Guardians of History

UM’s Archives and Special Collections protects priceless lore and artifacts

By Cary Shimek

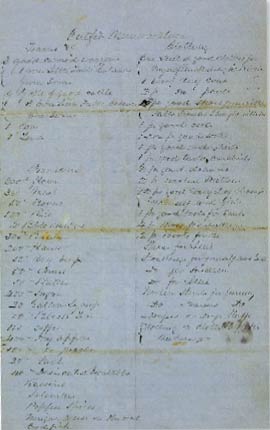

A letter dated from November 1863 lists items a family should bring to make it in Virginia City. The letter is part of the Fergus papers, which are preserved in UM’s Archives and Special Collections.

The energetic Scottish immigrant had been going through a rough patch. A national depression in 1857 wiped out the Minnesota manufacturing company he co-owned. Then his expedition to the gold fields at Pikes Peak, Colo., resulted in little else than endless eighteen-hour workdays with pan and pickax.

His fortunes rose in what would become the Montana Territory, with modest gold strikes at both Bannack and Virginia City. He even had a part-time job recording many of the mining claims. Then it was time for his wife and kids to make the journey from Minnesota and join him on the frontier.

We know all this because a collection of Fergus’ papers have been preserved in UM’s Archives and Special Collections. A letter dated “Virginia City Nov [sic] 21st 1863” even told the family what they should bring to the mining boomtown. Items such as three good covered wagons, nine yoke of good cattle, one cow, one lamb, 600 pounds of flour, 400 pounds of sugar, twenty gallons of syrup, 400 dry apples, and two pair of good drawers are listed in the letter’s “Outfit Memorandum.”

Fergus also underlines the following advice: “… and never let one of the children go out or in the waggon [sic] under any circumstance without stopping it, as many get killed or injured by the waggon [sic] running over them.”

The family arrived safely on August 15, 1864. Fergus went on to become an important figure in the development of Montana, and the country near Lewistown where he eventually ranched became known as Fergus County.

Mansfield Library archivist Donna McCrea says the Fergus “Outfit Memorandum” is one of the tools she uses to get visiting students excited about the untold stories hidden in Archives and Special Collections, which houses rare and irreplaceable material on Level Four of the library.

“This letter is in Mylar because it gets handled so much,” McCrea says. “Kids are amazed they get to touch something from 1864. Most of them have heard about travel by covered wagon, but this kind of authenticates that whole idea for them.”

Archives and Special Collections contains about 12,000 linear feet of stored materials—enough to cover more than two miles of shelves. Items include unusual books, manuscripts, pamphlets, photographs, negatives, maps, taped interviews, films, microfilms, architectural drawings, University records, diaries, and unique artifacts.

Mansfield Library archivist Donna McCrea reaches for a box of documents. Archives and Special Collections contains enough materials to cover more than two miles of shelves.

Archival materials can’t be checked out, but students, scholars, and the general public are welcome to peruse items in a comfortable reading room. Pages also can be copied, and digital cameras are permitted (though hand-held scanners are not allowed because of their potential to harm materials).

“We don’t allow things to be checked out because it’s our job to prevent damage and make sure these things stay around,” McCrea says. “Oftentimes they are the only ones left in the world.”

The department charges for page copies and reproductions of historical photos. Fees also are charged to entities wishing to publish materials from archives that will make a profit, but those costs are waived for government and nonprofit organizations.

“We probably make several thousand dollars annually from use fees,” she says. “It’s not a lot, but it’s something. We charge lower fees than a lot of places.”

McCrea says an appraiser would find the department’s holdings worth in excess of $1 million, but many items are truly one-of-a-kind and priceless. Fire, flood, or theft could erase a valuable chunk of Montana’s history, so the collections are guarded by locked doors and an expensive misting sprinkler system designed to avoid drenching archival materials in the event of fire. Most items also are stored in acid-free boxes that help protect them from light and dust.

Though Archives and Special Collections contains a lot of old stuff, the department itself isn’t particularly ancient. It was founded in 1968 when UM hired its first official archivist, Dale Johnson. Before that, UM’s records and valuable oddities were hoarded in various spots around campus.

“My understanding is that there was a treasure room in the beginning,” McCrea says. “People would give their book collection to the library, and the special or really rare books would go into the treasure room.”

The idea to establish a campus archives took off in 1965 with the arrival of history Professor K. Ross Toole. McCrea says he had the vision to build collections on campus to support doctoral research for his history students. At that time, Toole’s students were forced to travel to places such as Helena, Great Falls, or Washington, D.C., to work on their dissertations.

“He went and talked to a lot of people around the state and did a lot of proactive work to bring collections to campus,” she says. “It was my understanding that these were stored in the halls of the history department until the fire marshal declared, ‘No more!’”

The history department’s collections were then moved to the library, though history still funded and supported archives. Those duties eventually passed to the library, and by the mid-1970s, Archives and Special Collections was located alongside government documents in the newly built library’s lowest level. (Archives officially was dubbed the K. Ross Toole Archives in 1982 after the historian’s death.)

“The basement wasn’t an ideal situation,” McCrea says. “If you want to showcase what makes your library unique, having the department locked away in the basement is not the best way to do it.”

Former library Dean Frank D’Andraia had the idea to move archives into the light to a more user-friendly environment. So the department rose, so to speak, in October 2002, when it relocated to the library’s top floor. The accessible new digs include a relaxing reading room and exhibit cases where books and other archival items are displayed for the public.

The renovations didn’t stop there. At this writing, a portion of the department is being remodeled, with the addition of a reference room to support the collections and Montana research. The room will include a cross-section of regional and historical maps.

Jordan Goffin, UM’s special collections librarian, says about 2,500 people visit the department every year. “We really get an astonishing amount of use,” he says. “I’ve worked at some larger collections, and I would say they didn’t get that much more traffic than we do.” McCrea says archives provides a rewarding work environment. “We are excited by the opportunity to connect information to people and sources that are sometimes challenging to find because they are so unique,” she says. “Every day you learn something new, either because somebody brings you their research question and you think of things in a new way, or you have the opportunity to do some type of research you have never done before.”

Since nearly everything stored in the department is valuable or irreplaceable, McCrea and Goffin have a hard time pinpointing favorite items. During a stroll into the stacks, Goffin talks about an interesting collection of early items printed from Hawaii, for instance, or points out American Woods, a multi-volume work that contains pages of actual wood samples—some from trees now extinct.

McCrea mentions the Mansfield Collection as a favorite.

“[Mike] Mansfield had so much impact, and the fact we have this body of material that people can come and see is remarkable,” she says. “We don’t have just one letter, but the host of letters and memos leading up to that one letter and the others that follow, so you get the full story in context. That’s what’s so powerful about archival collections—you get to see everything and make your own decisions based on your own research.”

Goffin said those working with archival material “have to be into the long-term meaning of things. We have to put things together and think of what might be useful to people 150 years from now. Some of our collections might not get used daily, but they are going to be used a lot eventually.”

A beaded armlet with shell ornaments from the Crow Tribe and beaded moccasins from the Cheyenne Tribe are among the artifacts in the Frank Bird Linderman Collection, which was donated to UM by his heirs.

Most items in Archives and Special Collections were donated. Bonnie Allen, dean of library services, says it’s not unusual for people to bring in family letters, scrapbooks, and photos that had been lost in attics somewhere and ask, ‘Would you like this?’ “And our answer is yes, yes, yes,” Allen says, “especially if items have to do with the history of Montana.”

Sometimes circulating items in the library’s main collection stay on the shelves so long they become valuable and then are moved to special collections. Goffin says that happened recently with a small 1840s atlas noticed by one of his preservationists.

Allen says the library has crafted a “visioning document” outlining the collecting priorities for Archives and Special Collections. Subjects such as UM, Montana, American Indians, and the environmental movement are targeted topics. The document describes the types of works the department will pursue.

Allen and her staff spend a lot of time wooing potential donors, and sometimes the library pays for particularly noteworthy collections, such as the papers of acclaimed poet and UM Professor Patricia Goedicke. The library scraped together funds from donors and Friends of the Library, a volunteer group that raises money for the library.

“But we have lost collections because we couldn’t afford them,” Allen says. “Sometimes it becomes a bidding war.”

That’s what happened with the papers of Richard Hugo, an accomplished writer and longtime UM faculty member. UM tried to bring the collection to Montana but was outbid by Hugo’s alma mater, the University of Washington.

Some donors also need a lot of convincing before they contribute. Allen says she is pursuing a massive collection right now whose potential donors UM has wooed for seventeen years.

“Sometimes these things can’t be rushed,” she says. “Stay tuned.”

During a remarkable Montana life, Frank Bird Linderman (1869-1938) was a trapper, insurance agent, politician, and more. He also was a writer, and his most lasting legacy may be the books he published that document American Indian stories and the changing West. By the time he died, Linderman had been adopted into three tribes: the Blackfeet, the Cree, and the Crow.

Linderman’s heirs wanted to ensure his life’s work was preserved for all time for future scholars to study. So, free of charge, they donated his papers and a collection of unique Native artifacts to Archives and Special Collections.

Sally Hatfield, Linderman’s granddaughter and a UM alum, says, “We knew it was important to donate his papers so they could be studied and used by scholars. So we gave all his manuscripts, photographs, letters, and Indian artifacts to the Mansfield Library to create a study collection for others to learn from.

“He gave a lot to Montana, so it was important to keep his collection together for people curious about the forming of the state—so they can learn where it all came from. I love the idea of future generations using his work.”

Here is a sampling of the interesting gems in UM‘s Archives and Special Collections:

■ the first two diplomas awarded by UM. Ella Robb Glenny and Eloise Knowles graduated June 8, 1898. Glenny went on to a career as an Iowa schoolteacher, and Knowles worked at UM for a number of years following graduation.

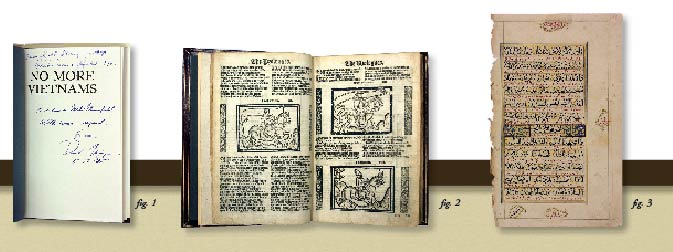

■ the papers of Mike Mansfield, the remarkable Montana statesman who served in Congress from 1943 to 1977 and became the country’s longest-serving U.S. Senate majority leader. The collection covers more than 2,500 linear feet and includes 600 artifacts, such as the pen used by President Lyndon Johnson to sign into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and a personalized signed copy of No More Vietnams by Richard Nixon.

■ a 1561 edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. At 447 years old, it’s the University’s oldest book.

■ a copper-metal dinner menu made in Butte in honor of a visit from Theodore Roosevelt on May 27, 1903. Menu items include potage à la Theodore, truîte de montagne sautée à la Meunière and punch à la Montana.

■ a single leaf (front and back of one page) from a 1207 Koran. In remarkable shape, the manuscript’s beautiful Arabic writing was hand-drawn in black, red, and gold inks. The item is part of a leaf book, which contains pages from other old writings.

■ the first issue of Big Sky Country’s first newspaper, The Montana Post, which was published Aug. 27, 1864, in Virginia City.

■ a volume of rare American Indian ledger art. Eighteen drawings on brown, brittle ledger notebook pages show ceremonies and life from the late 1800s. The drawings are believed to be by Walter Bone Shirt (his Indian name was Never Misses), a Brulé Lakota known to have created commissioned art on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The ledger came to UM in 1962 from Genevieve Prochnow, whose father served in the U.S. Army on that reservation.

■ an 1890 book titled Studies of Western Life. Though only twenty-four pages long, it was the first book by Charles M. Russell, Montana’s famed cowboy artist. The book was owned by prominent Montana politician Joseph Dixon, a former governor and U.S. senator.

■ a twenty-volume set of Edward S. Curtis’ The North American Indian, which was published from 1907 to 1930. It is likely the library’s most valuable holding. A copy of the work auctioned elsewhere recently sold for more than $1 million.

■ a book once owned by Adolf Hitler. It’s a volume of drawings showing how Rome was decorated with Nazi symbols for a state visit from the Führer. Lt. Gen. Frank Milburn, a former UM professor and football coach, received the book after his troops liberated Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s chalet in the Alps. Milburn eventually gave the book to campus.

■ the earliest authorized edition of the Lewis and Clark journals. The two volumes, bound in red morocco leather, were once owned by Henry Villard, the German-born financier who brought the railroad to Missoula in 1883 and for a time controlled most major transportation in the Pacific Northwest.

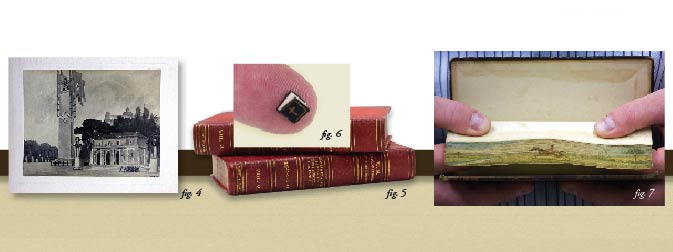

■ several miniature books. One, about as big as a baby’s fingernail, contains the Lord’s Prayer written in seven languages and must be read with a magnifying lens. It was the smallest book in the world when published in the 1950s. Another tiny book, a little larger than an adult fingernail, contains 239 pages with the complete speeches of Abraham Lincoln.

■ about 100,000 historical photographic images, as well as maps and architectural drawings. One noteworthy collection of about 2,000 images is by Morton J. Elrod, UM’s first science professor who doubled as campus photographer. Many of his images were created on large glass negatives.

■ an 1817 book titled The Fashionable World Displayed, which contains a scene of a horse and rider painted on the edge of the book’s leaves. The picture is invisible until the pages are flexed.

Cary Shimek is senior news editor with UM’s University Relations, where he has worked for more than ten years. He manages Vision and Research View, UM’s research publications, and is an award-winning science writer.