When Speech Wasn't Free

UM project produces pardons for seventy-eight sedition convicts.by Patia Stephens

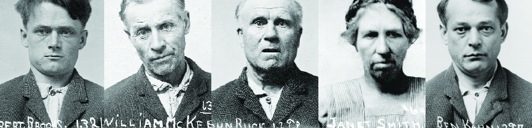

Photos Of Prisoners Courtesy Of The Montana Historical Society

Whereas, in America, free speech is a fundamental right in times of war and peace alike. – from the governor’s 2006 clemency proclamation

On May 3, UM law student Katie Olson spoke before a small crowd gathered in the rotunda of the Montana State Capitol in Helena. The occasion was the pardoning by Governor Brian Schweitzer of seventy-eight men and women convicted of unlawful speech nearly a century ago under the Montana Sedition Act of 1918.

Olson, a Great Falls native who, with eleven fellow students and two professors, had undertaken the pardon project that secured the governor’s clemency, described the experience as a “giant history lesson.”

“This is a little embarrassing [for] someone who’s grown up in Montana her whole life,” Olson told the audience, “but I had no idea that such a law had ever been passed.”

Indeed, the First World War sedition law—strictest in the nation and the model for a nearly identical federal law passed just months later—punished Montanans with prison sentences of up to twenty years and maximum fines of $20,000. The seventy-five men and three women were sent to prison for saying things as innocuous as “This is a rich man’s war.”

The former convicts took the stigma of the convictions to their graves. But decades and generations later more than forty of their descendants attended the ceremony to see them vindicated for the crime of speaking their minds.

What began last December as an abstract to Olson—something that had happened a long time ago to people now gone—became very real when she visited the Montana Historical Society in Helena and held the original prison records of those convicted of sedition in 1918.

“The interesting thing about these records,” Olson told the audience, “was that they each contained two photos: one of the individual taken right when they were admitted to prison and the second taken shortly thereafter, after they’d been processed through the system. The only thing that was different about these two photos was that in the first photo, these individuals had their hair, and in the second their heads had been shaved.

“And for some reason that juxtaposition just struck me,” she says. “That’s when I realized that we were dealing with real people—with people who’d been taken away from their families and charged needlessly with crimes.”

The convictions had serious repercussions for many of the families, some of whom are still recovering from the shame and secrecy two or three generations later. One eighty-nine-year-old woman, Marie Van Middlesworth, traveled from Medford, Oregon, to the ceremony, where she met her nieces and nephews for the first time. Van Middlesworth and her eleven siblings were split up when their father, Fay Rumsey, was convicted of sedition and sent to the state prison in Deer Lodge. The family homestead was lost and the children were sent to orphanages or farmed out to other families.

Governor Schweitzer greeted descendants at the ceremony with a heartfelt introduction about the importance of righting old wrongs, as well as a personal tale of his immigrant grandparents, forbidden from worshipping in their native German during the same wartime hysteria in Montana. “For those of you who are here to honor your ancestors,” Schweitzer said, “I say to you: They were patriots.

“For those of you who have traveled a long distance to Montana, welcome,” he said. “Welcome home.”

Another relative at the ceremony was Drew Briner, who read from his grandfather Herman Bausch’s beautifully written prison memoirs. Few eyes remained dry as Briner read of Bausch’s agony at being on a prison work crew in Deer Lodge when his toddler son, Walter, fell ill and died:

“While my own flesh and blood was being lowered seven feet into the bowels of the earth, I was standing in the mire, also seven feet beneath where the grasses grow, shoveling mud and stagnant waters, paying for the crimes I had not committed against the laws of God and man.”

Bausch, a pacifist who refused to buy Liberty Bonds in support of the war effort, had nearly been lynched in front of his wife and infant son by a mob that showed up on his doorstep near Billings. After being harangued and physically threatened, Bausch was arrested and convicted for saying in his defense: “I do not care anything about the Red, White, and Blue .... We should never have entered this war and this war should be stopped immediately and peace declared.”

Montana’s sedition law made it a crime to “utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, violent, scurrilous, contemptuous, slurring, or abusive language” about the U.S. government, its Constitution, military, or flag. It conveniently overlooked the First Amendment to the same Constitution, which states that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech ….”

It was that contradiction, and the hard work of Olson and other UM students, that led to the posthumous pardons.

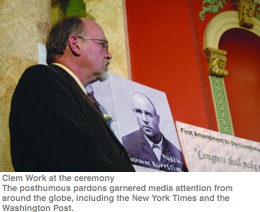

The project began with Professor Clem Work, author of Darkest Before Dawn: Sedition and Free Speech in the American West (2005: University of New Mexico Press). Work, who came to UM fifteen years ago from a senior editor position at U.S. News and World Report, directs the School of Journalism’s graduate studies program. Teaching media law, he became fascinated by Montana’s history of spectacular battles over speech issues.

He set out to answer a question: Why did Montana imprison people for speaking their minds?

Work researched Darkest Before Dawn in archives around the country, especially those of the Montana Historical Society. The resulting book is a compelling read that chronicles Montana’s, and to an extent the nation’s, understanding of freedom of speech during the tumultuous first three decades of the twentieth century.

A quiet, thoughtful man, Work never expected his scholarly effort to attract much attention. But at a reading last October at Missoula’s Fact and Fiction bookstore, he was asked by an audience member, “What’s next?” He responded from the heart: “In my box of dreams—I hope someday these people will be exonerated.”

Those words were enough to light a fire under an audience member, UM law Adjunct Assistant Professor Jeff Renz. Together, Renz and Work cooked up a “pardon project,” recruiting a group of students to conduct legal and genealogical research. Journalism students Caitlin Copple, Nicole Todd, and Bree Rafferty teamed with law students Olson, Jason Lazark, Peter Lacny, Laura Beth Hurd, Daniela Pavuk, Myshell Uhl, Kimberly Coburn, Stuart Segrest, and Maggie Weamer. The students divvied up the tasks that would result in a formal letter and brief that petitioned the governor for clemency.

“It seemed really daunting,” says Olson, who earned her law degree in May, just days after the pardoning ceremony in Helena. “We didn’t know if it was something we could really do. We thought, ‘How will this ever happen?’”

Remarkably, given the typical glacial speed of bureaucratic processes, the entire project was completed in little more than a semester. “It was amazing how it all came together,” Olson says. “To see the petition signed and the pardons granted in six months’ time was pretty incredible.”

First, to determine whether Montana could legally grant a posthumous pardon, Olson and her fellow students pored over the state’s 1889 and 1972 constitutions, looking for applicable wording. They researched records of the state’s Board of Pardons and Paroles to see if it had ever received any requests for posthumous pardons. They contacted every county clerk of court in the state, seeking trial transcripts and other records related to the 150 people prosecuted for sedition. They did criminal background checks to uncover any other convictions that might have been lurking in the backgrounds of those charged with sedition. (They didn’t find any.) They contacted historians and First Amendment scholars across the country seeking legal precedents.

They also did a lot of genealogical research. Work, who purchased a gold membership on Ancestry.com, says the students found genealogy a very different type of research from what they were accustomed to. “There was a lot of wheel-spinning going on,” Work says.

The search for family history and living descendants was complicated by name changes. Most of those convicted were first- or second-generation German or Austrian immigrants, and their surnames sometimes had several spelling variations or were changed altogether to escape the stigma of an ethnic name or a criminal conviction. Enforcement of the sedition law was capricious and often motivated by xenophobia, revenge, or jealousy.

Bree Rafferty, a 2006 journalism graduate, says the research was definitely character-building. “It was difficult keeping myself focused when I kept coming to dead ends,” she says. “It called for a lot of perseverance.” That perseverance paid off, though, when Rafferty found a granddaughter of August Lambrecht (who changed his name to Lambert after his prison sentence). “I got to speak with her only about a month before she passed away,” Rafferty says. “It was so cool to watch the puzzle of August Lambrecht fall into place. She said no one had known what had really happened. She was relieved to finally know what her grandfather had been taken to prison for. After doing so much work that seemed to be going nowhere, it was awesome to realize that what I was working on really made a difference for someone.”

Rafferty says meeting the families at the ceremony “brought everything together. As the past met the present, it revealed how much history and the things that happened in the past can affect the present,” she says. Work also says finding the families and seeing them reunited has been the most rewarding part of working on the book and pardon project. “Shame is just a psychological thing, but whole families were torn apart,” he says. “Generations later they’re still finding each other.”

To Olson, meeting the relatives and discovering that some hadn’t even known their family member had been in prison was revealing. “It really spoke of what a dark period it was,” she says. “The personal impact really drove home the importance of what we had done.”

Olson spent part of her research in Helena digging through a repository of records, looking for pardons granted in Montana. “The secretary of state has a warehouse there with all the state documents since the beginning of Montana history,” she says. “I found violent offenders, even murderers who had been pardoned, while the sedition convicts sometimes did more time in prison. It made me see the mob mentality at the time.”

Reading Darkest Before Dawn, it’s easy to wonder if the whole country went temporarily insane during the First World War. Work’s book chronicles the decline of fear and patriotism into hysteria and propaganda. Americans became terrified of spies, Huns, and the “enemy within.” Anything or anyone German was suspect; books were burned across the country, and in Montana, teaching and even preaching in German were forbidden.

Anyone perceived to be disloyal to America or its interests was seen as an outlaw and became a potential target for vigilante justice. Lumped in with the “disloyal” were members of the Industrial Workers of the World—called Wobblies—and other labor organizations that had spent a decade agitating for improved pay and working conditions. Union organizers found an especially receptive audience among the working men of Butte, home of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, which exerted a powerful influence over the state’s economy and politics and controlled most of the newspapers in Montana.

Newspapers, including the Helena Independent, editorialized for strict punishment of those who fomented rebellion. There was plenty of it going on. In 1917 Wobbly organizer Frank Little was kidnapped from his Butte boarding house in the middle of the night by a gang of masked men and hanged from a railroad trestle at the edge of town.

Incidents like these were used as arguments for the passage of Montana’s sedition law.

The rationale was that arrests and convictions for the outrage of disloyalty would prevent mobs of citizens from taking the law into their own hands.

Some were convicted of sedition based on drunken utterances in saloons. Many of those charged spoke in crass or vulgar language. Many were uneducated. Others simply said the wrong thing to the wrong person in casual conversation.

Ben Kahn, a liquor salesman visiting Red Lodge, earned a sentence of seven and a half to twenty years in prison for saying that wartime food regulations were “a big joke.” A rancher named Martin Wehinger got three to six years in Deer Lodge for opining that the United States “had no business sticking our nose in [the war] and we should get licked for doing so.” Near Miles City, a postmistress and rancher’s wife named Janet Smith received five to ten years for saying citizens should loose “the stock into the crops to prevent helping the government.”

Others were articulate and principled, like the well-read Herman Bausch, whose memoirs explained his refusal to buy war bonds: “I am opposed to war. All war, I think, is aggressive and oppressive—but if Wall Street plutocrats insist upon further bloodshed, why then, let them also finance it. … I will not contribute to continuation of this world calamity.”

Bausch, sentenced to four to eight years, ended up serving twenty-eight months with the violent offenders in Deer Lodge. The longest sedition sentence served was thirty-six months, and the last sedition prisoner was released in late 1921, three years after fighting ended.

At the pardoning ceremony, Bausch’s words read by his grandson rang out in the Capitol building, mourning the death of his son, the loss of years, money, and crops, and “the tears and anguish of my wife, her rude awakening from idyllic regions of beauty and innocence.

“I shall start out afresh to plant and build upon the ruins of the past,” he wrote. “My hopes are modified but not diminished. I have not lost faith in the good, the holy, and the true. But I have found that contest in battle must precede all true progress, all enlightenment, and in that spirit I shall strive and labor onward.”

Patia Stephens is a 2000 graduate of UM’s journalism school and is currently working on an MFA in the Creative Writing Program. She is an editor and Web content manager for University Relations and an award-winning writer for the Montanan.

Patia Stephens is a 2000 graduate of UM’s journalism school and is currently working on an MFA in the Creative Writing Program. She is an editor and Web content manager for University Relations and an award-winning writer for the Montanan.