Here's the Beef

Story and Photos by Ari LeVauxUM's Farm to College program links Montana producers with campus consumers.

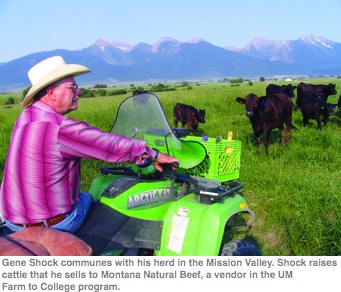

Gene Shock sits on his green four-wheeler, gazing over his pasture toward the Mission Mountains. I’m a few feet away, surrounded by a ring of Shock’s cows, who are intently gazing at me. One cow gets in my face and sniffs. “That’s Mary,” says Shock, who says he’ll hang on to her and breed her next year. “Her half sisters and brothers are what go to Montana Natural Beef.”

Last year, Montana Natural Beef, a Ronan-based company that markets beef raised in the Mission Valley, sold roughly $37,000 of that beef to UM.

It may seem a no-brainer that Montana beef, among the world’s finest, is fed to Montana’s students. But today’s cattle industry, like many other food industries, operates on a scale bigger than Big Sky Country. The beef could come from anywhere. The distributor might say it is from Idaho. But that only means the cows were slaughtered there, perhaps fattened on an Idaho feedlot. Or they could have been raised in Florida, Texas, Washington, or Montana and fattened in Colorado or Kansas, “It’s a mixed bag,” says David Opitz, purchasing manager for University Dining Services (UDS). “Unless I can source my meat exactly, I don’t try to guess. You just never know.”

UM’s Farm to College (FTC) program has eliminated a bit of that guessing by taking the mystery out of the meat. “It started with a conversation after a campus recycling oversight committee meeting,” explains UDS Director Mark LoParco. “Professor Hassanein [assistant professor in UM’s Environmental Studies Program] asked me what I thought about serving local foods. That’s something I’ve wanted to get going for some time, but didn’t have the resources [for]. After that meeting, she lined up four graduate students and off we went.”

The group met regularly during the spring of 2003 to discuss the possibilities of local foods on campus. They researched what other schools were doing and what local foods were available in the quantities that UDS required.

These inquiries culminated in a festive breakfast event called Montana Mornings. Menus were printed, with detailed descriptions of the origins of all ingredients. Eggs from Moiese were cooked into omelets, stuffed with shitake mushrooms from Ninemile, shallots and cheese from the Bitterroot, and salsa from Belgrade. Cider syrup from Bitterroot apples was poured over Cream of the West hot cereal, made in Harlowton. Waffles from Scobey, bacon and potatoes from Kalispell, and beef from Ronan were on the menu as well.

Besides a publicity event, Montana Mornings was a market test, an attempt to assess student interest in local food. The response, based on an exit survey, was very positive. Most breakfast eaters said they would choose local food on a regular basis if they could. Encouraged, FTC rolled forward.

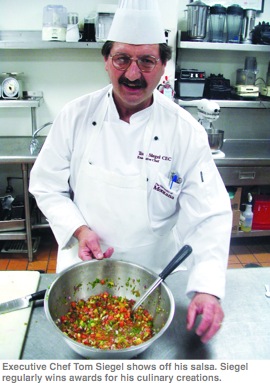

Three years and more than $1.2 million later, the program’s purchases exceed 13 percent of the UDS annual food budget. “Farm to College has become standard operating procedure,” says UDS Executive Chef Tom Siegel. “At first, finding new vendors was this big effort. Now we have our inroads laid. We know our vendors. We’ve made the leap; it’s not new anymore. It’s the way we do business.”

UM’s FTC program has been featured in articles in Time, the New York Times, and many more publications closer to home. This national attention puts UM on a short list of innovative universities with FTC programs that includes Brown, Yale, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, Williams, and Middlebury.

One would expect a different spin on the FTC menu for the various regions. Goat cheese and figs on the California salads, perhaps, while the East Coast schools have the agricultural and cultural resources to turn out a pretty good pizza. Here in Montana we have the ingredients to construct perhaps the epitome of the American college culinary experience: the burger.

A Hamburger & Fries, Please

There may be no better meal than the hamburger with which to illustrate the many tendrils that the FTC program has spawned.

To be clear, we’re talking about the classic hamburger meal, served on a bun, with a pickle, tomato, lettuce, and onion, all next to a pile of fries. Everything in this meal could be grown or made in Montana, including extras like cheese, bacon, mushrooms, and condiments—catsup, mustard, and mayo.

Many of the ingredients in a typical UM hamburger meal already come from Montana producers, including the Montana Natural Beef burger. That company requires that any beef it purchases be antibiotic- and hormone-free.

UDS did an experiment in which “mixed bag” hamburger patties—purchased on the open market through SYSCO, UM’s primary vendor—were compared to the more expensive Montana Natural Beef burgers. Equal quantities were cooked side by side, then weighed again. They discovered that after cooking off the water, the Montana Natural Beef burger weighed more than the SYSCO patty. This difference in water content all but erased the difference in price per pound at the front end.

Besides that extra water, it’s possible that the mixed bag beef contains other substances that don’t cook off so easily. Every day, an average 200,000 Americans suffer food poisoning; 900 are hospitalized, and 14 die. Contaminated meat is the largest vector of food poisoning. According to a USDA study, 78 percent of ground beef contains microbes that are spread primarily in fecal matter. “You gotta be careful with hamburger,” agrees Will Tusick of Montana Natural Beef. “It’s the proverbial canary in the coal mine. Everything’s gotta be just right, and if there is any contamination in the meat it will show up in the burger. In those giant mega-facilities, they mix a bunch of different stuff together. There could be 100 different cows in one patty.”

Montana Natural Beef cows are processed at USDA-inspected Rocky Mountain Gourmet Steaks in Missoula, which earns thousands of dollars a year by turning Montana Natural Beef into hamburger, keeping those dollars in the local economy.

Shock is proud of his product, proud that UDS appreciates the quality of his cattle and is willing to pay above-market prices for it. He adds that there is no cut of meat he wouldn’t grind into hamburger. “I might be a little unusual in that department,” he admits.

Hormones can increase a steer’s weight by as much as fifty pounds. Shock prefers a more old fashioned way to get big cows. His cattle are a mix of breeds—Brown Swiss—the breed he favored when he was a dairy farmer—and Black Angus, preferred by the market for its marbling. “The Brown Swiss in them gives the mothers lots of good milk, which helps them grow so big,” he says.

Anyone who’s spent time on a college campus can attest that there are more than enough hormones acting on students’ bodies without hormones in the meat. Marya Bruning, the UDS registered dietician, agrees. “No hormones or antibiotics is definitely positive for long-term health,” she says. Elsewhere, Bruning sees FTC making dietary improvements as well. “The whole wheat bun option that we get from Wheat Montana is wonderful. Whole grain and added fiber have huge benefits.” She notes the fresh produce that goes on the burger has more vitamins because it’s fresher and phytochemicals like lycopene and lutein are better preserved in fresh tomatoes.

“And just as important,” she says, “people can’t be healthy if their environment isn’t healthy. Bringing food from closer to home means less shipping, which means cleaner air, water, and soil. And buying local builds healthier social networks. Health is about more than just what we eat.”

Where the Cilantro Meets the Salsa

Nancy Cohen, chef de partie for campus catering, prowls the kitchen with a silent authority. She’s supervising the baking of several pans of brownie-like goodness when Amanda Behrens arrives, pulling a cart piled high with produce boxes. Cohen turns around to greet her. “Lemme see the cilantro,” she says. “Is it clean?” Without waiting for a reply, Cohen digs into a box, finds the cilantro, and grunts an approval. The kitchen relaxes back into business as usual, chopping and shuffling.

Nancy Cohen, chef de partie for campus catering, prowls the kitchen with a silent authority. She’s supervising the baking of several pans of brownie-like goodness when Amanda Behrens arrives, pulling a cart piled high with produce boxes. Cohen turns around to greet her. “Lemme see the cilantro,” she says. “Is it clean?” Without waiting for a reply, Cohen digs into a box, finds the cilantro, and grunts an approval. The kitchen relaxes back into business as usual, chopping and shuffling.

Behrens is the delivery driver for the Western Montana Growers Cooperative (WMGC), a crucial cog in the FTC wheel. One of the bigger hurdles in getting local food to campus is the fact that small, local growers can’t always generate the product volume necessary to satisfy the UDS kitchens’ large appetite, and the purchasers don’t have time to call several different farms to piece together an order. Now they call WMGC and employees assemble the order with produce from a network of farms. This gives small farmers access to UM, a market they couldn’t otherwise reach.

Cohen and Brian Crego, UM’s head catering chef, unload strawberries, parsley, bagged salad, and cilantro. “Hey!” barks Cohen to the whole kitchen. “Give us some help here, let’s get her boxes back.”

Chef Siegel walks by with a bunch of cilantro. He’s smiling. “This is what I like. Look how clean it is. Some stuff we get is full of sand and we need to triple-wash it to get the sand out. With this, just give it a rinse and boom, ready for action.” As Siegel says this he deconstructs the cilantro with his knife and tosses it into a bowl of salsa he’s completing. Before Amanda even reaches the door, I’m testing it.

Besides the sheer quantity of food that an institution like UM requires, UDS also has needs regarding the form in which the food arrives. Rather than wash and clean hundreds of heads of lettuce, for example, UDS wants its salad to arrive ready to go, as with that bunch of cilantro, with no more than a rinse.

Enter the Mission Mountain Food Enterprise Center, a nonprofit based in Ronan that’s committed to helping local farmers succeed. This includes finding ways to extend the growing season so farmers can take better advantage of the considerably larger campus population in the spring and fall. The center also helps farmers add value to their products, turning apples into cider syrup, for example, or carrots into coins, krinkle-cuts, and matchsticks—and maybe some day Montana mustard seeds into mustard and Montana tomatoes into catsup. Such value-adding maneuvers can make the difference in getting a UM contract.

Those Pesky French Fries

“Value-added is where it’s at,” confirms Opitz, UDS purchasing manager. One of the big value-added products that’s on everybody’s mind these days is french fries. UDS has, by all accounts, a great relationship with Bausch Potatoes in Whitehall. Bausch potatoes are used in baked potatoes, hash browns, mashed potatoes … everything but the all-American french fry.

| FARM | PRODUCE | CITY/TOWN |

| Amaltheia Dairy LLC | goat cheeses | Belgrade |

| Bakery and Restaurant Foods | pasta | Missoula |

| Bausch Potato | potato, sausage | Whitehall |

| Beaverhead Honey | honey | Dillon |

| Big Sky Brewery | beer | Missoula |

| Big Sky Tea | tea | Thompson Falls |

| Big Timber Meats | beef, buffalo | Big Timber |

| Brentari Foods | salsa | Missoula |

| Caroline Ranch | beef, buffalo | Boulder |

| Cherry Apple Farm | apple cider | Hamilton |

| Chocolate Necessities | candies, caramels | Missoula |

| Churn Creek Ltd | granola | Sidney |

| Clark Fork Organics | produce | Missoula |

| Cream of the West | cereals, pancake mix | Harlowton |

| Edible Flowers | flowers | Missoula |

| ET Poultry/ET Farms | draper & ranger chicken | Belt |

| Farm to Market Pork | pork, ham, whole hog | Kalispell |

| Flathead Native AG Co-op | produce | Ronan |

| Garden City Fungi Mushrooms | mushrooms | Huson |

| Grandma Hoots | jalapeno jelly, chipotle | Florence |

| Great Grains Milling Company | grains | Scobey |

| Helen's Candies | candy bars, jam | Libby |

| Hi Country Snack Foods, Inc. | jerky | Lincoln |

| Home Acres Orchard | apples | Stevensville |

| Homestead Organics Farm, Inc. | produce | Hamilton |

| Huckleberry People | huckleberry products | Missoula |

| Hutterite Chicken | poultry | Choteau |

| John Knight/Mojo Foods | spices | Belt |

| K & S Greenhouses | tomatoes | Corvallis |

| Kettlehouse Brewing Co. | root beer, beer | Missoula |

| Knapp Foods Inc. | salsa | Helena |

| Lavender Lori | dried lavender | Missoula |

| Larry Evans | mushrooms | Missoula |

| Lifeline Farms | cheeses | Victor |

| Loring Foods | Mexican-style wontons | Loring |

| MeadowGold | dairy | Missoula |

| Mission Mountain Co-op | produce | Ronan |

| Montana Buffalo Outfit | beef, buffalo | Butte |

| Montana Milling, Inc. | grains | Great Falls |

| Montana Natural Beef | beef, buffalo | Ronan |

| Montana Range Meat Company | beef, buffalo | Billings |

| Montola Growers | oil | Culbertson |

| Natural Tomatoes | tomatoes | Chester |

| Ocean Beauty | seafood | Helena |

| Planetary Designs | chai, tea | Missoula |

| Ranchland Packing Co. | beef | Butte |

| Rocky MT Gourmet (Imperial) | beef | Missoula |

| Senorita's Specialty Foods | salsa | Manhattan |

| Service Specialty Distributors | tortillas | Lolo |

| Smoot Honey | honey | Power |

| Stampede Packing | sausage, andouille, links | Kalispell |

| Sweet Palace | candy | Philipsburg |

| Terrapin Farms | produce | Whitefish |

| The King's Cupboard | candies, caramels | Red Lodge |

| The Orchard at Flathead | cherry products | Bigfork |

| Tipu's Tiger | chai | Missoula |

| Totally Organic | tofu | St.Ignatius |

| Viki's Montana Classics | potato chips | Bigfork |

| VW Ice | ice | Missoula |

| Wee Sprouts | sprouts | East Missoula |

| Western Montana Growers Co-op | produce, buffalo, eggs | Arlee |

| Wheat Montana | grains, breads | Three Forks |

| White's Wholesale Meats | beef, buffalo | Ronan |

| Whiting Enterprises | chips, tortillas | Corvallis |

The problem with Bausch potatoes? They’re too fresh. Most fries today are coated with flour and then flash-frozen in a machine called an Instant Quick Freeze, or IQF. For about a year, UDS tried various ways to cook the fresh Bausch potatoes into a form that the students would like, even after twenty minutes under a heat lamp.

“Bausch potatoes, being natural, never frozen, uncoated, don’t hold up under the lamp,” says Opitz. “Their fries are extremely successful when cooked to order,” he says, “but we don’t do that.”

“We tried a blanched product, but it didn’t fit the flavor profile,” he says. “Multiple units worked on this, trying many things, but it didn’t work. Our students are very used to the corporate, heavily coated fry.” As it stands now, the french fry is the one big holdout in the All-Montana Burger meal. Even the fry oil comes from Montana—canola oil from Montola in Culbertson.

But the process of working on those french fries, the push and pull between the high ideals of the FTC program and the picky palates the program caters to, is what’s driving FTC to keep innovating. “We just continue to work with the vendors to see what kind of products to add to our menus,” LoParco says. “We’re looking to expand in any way that we can.”

To that end, and in service of its own mission, the Mission Mountain Food Enterprise Center is considering getting an IQF machine to help Montana potato growers tap UM’s considerable french fry market. Meanwhile, UDS is purchasing a vacuum-sealer, which will allow it to take advantage of seasonal surpluses by freezing produce for later use. Last year UDS tested the idea by freezing raspberries from Common Ground Farm in Arlee, which were used in dessert sauces throughout the year.

Chef Siegel calmly gushes over the possibilities. “Meats, chilis, sauces,” he muses. “It opens the door for us to blanch and freeze broccoli for later use in soup, or coulis. We could do tomato products …. We have a lot of freezer capacity.”

Paradigm Shifts and Real-world Impact

“What’s really important about the new equipment is that it’s indicative of the paradigm shift that UDS is willing to make,” explains Neva Hassanein. “Most institutions these days like everything ready and value-added. UDS is looking at ways to add value themselves.”

Hassanein has a knack for adding value to her students’ educations by finding them academic research projects with immediate, real-world impact. It was her environmental studies students—Claire Emery, Kira Pascoe, Shelly Connor, and Crissie McMullan—who put together the original Montana Mornings breakfast. As FTC has grown, successive students have worked closely with UDS to identify ways that more local products can be brought to campus.

Hassanein’s spring 2006 graduate course “Action Research in the Montana Food System” began a whole new round of inquiries into how to improve and expand the FTC program. She and her students traveled across Montana, interviewing growers, processors, and distributors who are part of the FTC program. They also did extensive surveys at UM to learn what the campus community thinks of the program and how it could better serve them. “The project,” says Hassanein, “is designed to produce research that’s aimed to improve FTC and make recommendations that get translated into change.”

Many of her students are doing their master’s thesis work in the FTC arena. Scott Kennedy is doing his project on SYSCO, UM’s primary food supplier. By all accounts, SYSCO has been very receptive to the FTC program, working hard to find local products. “The national CEO of SYSCO is talking about local food and the role of SYSCO as a distributor of local foods,” says Hassanein. “As it stands now, we don’t have a distribution infrastructure in Montana. Do we build one, or do we go with something that’s already going, like SYSCO?”

Another member of Hassanein’s Action Research Group is Kimberly Spielman, a graduate student in geography. She’s doing her thesis on a concept called food miles, or the number of miles a product travels from farm, through supply chain, to the consumer. Spielman has done extensive research comparing the food miles traveled by an FTC burger and fries with those traveled by a conventional equivalent made from ingredients purchased through SYSCO. By comparing the routes, from points of production to consumption, of beef, buns, potatoes, and oil, she found that, for fiscal year 2005, a year’s worth of non-local burgers and fries traveled 110,450 miles, while the FTC equivalent traveled 33,624 miles, burning 43,184 fewer gallons of diesel fuel. Nearly a million fewer pounds of carbon dioxide was released into the atmosphere via the local burger and fries. (Spielman’s research was conducted when Bausch potatoes were being used for the french fries.)

Meanwhile, veterans of the FTC program’s early days are out there, still doing the work. Lauren Caldwell, for example, recently released a book titled Eat Local, Feel Noble. Produced with support from the FTC program, the book offers “a tasty recipe for each week of the year, made entirely of local ingredients available during that week—fifty-two delicious recipes in total!”

Chrissy McMullan, another alum, heads an organization called Grow Montana, which has received money from the Kellogg Foundation and the Montana Department of Agriculture to research the potential of FTC-style programs in other institutions around the state: Missoula Public Schools, Montana State University in Bozeman, UM Western in Dillon, and Salish Kootenai College in Pablo.

It’s easy to imagine wave upon wave of students, with their hard-wired young adult energy, pushing the FTC program to new heights. LoParco, Siegel, Opitz, and the rest of UDS stand ready to collaborate. So do many others, including growers, distributors, and processors around the state.

Someday, and it won’t be long, the all-Montana burger meal will be a reality, with fries on the side, a pickle on top, and the special sauce of your choice.

Ari LeVaux, M.S. ’01, is a freelance writer in Missoula. He pens a syndicated food column, which appears in the Missoula Independent and other weekly newspapers.

Ari LeVaux, M.S. ’01, is a freelance writer in Missoula. He pens a syndicated food column, which appears in the Missoula Independent and other weekly newspapers.