The Magazine of The University of Montana

Jam Session

Jeff Ament ’85 may only have attended UM for a short time, but in those years he discovered the bass guitar and the seeds to grow his wildest dreams.

By NATE SCHWEBER

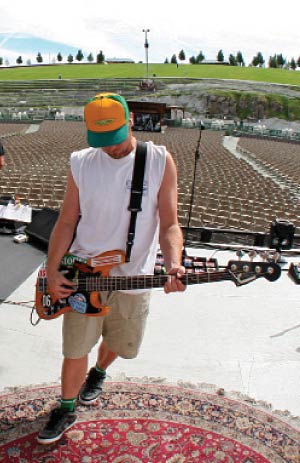

Top: Jeff Ament at Yellowstone National Park; Bottom: Ament in his Missoula recording studio

Author Pete Fromm tells a story of walking his young sons past the skateboard park in Great Falls, which was then having finishing touches put on it by a few dust-covered laborers wailing on grinders, smoothing the cement.

“One of them bails up out of the hole and said, ‘Hey, you’re Pete Fromm,’” he chuckles. “I said, ‘I know.’”

With all due self-deprecation, Fromm admits figuring that in a Cascade County meeting between a cement monkey and a celebrated regional author he would be the more famous. Then his dusty admirer introduced himself. Jeff Ament. Bass player for Pearl Jam, one of America’s premier rock bands, whose record sales roughly equal Montana’s population times sixty.

“He said he loved my book As Cool As I Am and asked if there was anything he could do to help,” Fromm says. “I’d never met him, and here he was saying he wanted to write a good blurb for me.”

To Ament’s friends, Fromm’s story is typical of the hard-working, culturally aware dude who grew up in Big Sandy and kicks out the jams to support people who empathize with the kind of folks he grew up around. To many of Ament’s fans and even his fellow Missoulians, he remains a curiosity. Resident rock star. Benefactor. Skateboarder. Prodigal Montanan. A man who fled the confines of Montana for Seattle and then returned—his wildest dreams realized—because what was once his constriction transformed into his anchor.

“Moving back meant that I would always have friends, a place to hang, write, and a place to get back in contact with who I was,” Ament says from his home in Missoula.

Do The Evolution

| “ | Moving back meant that I would always have friends, a place to hang, write, and a place to get back in contact with who I was - Jeff Ament | ” |

Ament was born in March 1963 in Havre, the first of George and Penny Ament’s five children. Two months later the family moved to Big Sandy, populated then by only 800 residents. George Ament, the town barber, learned fast that his family couldn’t eat on hair clippings alone, so he also drove a school bus, sold insurance and shoes, and raised cows, pigs, and chickens. His eldest son often worked alongside him, sometimes on a farm next to future Sen. Jon Tester’s. This instilled in him an ethic he later applied to music.

“My dad taught me that you’ve got to work your ass off in order to survive,” Ament says. “I sort of despised him for it at the time, but I have him to blame for a lot of the good things that happened to me because I have a lot of drive, and I’m not afraid to work hard.”

He discovered punk rock through magazines and sent away for homemade tapes. When he was a senior, he took a few guitar lessons, though he preferred the energy of punk to the jangle of the folk chords he learned. A cool cousin in California turned him on to skateboarding, and Ament took to the sport so wholeheartedly he became the first kid in Big Sandy, possibly in the state, to build a ramp in his backyard. A gifted athlete, Ament says he was lucky to live in a community small enough that he could be both the star high school hoopster and the town punk.

“I wouldn’t have had the freedom to do that if I’d lived in a larger place,” Ament says. “Like Havre.”

Penny Ament remembers her firstborn as hardworking, adventurous, and expressive.

“He was definitely an achiever and had so many talents, whether it was taking part in all the sports he loved, riding his skateboard, listening to music, or creating a piece of his art,” she wrote in an e-mail.

Ament remembers that he dreamed of one day designing album covers for rock bands.

Suffice to say, he got his wish.

Nothing As It Seems

Ament tunes his guitar during a soundcheck at the Gorge Ampitheatre in George, Wash.

In spring 2009 Pearl Jam played in Missoula, but the only audience was the four walls of Ament’s home near Blue Mountain. Some songs that the band hammered out—“Supersonic,” “Force of Nature,” “Got Some,” and “Amongst the Waves”—appear on the band’s new album Backspacer. The band convened at Ament’s house not at his urging, but after lobbying by guitarist Mike McCready.

“Mike’s been doing the sales pitch that this is a good place to get stuff done,” Ament says. “Sometimes in Seattle there are a lot of distractions.”

Those distractions, including scores of other artists, rock havens, museums, theaters, and a steady flow of groundbreaking bands, drew Ament to Seattle from Missoula in the early 1980s.

Inspired by album covers, Ament enrolled at UM in the fall of 1981 to study graphic design, but quickly realized he didn’t like the program’s direction. No longer in a tiny town where he could easily bridge the gap between arts and sports, he didn’t go out for any UM athletic teams. Much of his time was spent skateboarding the humps outside the University Center, which were then brick and are now grass. He also traded his guitar for a bass and on the sixth floor of Jesse Hall, began to play. With some skating buddies he formed his first band, Deranged Diction, probably Montana’s first hardcore band, and quickly set about making tapes and playing gigs.

“Things weren’t working out in school the way I wanted them to,” Ament says. “I was running out of money, my student loans were piling up, and it just wasn’t making sense to me. I thought I’d play basketball and be an art student, and suddenly I was more of a punk rocker getting a band together having more fun skateboarding.”

Erik Cushman, co-founder of the Missoula Independent, met Ament at the UM dining hall in 1982. The pair bonded over punk rock, and two weeks later, sporting what Ament called “Joe Strummer Mohawks,” road-tripped to Seattle to see The Clash, The Who, and X.

“There wasn’t a profound moment in Seattle where he said, ‘This is it,’” Cushman says. “He didn’t have to say it; there just wasn’t any opportunity for him to make it in Missoula as a musician.”

After two years at UM, Ament moved to the Emerald City in 1983 and got a full-time job at a coffee shop. He brought Deranged Diction with him, but then went on to form proto-grunge outfits Green River and Mother Love Bone. Exhibiting the drive he brought from Big Sandy, Ament pushed his bandmates hard.

“I had something to prove to myself, to my dad—I was going to make something out of this, even if it was just making a handful of records and traveling around the states,” Ament says. “Going home with my tail between my legs was the last thing I was going to do.”

Ament fostered that attitude within guitarists McCready and Stone Gossard. Then they met a singer named Eddie Vedder. When their talent and work converged, everything changed.

“Be careful what you wish for,” Ament says.

Man Of The Hour

Before Pearl Jam’s encore at Washington-Grizzly Stadium in the summer of 1998, Ament took the microphone and thanked his friend Truxton Rolfe, then student director for UM Productions, for making possible the big gig in front of around 20,000 fans. Most people never stand in front of a crowd that vast. For Ament, it’s just another day at the office.

“There’s no way to explain what it’s like, the magnitude of it,” Rolfe says. “If you haven’t been there, you’ll just never know.”

Things got weird for Ament in 1992. After four months touring in support of Pearl Jam’s booming debut album, Ten, he returned, exhausted, to his home in Seattle and got . . . stares. Shopping at his local grocery store. Buying coffee. Reading the newspaper.

“It would be insane,” Ament says. “All these people would be staring at me.”

Around this time the only solace Ament got was when he visited his family in Montana. He said he retraced places where he felt comfortable as a kid—Flathead Lake, Glacier Park, Missoula. In moments stolen from Pearl Jam’s rigorous schedule, Ament went on hikes and mountain bike rides. He floated the Blackfoot and sailed Flathead. Nobody stared.

“Every time I came back to Montana, I felt like I got grounded,” he says. “I felt like I was actually dealing with everything we were going through better than the rest of the guys in the band.”

Ament reconnected with college pal Cushman. The two took a Sunday drive down the Bitterroot, talked real estate, and took pictures. One that Ament snapped of a goat wound up on the cover of Pearl Jam’s second album, Vs., which sold 7 million copies. Cushman introduced Ament to Tim Bierman, then a local musician and fixture at Rockin Rudy’s.

“He just knew Missoula was where he needed to be,” says Bierman, a close friend who today is president of Pearl Jam’s fan club.

In April 2009 Ament made headlines when he was tackled by a knife-wielding attacker outside a recording studio in Atlanta, the jarring security video of which is on YouTube. Though Ament says he’s fine and downplayed the incident by adding he was mugged at gunpoint within six months of moving to Seattle, it goes without saying that such events are unlikely in Missoula.

“As soon as we got our first check for $90,000,” Ament says, “I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to buy a house out here.’”

Even Flow

Clockwise from top: Ament with his family; Riding down a halfpipe during a 1979 skate contest in Helena; With his longtime partner, Pandora, at the top of Mount Kilimanjaro; With his Big Sandy freshman basketball team in 1977 (seen back row, far left).

Pearl Jam last rocked the Missoula public in support of Big Sandy native Jon Tester’s successful 2006 Senate run. While the band has a reputation for political activism, the connection to Tester was all Ament.

“Jeff was literally the first person I called when I decided to run for Senate,” says Tester, who added that Ament’s father gave him his first trademark flattop. “Without Pearl Jam early on in that campaign, we would never have been able to stay afloat.”

Though Ament moved back to Montana to lead a more anonymous life, settling in with his longtime partner, Pandora Andre–Beaty, he gives money and time, and uses his name when necessary, to boost people and organizations that he believes make the community better.

Chris Bacon, president of the Montana Skatepark Association, says Ament helped the group secure a $50,000 grant through Pearl Jam’s charitable foundation to build the park in Missoula, which opened in 2006. Association Secretary Ross Peterson called Ament a “silent caregiver” most comfortable in the guise of regular guy, not rock star.

“He even seemed embarrassed a few summers ago when he was recognized by a fan while helping direct traffic at a Missoula Skatepark concert fundraiser,” Peterson wrote in an e-mail. “(Yes, he volunteered his time wearing a reflective vest and standing in the hot sun, just like everyone else.)”

Tom Webster, director of UM’s University Theatre and an adjunct professor in the business school, routinely invites Ament to guest lecture, which his students love.

“It would be like when I was in high school and they brought in John Paul Jones from Led Zeppelin to talk to us,” Webster says.

Ament credits his level of involvement to growing up in Big Sandy and wanting to make sure kids have the things he wishes he’d had.

“It comes from being in a small town, watching both my parents be super-involved with the community, whether it was kids needing swings or getting a basketball hoop up at a grade school,” he says. “Plus I’ve always had a magnet that’s pulled me toward giving kids things to do, whether it’s basketball courts or camps or skateboard parks.”

Author Fromm relishes telling the epilogue to his story. Shortly after Ament sent him the book blurb, Fromm received a large box in the mail. Inside were two nice skateboards and a note.

It read, “Hey, I thought your kids could use some decks. Jeff.”

Web Exclusive Q&A with

Pearl Jam bassist Jeff Ament ’85

Montanan: Tell me your thoughts on the Missoula skate park, which you were instrumental in building.

Ament: The great thing is I get to use it, too. That project I felt I could not only bring money to it but I’ve been to more than 100 skate parks over the world, so I know the good things and bad things. The skateboard park thing, I think, was a little bit harder to get done because most of the older generations don’t understand what that is. I explain it as it’s kind of like our generation’s version of Harley Davidsons.

Montanan: How did you start playing bass guitar?

Ament: I was into music when I was really young. My friend Reggie and I were rock music fanatics. We read [rock magazines] Circus and Creem. Punk rock was largely the thing that told me I could do it. It was simple and had the kind of energy I wanted. I started playing bass fall of 1981, on the sixth floor of Jesse Hall. Part of it was I had a guitar that I brought to school and I’d taken a few lessons in high school and there was a guy who I met on my floor who was in some punk rock bands in L.A. and his family moved to Butte. He could play both bass and guitar. He had a 1977 Fender Precision bass that he traded me for my Gibson SG.

Montanan: It’s been written that in some of your early bands you pushed your bandmates hard and even lobbied to make commercially successful music, which was a notion they thought was sort of un-punk rock.

Ament: No, that’s not true. I know it’s written on Wikipedia. The thing is, I was in it a little bit more, I didn’t really have a lot of patience for just f***in’ around and doing stuff just for fun. I had a full-time job, none of those guys had full-time jobs, and I wasn’t getting my education and my rent paid for. I said, “I’m going to make a go of this in my twenties. I want to make music. I want to make records. I want to tour. I want to make the most of being in a band. I want to take it seriously.” It wasn’t about being a rock star. I’m as much or more DIY [do-it-yourself] now than I was in ’92. Pearl Jam is putting out its own record this year, and we’re 100 percent in control of every creative aspect of it.

Montanan: If you weren’t driven by a huge desire for commercial success, where did your drive come from?

Ament: That all came from my dad. He taught me that you’ve got to work your ass off in order to survive. My dad probably for my entire life was living paycheck to paycheck. He was intense, and I had to work with him a lot. I sort of despised him for a lot of it, but I have him to blame for a lot of the good things that happened to me because I have a lot of drive and am not afraid to work hard.

Montanan: You moved back to Missoula in part because of the stresses of fame in Seattle. Did you ever have any similar problems in Missoula?

Ament: The only trouble I ever had in Missoula was from people from out of town. In Montana they were respectful or didn’t give a s**t. I appreciate people not really caring that much.

Montanan: Does where you live affect your creativity?

Ament: I always say I moved back because I work best and am most creative when I’m moving at a certain pace. Sometimes that Seattle pace is too much, there’s too much buzz. Missoula has enough of a cultural life that I can go in and out of that buzz. I can go in and get my little piece of culture, listen to a record, or see a movie or see some art and get a little poke and then hole up in my room and play guitar, paint, skateboard, whatever gets me excited. I never get bored, and I think that’s partly from being raised in small town. My imagination is pretty solid. I’m still into all the same s**t I was into when I was twelve. If I’ve got a guitar or a skateboard or a basketball, there’s not a chance in hell I’m going to be bored.

Email Article

Email Article