The Magazine of The University of Montana

The Brotherhood and the Business

Through thrills and trials in the NFL, gridiron greats find family in Griz Nation

By KEVIN VAN VALKENBURG

Colt Anderson (left) and Colin Dow (right) both were signed to NFL teams this year. Anderson will play for the Minnesota Vikings. Dow’s career with the Cincinnati Bengals ended before it began when he learned a back problem would prevent him from playing with the team.

Some nights, after a long day of fishing or working in his garden, Kirk Scrafford will fall asleep and dream, ever so briefly, about football.

It’s not the NFL he dreams of, even though his nine-year career as an offensive lineman with the Cincinnati Bengals, the Denver Broncos, and the San Francisco 49ers is what earned him the quiet, peaceful life he’s living now on an 85-acre piece of land nestled in the Bitterroot Valley between Lolo and Florence.

To Scrafford, the NFL was a business: lucrative, competitive, exhausting, and thrilling. But in the end, just a business, as ruthless as the next. When he decided the game had abused his body a bit too much, he was done with it, content to walk away even though he probably could have kept playing, and there have been no lingering questions that his decision was rash.

In his dreams, however, Grizzly football will occasionally appear, even though this fall will mark twenty years since he put on a Grizzly helmet. In describing this strange phenomenon, Scrafford can’t help but laugh at himself. There is a playfulness in his voice that, on the phone, makes him sound like he might still be a big goofy teenager.

“Every once in a while, I dream that somebody tells me I have an extra year of eligibility and I’m going back to play,” Scrafford says. “But in the dream, I always end up looking for my uniform, or looking for my shoes, and I can’t find them and I’m panicked. I hear it’s pretty common.”

Grizzly football, to Scrafford and countless others, is a family—a big, messy, diverse, loyal family that is constantly evolving, but also forever remaining fundamentally the same.

As is often the case with big families, there is no easy way to tell their entire story. There are too many roads to travel, and too many tales to digest. But you can get a sense of some of it if you’re willing to pause, just for a moment at each generation, and listen to the stories.

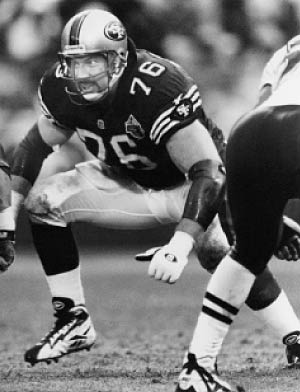

Kirk Scrafford prepares to attack an opponent during his third year playing for the San Francisco 49ers in 1997.

Every generation of Grizzly football dating back to the 1920s has produced a handful of NFL players—some of them Pro Bowlers and many of them journeymen. And while Scrafford doesn’t quite represent the genesis of that lineage, he’s darn close. It was, after all, his sophomore year in 1986 that ushered in the modern era of Grizzly football with the introduction of Washington-Grizzly Stadium.

“When we used to play at Dornblaser Stadium, we’d be lucky to get 1,000 people. A lot of them would put bags over their heads because we weren’t very good,” Scrafford says, laughing. “We would change into our uniforms someplace on campus and then be bused over before the game. I remember we had a little hut next to the field where we went for halftime. To see how huge it is now, to see them filling up that stadium every week with all those people, for me, it’s just amazing.”

The stadium isn’t the only thing that’s changed over the years. Scrafford was 210 pounds when he graduated from Billings West High School, and throughout his NFL career, he rarely weighed more than 275. During his rookie year with the Bengals, his first start came on the road against the Los Angeles Raiders and Raiders defensive end Howie Long, a future Hall of Famer.

“I remember Howie said to me, ‘Shouldn’t you be playing baseball instead?’” Scrafford says. “LA was an intimidating scene in those days. Everyone in the stands looked like they’d just gotten a ticket out of jail. There were more fights in the stands than there were on the field.”

Scrafford, though, was a fighter with superb technique, and over the course of his career, he regularly held his own against some of the best defensive ends of his era. A persistent neck injury eventually bothered him enough that he decided to retire after the 1997 season with San Francisco, but midway through 1998, his 49er teammates talked him into coming back for one more playoff run.

Scrafford was in charge of blocking Reggie White on the final play when Steve Young threw his game-winning touchdown pass to Terrell Owens to beat the Green Bay Packers in the NFC Wild Card game.

“Everybody remembers that catch, but people forget (Owens) dropped about five passes before that,” Scrafford says. “If he’d have caught those five passes, it wouldn’t have come down to that last play.”

Scrafford spends most of his time outdoors these days, fishing one of the many ponds and creeks on his land and hunting white-tailed deer. He works in his garden often, mostly because he enjoys the serenity of it. Occasionally, he likes to listen to Grizzly games on the radio, and he keeps in touch with several of his old teammates. He tries to take his daughters, ages ten and eight, to a couple of games a year, in part because he wants to show them where their father came from.

“I think they like watching the mascot more than the football,” Scrafford says.

In 2006, Scott Gragg was checking his e-mail. He noticed that his old high school coach in Silverton, Oreg., had sent him a note, letting Gragg know he was resigning.

It was one of those moments in life that seems important only in retrospect.

“I deleted it from my inbox, and I didn’t think much about it,” Gragg says. “But the truth is, it never really left my mind.”

Scott Gragg talks to his players, the Silverton Foxes, after the team won a playoff game against Oregon's Hillsboro High School in 2008.

At 6-foot-8 and 320 pounds, Gragg was one of the biggest, and best, offensive linemen ever to wear a Griz uniform. He was drafted in the second round by the New York Giants in 1995, and when the e-mail arrived, he had just finished his eleventh season in the NFL, a one-year stint with the New York Jets.

“I started thinking about what the rest of my career would look like—a series of one-year deals, having to move my wife and kids to different areas of the country,” Gragg says. “Suddenly, it made more sense to go somewhere my wife and I were familiar with, where we felt comfortable.”

He told the Jets he was retiring, dusted off his UM math degree, and applied for his temporary teaching license with an eye on getting his master’s. In a relatively short time, the biggest offensive lineman in Grizzly football history became the biggest high school football coach in Oregon history.

“I think whenever you feel like you have a responsibility to pass on the things you’ve learned to the next generation, it’s going to be a big determining factor in what you choose to do,” says Gragg, who is now entering in his fourth year as the head coach of the Silverton Foxes. “When you work in a field where the motivation to play is more out of passion than incentive, it’s a lot of fun to be a part of that process.”

Much of Gragg’s football career feels like a blur. The important stuff remains, like the friendships, the emotions, and the humorous anecdotes that have been told and retold so often at weddings and reunions that he and his teammates can recite the punch lines by heart. But football memories are difficult to pin down.

“I got down to watch the Griz play Portland State last year, and I ran into so many guys I played with,” Gragg says. “It’s like it was yesterday. You end up talking about this play or that play, and it’s like you never left. I think that says something about our group of guys.”

Gragg realizes too that he represents an era of Grizzly football that no longer feels familiar: the pre-national championship days. The year after he graduated, Dave Dickenson and Andy Larson helped forever change the expectations of Grizzly fans with a victory over Marshall in the I-AA national title game.

“I still felt like I was an integral part of it, the same way I feel like I’m a part of it now, fifteen years removed,” Gragg says. “When I played, the program was just starting to become the dynasty that it is now. So you realize you’ve contributed to an ongoing legacy.”

These days, Gragg stalks the sidelines, trying to build his own legacy. He says he hopes there is a little bit of Don Read, a little Steve Mariucci, and a touch of Dan Reeves in his coaching style. The Foxes have improved each of the three years Gragg’s been in charge, and Silverton won two games in the state playoffs in 2008.

“I still have a long way to go,” he says. “The way I look at it is, for twenty years I was responsible for getting myself ready to play on a weekly basis. Now, I’m responsible for getting one hundred kids ready. . . . I remember, my first week in the NFL, the other offensive linemen and I were watching film, and my position coach was criticizing me a bit. He asked me why I played the game. I said, ‘Because I love it.’ He told me, ‘Not anymore. Now it’s a job.’ I disagree with him. I still feel that way.”

Tuff Harris was seven years old, scraping up his knees on the dirt roads of St. Xavier, when he first started dreaming of an NFL career. He and his brother, Jay, would collect football cards and spend hours playing catch in front of his grandparents’ house.

“We grew up in a town of about thirty people, so there were no neighborhood kids to play with us,” Harris says. “I’d snap the ball and run, and he’d throw it to me, then we’d line up and do it again.”

Unlike so many American Indian kids he knew, basketball didn’t grab hold of his heart and refuse to let go. It was football—its speed, its strategy, and the ferocious beauty of the game—that called to him. Didn’t matter that there were only thirteen kids on his high school team in Colstrip his senior year. He was always one of the fastest players on the field, no matter who he lined up against. He decided he was going to ride that dream until it bucked him off, the same way he learned to break horses growing up.

Gragg prepares to block a Philadelphia Eagles opponent while playing for the San Francisco 49ers in 2002.

The reality of the NFL, however, is that sometimes talent and hard work aren’t enough to provide security. After a stellar four-year career as a defensive back with the Grizzlies, where he also was one of the most electric kick returners in the country, Harris signed with the Miami Dolphins as an undrafted free agent in 2007.

He didn’t play much, but learned plenty.

“As a kid, I always thought that if you were the best player, and the hardest worker, you’d make it every time,” Harris says. “But you realize that if a guy is getting paid, he’s going to play. It’s a business. It’s not always the coach’s decision whether you’re on the field or not. Even if you’re playing well and working hard, you never know how they’re crunching numbers in the front office. You can’t get caught up in that. It was an important lesson to learn for me.”

When the Dolphins cut Harris, he had a brief stint with the New Orleans Saints before getting cut again and signing with the Tennessee Titans. He made it on the active roster last year, and even saw some time in the AFC divisional playoff game against the Baltimore Ravens, but he knows he’ll be fighting for a roster spot once again when camp begins. It’s unlikely, however, that he’ll be competing against anyone with a similar off-season workout. Remember Rocky Balboa training to fight Ivan Drago by marching through the snow-capped mountains of Russia? Other than a brief vacation to attend the weddings of former teammates, that’s been Harris’ life in recent months.

“I’ve been doing all the training I possibly can,” Harris says. “I went to Wyoming with some family and did a lot of high-elevation running and lifting rocks and trees. You can really tell the difference up there. You really get lightheaded.”

Regardless of what happens to Harris the rest of his career, he already has made an impact back home on the Crow Reservation. When the Grizzlies sign American Indian players in the future, it will be, in part, because of Tuff Harris.

“I was always so focused on getting on the field and playing, I didn’t ever realize the importance of it,” Harris says. “To my knowledge, there’s never been a Crow or Cheyenne who has played in the NFL. I don’t really think about it until I come home, and then people are constantly coming up to me saying, ‘Talk to my son. Tell him what you’ve done.’ It’s kind of exploded on the reservation.

“Where I come from, all people care about is basketball. And it’s kind of sad in a way, but for some people, the biggest accomplishment in their life was winning a state championship. That’s the pinnacle of their vision. They could do that, and their lives would be complete. I’m trying to show that there is more than that.”

Before Colin Dow left Billings for college, his father passed on an important piece of advice. One that he would not soon forget.

If you want to have a good time at school, Jimmy Dow said, you have to meet a Butte guy, and then make him one of your best friends.

So when Dow got his dorm room assignment that fall, it seemed a little serendipitous that the guy across the hall was a free safety from Butte with a square jaw and hair so long it nearly touched his shoulders.

His name was Colt Anderson, and he and Dow were about to become as close as brothers.

“Once you set those things in motion, they’re pretty tough to stop,” Dow says. “As time went on, I realized how right my dad was. It’s crazy how close we’ve become. It’s funny, but I remember telling my mom that friends I made in high school I’d never forget and we’d always be real tight. She looked at me and said, ‘I hope you’re right.’ I can’t remember half those guys now. It’s the guys you meet in college, when you figure out who you’re going to be—that’s who you really are.”

| “ | It’s like it was yesterday. You end up talking about this play or that play, and it’s like you never left. I think that says something about our group of guys. | ” |

To bring this family story full circle, it’s essential to pause, one last time, in the present.

Anderson and Dow, who led the Grizzlies to the national championship game in 2008, spent the spring and summer preparing for their NFL careers. Both went into mini-camp green and hopeful, a sense of endless possibility in front of them. Neither was drafted, but both felt determined to prove they belonged. Anderson signed a three-year deal with the Minnesota Vikings and Dow a two-year deal with the Bengals—the same team where Scrafford began his NFL career.

Even though they were with different teams, hundreds of miles apart, it felt, in a way, like they were in it together. The business aspect of professional football had not yet sunk in. They talked virtually every day about their hopes and their fears, just like they did throughout college, on road trips, on float trips, and during the days and nights they worked together behind the bar at the Missoula Club.

“That’s kind of one of the things I learned talking to guys in the NFL,” Anderson says. “Montana is a little different from other schools. It’s kind of a big band of brothers. We’re able to talk to one another, root for one another, and that’s what I’ll always cherish about my time there.”

Dow, a 6-foot-4, 300-pound bear of a man during his time in Missoula, was a prankster and a joker throughout college—one of the few Grizzly players adept at cracking jokes to make others laugh. He was back home in Billings recently—working at a football camp with high school kids before getting ready to report to training camp with the Bengals—when he was struck by something.

No matter what happens next, he told himself, I’ve been blessed.

“I’ve always kind of thought that whatever you do in life, you better have fun with it,” Dow says. “Even when I’m holding a bag for high school campers to hit, I tell myself, ‘You remember how lucky you are to be playing football. To be twenty-three years old and playing football for a living is an amazing blessing.’”

Dow’s father passed away during his sophomore year at UM, and the emptiness he felt after his death was not easy to live with. But not long after the funeral, the owner of the Missoula Club, a friend of Jimmy Dow’s, asked Colin if he’d be interested in tending bar there during the off-season. A picture of his father from when he played at MSU-Billings already was on the wall, right by the front door. Occasionally patrons would look at the picture, then look at the bartender, and act like they’d just seen a ghost.

“I like to think of Montana as the biggest small town in America,” Dow says. “It’s that kind of that community, where people really know everybody’s history.”

Before long, Dow, Anderson, and Rob Schulte—another Grizzly player and “the third leg of our tripod,” according to Dow—were working at the bar, flipping burgers, and pouring drinks, listening to old stories about Grizzly lore and retelling some of their own.

And so when the bad news came down, when Dow learned from the Bengals medical staff that two vertebrae in his back were beginning to fuse together and three disks were bulging, that his NFL career was over before it had even begun, he knew his first phone call would be to Anderson.

“And then there was one,” was all Dow’s voice mail said, and even before he returned the call, Anderson understood what his friend meant. Dow’s football career was over.

“It’s something I’m still trying to deal with,” Dow says. “The hardest part for me, right now, is remembering how far I’ve come, and trying not to look at it as how far I didn’t go. I was there. I smelled it, I saw it, I touched it. I just couldn’t hold on.”

Dow made sure to pass along something else to Anderson when the two finally spoke: When you make the team, buy a couch big enough for me to sleep on. Because there will be a road trip planned for when you play your first NFL game.

For Dow and Anderson, just as it was for Scrafford and Gragg, for men like Tuff Harris, Dan Carpenter and Kroy Biermann, and for those who paved the way like Guy Bingham and Tim Hauck—Grizzly football is a brotherhood. Even when your own journey ends, the dream lives on in others, almost as if they were family.

Tennessee Titans defensive back Tuff Harris tackles a Steelers kick returner during a December 2008 game.

Then and Now:

Griz Nation To The ProsThere are ninety-five former Griz dating back to 1922 who have parlayed their college football success into careers in the professional football arena. Below is a breakdown of those players and the teams they signed with since 1960.

Please Note: *Signed as free agent; # Active at press time

John Lands, 1960, Indianapolis Warriors

Gary Schwertfeger, 1961, British Columbia Lions

Bob O’Billovich, 1962, Ottawa Rough Riders

Terry Dillon, 1963, Minnesota Vikings

Mike Tilleman, 1964, Chicago Bears

Bryan Magnuson, 1967, Washington Redskins

Dave Urie, 1969, Houston Oilers

Willie Postler, 1972, British Columbia Lions

Steve Okoniewski, 1972, Atlanta Falcons

Roy Robinson, 1972, Saskatchewan Roughriders

Barry Darrow, 1974, Cleveland Browns

Walt Brett, 1975, Atlanta Falcons (4th Round)

Ron Rosenberg, 1975, Cincinnati Bengals (13th Round)

Greg Harris, 1975, New York Jets

Doug Betters, 1977, Miami Dolphins

Terry Falcon, 1977, New England Patriots

Greg Anderson, 1979, Montreal

Tim Hook, 1979, Saskatchewan Roughriders

Carm Carteri, 1979, Ottawa Rough Riders

Guy Bingham, 1980, New York Jets (10th Round)

Pat Curry, 1982, Seattle Seahawks*

Rocky Klever, 1982, New York Jets (9th Round)

Rich Burtness, 1982, Dallas Cowboys (12th Round)

Mike Hagen, 1982, Seattle Seahawks*

Mickey Sutton, 1983, Pittsburgh Maulers*

Brian Salonen, 1984, Dallas Cowboys (10th Round)

Mike Rice, 1987, New York Jets (8th Round)

Brent Pease, 1987, Minnesota Vikings (11th Round)

Larry Clarkson, 1988, San Francisco 49ers (8th Round)

Pat Foster, 1988, Los Angeles Rams (9th Round)

Tim Hauck, 1989, New England Patriots*

Jay Fagan, 1989, Washington Redskins*

Kirk Scrafford, 1989, Cincinnati Bengals*

Matt Clark, 1990, British Columbia Lions

Mike Trevathan, 1990, British Columbia Lions

Brad Lebo, 1992, Cincinnati Bengals*

Sean Dorris, 1992, Houston Oilers*

Todd Ericson, 1994, Indianapolis Colts*

Carl Franks, 1994, Toronto Argonauts

Scott Gragg, 1995, New York Giants (2nd Round)

Shalon Baker, 1995, British Columbia Lions*

Marc Lamb, 1995, New York Jets*

Keith Burke, 1995, Ottawa Rough Riders

Dave Dickenson, 1996, Calgary Stampeders*

Blaine McElmurry, 1997, Houston Oilers*

Joe Douglass, 1997, New York Jets*

David Kempfert, 1997, Seattle Seahawks*

Jeff Zellick, 1997, New York Giants*

Jason Baker, 1998, Jacksonville Jaguars*

Jason Crebo, 1998, Buffalo Bills*

Brian Ah Yat, 1999, Winnipeg Blue Bombers*

Scott Curry, 1999, Green Bay Packers (6th Round)

Kris Heppner, 2000, Seattle Seahawks*

Dallas Neil, 2000, Atlanta Falcons*

Chase Raynock, 2000, New Orleans Saints*

Jeremy Watkins, 2000, New York Giants*

Jimmy Farris, 2001, San Francisco 49ers*

Leif Thorsen, 2001, British Columbia Lions (1st Round)

Thatcher Szalay, 2002, Cincinnati Bengals*

Calvin Coleman, 2002, New York Giants*

Drew Miller, 2002, Detroit Fury*

Etu Molden, 2002, Chicago Rush*

Spencer Frederick, 2002, New Orleans Saints*

Dylan McFarland, 2003, Buffalo Bills (7th Round)

Jon Skinner, 2003, San Diego Chargers*

Chris Snyder, 2003, Detroit Lions*

Justin Green, 2004, Baltimore Ravens (5th Round)#

Andy Petek, 2004, Hamilton Tiger Cats

Cory Procter, 2005, Detroit Lions*#

Craig Ochs, 2005, San Diego Chargers*

Levander Segars, 2005, Montreal Allouettes

Willie Walden, 2005, Kansas City Chiefs*

Trey Young, 2005, Calgary Stampeders#

Brad Rhoades, 2006, Tennessee Titans*

Tuff Harris, 2007, Miami Dolphins*#

Josh Swogger, 2007, Kansas City Chiefs*

Ryan Bagley, 2008, Saskatchewan Roughriders*

Kroy Biermann, 2008, Atlanta Falcons (5th Round)#

Cody Balogh, 2008, Chicago Bears*#

Dan Carpenter, 2008, Miami Dolphins*#

Lex Hilliard, 2008, Miami Dolphins (6th Round)#

Colin Dow, 2009, Cincinnati Bengals

Colt Anderson, 2009, Minnesota Vikings#

J.D. Quinn, 2009, Miami Dolphins

Cole Bergquist, 2009, Saskatchewan Roughriders#

Email Article

Email Article