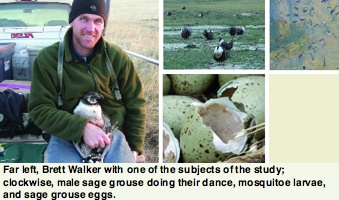

Doctoral student Brett Walker was surprised to find one of these spectacular creatures dying in July 2003 while working on a UM College of Forestry and Conservation sage grouse study. Fifteen minutes after he found the bird, it died.

What killed it? Walker worried that it might be West Nile virus because 227 bird species have been identified as carriers of the potentially deadly illness. So he and his instructor, UM wildlife biology Professor Dave Naugle, had the bird tested by the Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory. Sure enough, West Nile was the culprit.

That first bird was only the beginning. During the remainder of 2003, 25 percent of all radio-collared sage hens in Naugle’s study died as a result of the virus and another 10 percent died in 2004.

|

The UM Foundation encourages contributions for individual research projects and programs at the University. To learn how you can help, contact:

Lisa Lenard, director of development and alumni relations for the College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana Foundation, P.O. Box 7159, Missoula, Montana 59807-7159; (800) 443-2593 or (406) 243-5533; lisa.lenard@mso.umt.edu. |

||

Sage grouse definitely don’t need more stress in their lives. Previously widespread, they no longer exist in half of their original range in North America; recently they narrowly missed listing under the Endangered Species Act. Most of their decline is linked to loss of sagebrush habitat caused by human encroachment. Two remaining strongholds for the birds are southeast Montana and northeast Wyoming.

Naugle’s research was funded by the Bureau of Land Management two years ago to explore a potential threat to the grouse: booming coalbed natural gas development on their Montana and Wyoming range.With a new type of energy development and West Nile appearing at roughly the same time, Naugle’s team wanted to know if the two might be linked.

Coalbed methane production brings millions of gallons of groundwater to the surface along with natural gas, and the water is then stored in large ponds. Naugle’s group learned these ponds provide excellent breeding grounds for Culex tarsalis mosquitoes—which happen to feed primarily on birds and therefore are a major host for West Nile. Sage grouse are at risk because their females and young congregate around water, where food is plentiful in late summer.

Naugle says researchers are now partnering with industry to build ponds that are less conducive to mosquito production and the spread of West Nile. Future studies of the host dynamics of West Nile may bring Naugle and his staff closer to protecting sage grouse ... and possibly us.

Naugle says the work his team does wouldn’t be possible without help from the UM Foundation, which channeled research funding from the Wolf Creek Charitable Foundation and the Exxon Mobil Foundation to his field work. Wolf Creek helped purchase trucks to shuttle scientists around rugged sage grouse habitat, and Exxon helped with general research expenditures.

“The Foundation’s expertise and flexibility allowed us to move money quickly so we could focus on the research question at hand,” Naugle says.

John Scibek, director of planned giving at the UM Foundation, was instrumental in ensuring the funding made it to scientists in the field. “I’ve found the caliber of science at UM makes it easier to link our researchers with funding sources eager to help out,” he says.

![]()

![]()