Nancy and her Wild Kingdom

A profile of a woman and her art: a life where the two are not easily separated.

by Megan McNamer “One day in the summer of 2000 Nancy Erickson was working in her Pattee Canyon studio making small drawings of cougars. It was a season that felt epic in its conflux of drought, heat, and fire. Erickson herself was feeling ill from the effects of treatment for thyroid cancer. She looked up from the cougar she was drawing and out at the surrounding woodlands. There was a real cougar, looking at her. They held each other's gaze.

“One day in the summer of 2000 Nancy Erickson was working in her Pattee Canyon studio making small drawings of cougars. It was a season that felt epic in its conflux of drought, heat, and fire. Erickson herself was feeling ill from the effects of treatment for thyroid cancer. She looked up from the cougar she was drawing and out at the surrounding woodlands. There was a real cougar, looking at her. They held each other's gaze.

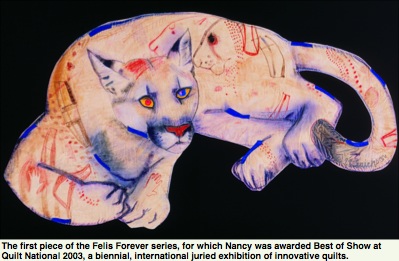

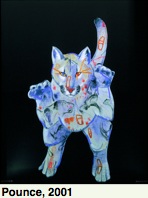

Walter Benjamin wrote that to perceive the aura of a phenomenon is to invest it with the capacity to look at us in turn. Erickson's Felis Forever series is especially "auratic." It is a collection of big free-form fabric cats incorporating paint, oil sticks, and charcoal with machine stitching and applique. The cats are poised and regal, as cats will be. These cougars have been transformed into art, though, and they look like they know it. Somehow, they appear to be active agents in the process. Their bodies are imprinted all over with bits and pieces of other animals--horses, gazelle-like creatures, a tiny rhino. The cats wear their altered beauty like jackets or robes, ceremonial and purposeful. They are conscious of an audience.

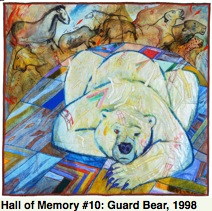

Of the Felis Forever series, Erickson writes: In the mid-1990s I worked on quilted pieces that showed bears in caverns or in rooms formerly occupied by humans and covered with cave drawings of early animals. The bears wander through these environments, teaching their cubs about history. In this new series ... the ancient history is imprinted on the cougars; the cougars are freed of caves and rooms, and they move freely on the wall.

The mutual regard between Erickson's big cats and their contemplators keeps these images loose and moving, their meaning unfixed. Are the marks on these bodies accidents of history or collected messages? Are they scars, brands, or adornments? Some of the images hint at the human world. Yellow highway lines mark a haunch, red dots cluster on a brow like a rash or newsprint.

Some of the cats have mismatched eyes: one iris is crimson, the other cobalt blue, both set in a golden glow. The effect is not skewed so much as kaleidoscopic. Fear flickers with resignation, suffering with comfort, anger with benevolence. It is as if one eye has seen something we have not yet seen. The other eye gazes at us--we, who are still mostly in the dark--with something like compassion.

Artists are like these cats. They see with two kinds of eyes.

Of the Felis Forever series, Erickson writes: In the mid-1990s I worked on quilted pieces that showed bears in caverns or in rooms formerly occupied by humans and covered with cave drawings of early animals. The bears wander through these environments, teaching their cubs about history. In this new series ... the ancient history is imprinted on the cougars; the cougars are freed of caves and rooms, and they move freely on the wall.

The mutual regard between Erickson's big cats and their contemplators keeps these images loose and moving, their meaning unfixed. Are the marks on these bodies accidents of history or collected messages? Are they scars, brands, or adornments? Some of the images hint at the human world. Yellow highway lines mark a haunch, red dots cluster on a brow like a rash or newsprint.

Some of the cats have mismatched eyes: one iris is crimson, the other cobalt blue, both set in a golden glow. The effect is not skewed so much as kaleidoscopic. Fear flickers with resignation, suffering with comfort, anger with benevolence. It is as if one eye has seen something we have not yet seen. The other eye gazes at us--we, who are still mostly in the dark--with something like compassion.

Artists are like these cats. They see with two kinds of eyes.

Nancy Erickson's artist statements invoke the words that Chief Seattle reportedly spoke in 1854: "What good is man without the beasts? If all the beasts were gone, man would die from a great loneliness of spirit. For whatever happens to the beasts, soon happens to man. All things are connected."

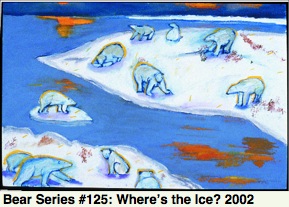

Erickson's vision is apocalyptic, but also peaceful; catastrophic, yet redemptive; both angry and playful. In one piece, bears embrace; in the next their necks stretch up toward missiles flying overhead. These wild animals are juxtaposed with chairs and electrical sockets.

Her art is not neatly categorized. Although she grew up on a ranch outside of Livingston and studied zoology as an undergraduate, she is not showing us in her art what animals look like. ("I'm a [Charlie] Russell reject," she laughs, referring to an unsuccessful submission to the Russell Museum's annual art auction in Great Falls.) Neither is she educating us, necessarily, about the specifics of animal lives. Instead, each of her works brings forth a being "such as never was before and will never come to be again" (Heidegger: The Origin of the Work of Art). A quietude hovers over all this. Her artistic impulse, she says, is "to dispel the sadness."

Nancy Erickson's artist statements invoke the words that Chief Seattle reportedly spoke in 1854: "What good is man without the beasts? If all the beasts were gone, man would die from a great loneliness of spirit. For whatever happens to the beasts, soon happens to man. All things are connected."

Erickson's vision is apocalyptic, but also peaceful; catastrophic, yet redemptive; both angry and playful. In one piece, bears embrace; in the next their necks stretch up toward missiles flying overhead. These wild animals are juxtaposed with chairs and electrical sockets.

Her art is not neatly categorized. Although she grew up on a ranch outside of Livingston and studied zoology as an undergraduate, she is not showing us in her art what animals look like. ("I'm a [Charlie] Russell reject," she laughs, referring to an unsuccessful submission to the Russell Museum's annual art auction in Great Falls.) Neither is she educating us, necessarily, about the specifics of animal lives. Instead, each of her works brings forth a being "such as never was before and will never come to be again" (Heidegger: The Origin of the Work of Art). A quietude hovers over all this. Her artistic impulse, she says, is "to dispel the sadness."

When Erickson obtained her M.F.A. in painting from UM in 1969 she went right from studying art to making it and she hasn't let up since. She has shown her work in some 500 exhibitions from 1965 to the present, all over the world, and it is included in a number of permanent collections, including the Seattle Art Museum, the American Craft Museum in New York, the Holter Museum in Helena, the Missoula Art Museum, and UM's Montana Museum of Art and Culture. The sheer effort--both emotional and physical--that must go into such prolific production is daunting.

"She is a major figure in the world of art quilts, and yet she is also deeply committed to the local community. We are lucky to have her here," says renowned ceramicist Beth Lo, a UM art professor and fellow member of the Pattee Creek Ladies Salon. The group of women artists meets bi-weekly at Erickson's studio. "I've been a member of the Salon for probably fifteen years, and it is a wonderful group to be involved with," Lo says. "We draw, celebrate the female figure, and talk! We talk about art, women's issues, local and global politics, health, families, our worries and our personal victories, our favorite movies, books, and food. Nancy's personality sets the tone. She has the ability to connect with many people, remembering what each and every one is up to, and she keeps contact with little notes and gifts."

When Erickson obtained her M.F.A. in painting from UM in 1969 she went right from studying art to making it and she hasn't let up since. She has shown her work in some 500 exhibitions from 1965 to the present, all over the world, and it is included in a number of permanent collections, including the Seattle Art Museum, the American Craft Museum in New York, the Holter Museum in Helena, the Missoula Art Museum, and UM's Montana Museum of Art and Culture. The sheer effort--both emotional and physical--that must go into such prolific production is daunting.

"She is a major figure in the world of art quilts, and yet she is also deeply committed to the local community. We are lucky to have her here," says renowned ceramicist Beth Lo, a UM art professor and fellow member of the Pattee Creek Ladies Salon. The group of women artists meets bi-weekly at Erickson's studio. "I've been a member of the Salon for probably fifteen years, and it is a wonderful group to be involved with," Lo says. "We draw, celebrate the female figure, and talk! We talk about art, women's issues, local and global politics, health, families, our worries and our personal victories, our favorite movies, books, and food. Nancy's personality sets the tone. She has the ability to connect with many people, remembering what each and every one is up to, and she keeps contact with little notes and gifts."

Erickson "got to art" only after earning a bachelor's degree in zoology and an M.S. in foods and nutrition from the University of Iowa. By that time she was in her thirties and Erickson says, "I was hungry for it." A visitor to her house will notice that she has painted her refrigerator a cobalt blue, the same color as her arctic skies and cougar eyes--a statement of ... what? The delight of the unexpected? Art out-of-bounds? The domesticity of the wild?

In fact, her daughter had painted the kitchen cabinets with a forest scene, so she decided the refrigerator needed painting, too. It features a tree rendered in phosphorescent paint so that it glows in the dark. The same blue swirls through a large, abstract painting in the living room. The eye latches onto an ordinary goose-necked lamp down in the corner of the canvas, a lamp you might buy at Target.

Erickson "got to art" only after earning a bachelor's degree in zoology and an M.S. in foods and nutrition from the University of Iowa. By that time she was in her thirties and Erickson says, "I was hungry for it." A visitor to her house will notice that she has painted her refrigerator a cobalt blue, the same color as her arctic skies and cougar eyes--a statement of ... what? The delight of the unexpected? Art out-of-bounds? The domesticity of the wild?

In fact, her daughter had painted the kitchen cabinets with a forest scene, so she decided the refrigerator needed painting, too. It features a tree rendered in phosphorescent paint so that it glows in the dark. The same blue swirls through a large, abstract painting in the living room. The eye latches onto an ordinary goose-necked lamp down in the corner of the canvas, a lamp you might buy at Target.

Erickson is seventy this year and appears as fit as a lean teenager. She jogs two and a half miles a day and works out for thirty minutes. She is interested in diet. The safeguarding of her health, perhaps especially after the precarious period five years ago, seems to be part of her work as an artist and her concerns--endangerment, protection, needs, both large and small. One of her bear pieces alludes to a back rub.

Erickson likes aesthetic oddities, and she is an advocate for the circuitous route. She and her husband, Ron Erickson, a former UM chemistry professor and Montana state legislator, have two daughters who found their own right paths in middle age. Of her art, Erickson says she is always seeking to make it new. "I have to re-create myself."

Erickson is seventy this year and appears as fit as a lean teenager. She jogs two and a half miles a day and works out for thirty minutes. She is interested in diet. The safeguarding of her health, perhaps especially after the precarious period five years ago, seems to be part of her work as an artist and her concerns--endangerment, protection, needs, both large and small. One of her bear pieces alludes to a back rub.

Erickson likes aesthetic oddities, and she is an advocate for the circuitous route. She and her husband, Ron Erickson, a former UM chemistry professor and Montana state legislator, have two daughters who found their own right paths in middle age. Of her art, Erickson says she is always seeking to make it new. "I have to re-create myself."

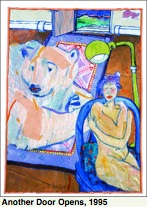

The Toklat wolves in her studio might be up to the same thing. In the summer of 2005, Erickson's studio contains four large drawings of wolves standing like guardians over the tables laden with paint and tools and other shop gear needed for such labor-intensive work. The wolves will join those who already are in her Toklat Wolf Series, large quilted pieces akin to the bears and the cats, made from velvet, satin and cottons, paints, oil sticks, ball point pen, machine stitching, applique.... The inspiration for these wolves came from Erickson's reading about the Toklat wolves that were killed after leaving the boundaries of Denali Park. This series thus far seems a step closer to the human world, for better or worse. The imprintings have become, in part, inscriptions. The letter "K" in the middle of the forehead of "Precious," an already-completed cousin of the paper wolves in the studio, looks distinctly like a brand and not necessarily one borne by an animal. But a closer look reveals that the "K" belongs to the word "Toklat." The broad stripe of white and bits of black around the wolf's eyes begin to look like gang colors. Small scrawls of more words emerge: Toklat, pack, Toklat.... These words look almost like tattoos. Or are they graffiti? Erickson's creative fixation with animals of the far north began with the bears for which she is perhaps best known. Interestingly, her polar bear imaginings were first sparked from looking at photos in Life magazine when she was a child. Erickson's work may be seen as a way of joining the wild with the domestic, making a complicated world more comfortable. But the odd domestic settings, paradoxically, help these bears retain their strangeness. In many of Erickson's paintings, contemplative nudes share space with animals. They bring to mind the cool twilight novel Bear by Marian Engel, about the joining of the spirits and bodies of a bear and a woman. These human forms don't look back at us, or if they do, it is over one shoulder, obliquely. They look sideways off the canvas in a detached way, as if they are daydreaming about the animals next to them, or they curl up in self-protective poses, their backs turned, only faintly aware of destiny and fate, hope, health, and fragility.

Megan McNamer's '76 varied career includes teaching ethnomusicology at UM and writing about Hi-Line basketball for Sports Illustrated. She currently is the administrator for the Missoula Writing Collaborative, a writers-in-the-schools program in western Montana.

Megan McNamer's '76 varied career includes teaching ethnomusicology at UM and writing about Hi-Line basketball for Sports Illustrated. She currently is the administrator for the Missoula Writing Collaborative, a writers-in-the-schools program in western Montana.