Pharmacy Rising

A Science to Success Story

by Chad Dundas

When Professor Rich Bridges came to UM almost twelve years ago, the University's sagging pharmacy school didn't have the equipment needed to outfit his state-of-the-art neuroscience laboratory. It certainly didn't have the money to buy the expensive gadgets Bridges needed to continue his research into the human brain. With just a dozen faculty members and only ninety students, the pharmacy school ranked near the bottom of similar institutions nationwide. Though Bridges himself is reluctant to say the school was struggling, some reports indicate that a few years earlier it was at risk of losing its accreditation.

When Professor Rich Bridges came to UM almost twelve years ago, the University's sagging pharmacy school didn't have the equipment needed to outfit his state-of-the-art neuroscience laboratory. It certainly didn't have the money to buy the expensive gadgets Bridges needed to continue his research into the human brain. With just a dozen faculty members and only ninety students, the pharmacy school ranked near the bottom of similar institutions nationwide. Though Bridges himself is reluctant to say the school was struggling, some reports indicate that a few years earlier it was at risk of losing its accreditation.

Lab space was adequate, but funding for equipment was nearly nonexistent. Bridges says he remembers how the new dean, Dave Forbes, and Vernon Grund, pharmacy professor and chair of the then-fledgling Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, had to "piece together a start-up package" for his lab. Luckily, the Division of Biological Sciences was more than willing to help out. And support for Bridges came from several labs in UM's biology and chemistry departments, as well as labs in the pharmacy school.

Grund remembers that biochemistry Professor Walter Hill donated at least one expensive and vital piece of equipment from his own lab to get Bridges up and running. Hill said he would do without until Bridges' lab could buy its own. Bridges says that it was seeing generosity like Hill's--done for the overall good of science on campus--that convinced him that coming to UM would be the right thing to do.

"The number of different groups that chipped in from outside of pharmacy and put equipment into my lab so I could do my experiments, I was blown away by that," Bridges says. "That never would have happened at a medical school, not in a million years."

Bridges now directs UM's Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience. And those lean times are just distant memories for folks involved with the pharmacy program today. The hiring of Bridges in 1993 signaled a bold and innovative new direction for the school. From the time Forbes and Grund took over the administration in the early '90s, they were on a mission to prove that, by focusing on research and recruiting leading scientists like Bridges, UM's pharmacy school could rebound and emerge as a leader in the field. The results have been nothing short of miraculous.

Bridges now directs UM's Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience. And those lean times are just distant memories for folks involved with the pharmacy program today. The hiring of Bridges in 1993 signaled a bold and innovative new direction for the school. From the time Forbes and Grund took over the administration in the early '90s, they were on a mission to prove that, by focusing on research and recruiting leading scientists like Bridges, UM's pharmacy school could rebound and emerge as a leader in the field. The results have been nothing short of miraculous.

"I think (the previous administration of the pharmacy school) didn't see the importance or the role that research could play," Bridges says, "so it wasn't a priority for the faculty ... it's not surprising that not much grew. I came in after the philosophical decision had been made that research was important and a good thing to do."

In a little more than a decade the school has become UM's top-funded unit and is now ranked fifth in the nation among ninety-two pharmacy schools in total research funding. And that, notes Dean Forbes, is for a school in a state without a medical school--the only one without a medical school in the top twenty institutions receiving the grants.

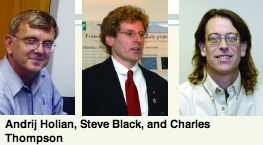

Pharmacy professors have a wealth of high-profile grants from the National Institutes of Health and account for three of the University's top five grant-earning faculty members--Andrij Holian, Charles Thompson, and Steve Black. The other two in the top five are Lloyd Queen, School of Forestry and Conservation, and Richard van den Pol, Division of Educational Research and Service.

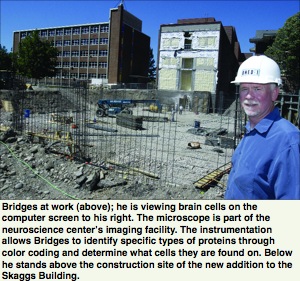

With the burgeoning research, the pharmacy school has already outgrown the Skaggs Building, completed in 1999. A nearly 60,000-square-foot addition to the building is under construction, to go along with the new bioresearch facility, which opened last August at the south end of campus. (See story on page 4.)

"It has far exceeded [in the past ten years] where I thought it would be in my lifetime," Bridges says of the school's success. "It's just amazing. Very, very exciting. I think it's paved the way for new construction, new educational opportunities for students, new research opportunities for students, new graduate programs--they've all been tied in to the concept of improving research."

"It has far exceeded [in the past ten years] where I thought it would be in my lifetime," Bridges says of the school's success. "It's just amazing. Very, very exciting. I think it's paved the way for new construction, new educational opportunities for students, new research opportunities for students, new graduate programs--they've all been tied in to the concept of improving research."

Bridges, whose research centers on ways of preventing common killers such as stroke, seizure, Alzheimer's, and Lou Gehrig's disease, has been a stalwart throughout the growth process. He helped build the Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience from scratch, where he and his research team study how the brain uses molecular transporters to regulate the nervous system.

In the past two years, the faculty of the Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE), which includes the neuroscience center, has grown from four to nineteen. Recently Bridges received word that an initial $10 million COBRE grant used to develop the neuroscience center has been renewed at approximately the same amount. The renewal, which is usually more difficult to obtain than the original start-up money, Bridges says, means that UM is on the right track. Still, Bridges says the school can continue to grow and improve.

"Essentially it's bringing about, on this campus, a culture change for people to realize that we can do nationally competitive biomedical research at The University of Montana," Bridges says. "That's still a pretty new concept."

The fact that a small university like UM has seen so much initial success in its fairly new commitment to research can be attributed to an atmosphere of cooperation that extends through all the sciences on campus, Bridges says. The lab team in the neuroscience center often seeks help from workers in other disciplines such as chemistry, biology, and mathematics and even lends a hand when it comes to trying to recruit new faculty into other departments. Bridges says that feeling of community and teamwork is one of the things that sets UM apart from other, larger institutions.

"There were so few scientists here that there was a survivorship mentality," Bridges says. "The centers and the graduate programs have been very good at breaking down the departmental barriers. Students and faculty are brought together based on what they study, not where they get their mail."

Having no medical school at UM is not necessarily a detriment, Bridges says, adding that many faculty members in the basic sciences feel like they have more influence over the direction of the pharmacy program and the research being done on campus than if there was a medical school.

"Quite often faculty who have basic research interests in the medical sciences tend not to play as much of a role in shaping policy at a medical school as those that are running clinical projects," Bridges says. "We've recruited a number of people from medical schools--large medical schools--who have come here because they see the potential to do something different, to do science the way they would like to do it."

UM scientists work closely with clinicians and St. Patrick Hospital. Bridges' neuroscience center often does research with the hospital's Montana Neuroscience Institute as part of a three-pronged cooperative effort between the University and the hospital that also includes new institutes dedicated to the study of the heart and cancer. Collaborating with the hospital puts UM's focus on what the school terms "translational research," or what Grund calls "bench to bedside" science. Simply put, it means that university scientists work with the hospital to develop research with real clinical applications.

Aside from the hospital, UM also has worked closely with Montana State University to create the new neuroscience program, directed by neuroscientist Diana Lurie. The program enrolled its first students last fall. The two schools, old rivals in other areas, progressed hand-in-hand throughout the five-year planning process to get approval from the state Board of Regents for the new program. Now the universities teach some of the courses together, using high-end video teleconferencing to link Bozeman and Missoula for certain lectures.

With three Ph.D. programs now available, where ten years ago there were none, a faculty that has tripled in size, and an enrollment that continues to swell, it can be argued that the pharmacy school is now the most dynamic and flourishing school on campus. It is certainly the most lucrative. Even the architects of the new programs admit they're stunned by the school's success.

"If you asked me thirteen years ago I wouldn't have believed it," Grund says. "As a matter of fact, as I visit some of my colleagues around the country, they can't believe it either."

Bridges says he's excited about the future of the program, hoping to get faculty from the physics department on board with research in the neuroscience center soon. He says he sees no reason the school can't continue to thrive, as long as the campus stays open to the spirit of cooperation that's already earned it a reputation as one of the best in the nation.

"We still have a long way to come," Bridges says. "We're still very small and I think it's important for us not to lose sight of the key things that were important to us while building the program and to continue to work using those themes because so far it's worked really, really well."

The Brain Behind the Bucks

Pharmacy's Researchers

by Chad Dundas

In a little more than ten years, funding for the pharmacy school has gone from $587,000 to more than $14 million. Here's a look at some of the dedicated scientists who've built the program into a national gem.

In a little more than ten years, funding for the pharmacy school has gone from $587,000 to more than $14 million. Here's a look at some of the dedicated scientists who've built the program into a national gem.

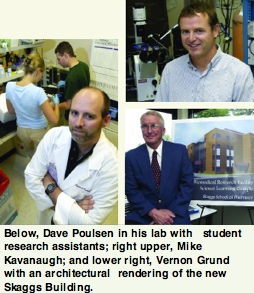

Vernon Grund came to UM thirteen years ago from the University of Cincinnati to serve as the chair of the Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Working with Dean Forbes, Grund has been instrumental in hiring the faculty and constructing the facilities that have turned the school around. Grund's own work focuses on cardiovascular disease and diabetes with an emphasis on atherosclerosis.

The pharmacy school boasts three of UM's top five grant recipients from 2004, and Andrij Holian is the University's No. 1 earner at $5.06 million. Holian, director of the Center for Environmental Health Sciences, works primarily in the study of lung injury and disease. His research focuses on the effects of outside agents like asbestos and smoke on the lungs and also on developing new ways to identify individuals who may be predisposed to developing serious diseases.

One of the University's top researchers will be leaving after fall semester. Steve Black came to UM in 2004 from Northwestern University with five NIH grants worth about $5 million and picked up a prestigious LaDuke Foundation grant worth about $6 million in 2005. He studies the inner workings of blood vessels, with the goal of combating health problems such as high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and other blood-system ailments. When we went to press he had decided to pursue his research at the Medical College of Georgia in Atlanta.

One of the University's top researchers will be leaving after fall semester. Steve Black came to UM in 2004 from Northwestern University with five NIH grants worth about $5 million and picked up a prestigious LaDuke Foundation grant worth about $6 million in 2005. He studies the inner workings of blood vessels, with the goal of combating health problems such as high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and other blood-system ailments. When we went to press he had decided to pursue his research at the Medical College of Georgia in Atlanta.

Professor Michael Kavanaugh, the associate director of UM's COBRE Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience, came to Montana in January 2003 from the Oregon Health and Science University's prestigious Vollum Institute. A graduate of Washington University in St. Louis with a doctorate in biochemistry from OHSU, Kavanaugh's work at UM focuses, like Rich Bridges', on neurotransmitter transporters. Kavanaugh's lab studies how the transporters regulate function in the central nervous system.

Charles Thompson, professor of medicinal chemistry, was third on the list of UM's top grant earners in 2004 and came to UM from Loyola University in Chicago after studying at Harvard. Thompson brought in $3.6 million to aid his Thompson Research Group (Web site: http://www2.umt.edu/medchem/) in bio-organic, medicinal, and synthetic organic chemistry with an emphasis in neuroscience.

Since joining UM and the Montana Neuroscience Institute as a research assistant in 1997, Professor Dave Poulsen has worked as a translational research scientist at St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center. Poulsen studies gene therapy and how it can be used to treat neurological disorders such as epilepsy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), chronic pain, and spinal cord injury. Poulsen's research also addresses ways of treating hearing loss through the regeneration of tiny hairs inside the inner ear and ways of treating the pain of bone cancer without morphine, using the body's natural opiates.

In just ten years, research funding at UM has increased from $20 million in 1994 to $65.7 million in 2004. This year, University President George Dennison has challenged the entire faculty to drive the total to more than $70 million. The pharmacy school is leading the way.

Chad Dundas '02 has worked as a reporter for the Associated Press, Missoulian, and the Missoula Independent. He is pursuing an M.F.A. in fiction at UM. His first short stories will be published this fall in literary journals of Purdue University and the University of Southern Illinois-Edwardsville.

Chad Dundas '02 has worked as a reporter for the Associated Press, Missoulian, and the Missoula Independent. He is pursuing an M.F.A. in fiction at UM. His first short stories will be published this fall in literary journals of Purdue University and the University of Southern Illinois-Edwardsville.