HigherEducation

By Patia Stephens

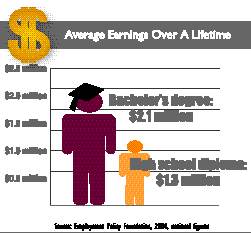

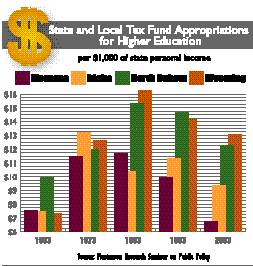

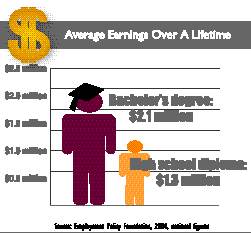

Across the country, tuition at public universities is skyrocketing to cover shortfalls in state funding. Some say high tuition is a fair trade for the increased earning power of a college graduate. Others point to the economic and social value of an educated citizenry, arguing that the state has a duty to support education. Still others suggest that education goes hand-in-hand with a growing economy—that it is a rising tide to lift all boats.

Tackling this vast subject, with its stacks of statistics, is not for the timid. And there is little agreement as to what can or should be done to remedy the situation. To simplify matters, we’ve decided to let the numbers and the players—alumni, students, parents, professors, administrators, and legislators—speak for themselves. What follows is a snapshot of how different people are dealing with the issue of rising costs and falling state support for higher education.

Alumna

Catherine B. earned two degrees from UM: a bachelor’s in political science in 1994 and a juris doctorate from the School of Law in 1997. As a Massachusetts resident paying out-of-state tuition, Catherine left UM owing $62,000 in federal loans. She went on to earn a graduate degree in international law from Georgetown University, adding another $40,000 in loan debt—half federal, half private. In 2001, Catherine consolidated her seven federal loans—one for each year of school—at a fixed interest rate of 8.25 percent.

“Everyone seemed to be telling me to consolidate, as making seven loan payments a month didn’t seem logical,” Catherine says. “I was never told that I could not reconsolidate in the future.”

Now, age thirty-one and working as an international trade analyst with the U.S. Department of Commerce in Washington, D.C., Catherine is repaying $625 a month toward her federal loans. A little over two years and $16,000 later, she owes only $750 less than she originally consolidated. The large debt and monthly payments have kept her from her dream of buying a home.

Catherine wrote a letter to the Montana Kaimin, UM’s student newspaper, last September, encouraging readers to support passage of H.R. 2505, the College Loan Assistance Act, which would change the 1965 law that now prohibits federal loans from being consolidated more than once.

“When I realized I was locked in at the highest interest rate and not paying the loan off after paying thousands of dollars in interest, I was very frustrated,” she says. “I began looking on the Web for other possible ideas. That’s when I came across the College Loan Assistance Act page and petition. I realized that my only option was changing the federal law, so that former students like myself do not have to pay thousands of dollars in interest and get nowhere.”

This reporter can relate. I graduated from UM in 2000 with a journalism degree and $26,558 in student loan debt. After making $8,263 in payments over the last three years, I still owe $23,255. I understand how amortization works—that I’m paying mostly interest right now and eventually my payments will start making a dent in the principal—but it’s still depressing. Especially when you consider that I’ll be paying $174 a month until the year 2021.

Why so long? I consolidated my loans in 2001, extending the repayment period because my initial $325-a-month payments under the ten-year plan were too high. I needed that extra cash to replace my dying ’88 Honda with a ’98 Subaru (a well-researched choice that came with an elusive $1,200 electrical problem). I consolidated at what then seemed like a low interest rate of 5.45 percent. Rates have since dropped even further, to 3.42 percent, but I’m stuck with this one.

My UM education will end up costing me some $50,000 in loan principal and interest. That doesn’t include the fifteen to twenty hours a week I worked during school, the forty-hour-a-week summer, winter, and spring breaks, or the numerous grants and scholarships I received.

But despite the fact that I can’t buy a house and am driving a six-year-old car, I consider it money extremely well spent. Getting my bachelor’s degree—at age thirty-two—was transformative. It strengthened my intellect, my self-confidence, my career potential, my quality of life. I am a different person. A better person.

Statistics support this: The better educated people are, the more likely they are to read, vote, enjoy good health, and earn a good living. The downside is that college graduates burdened by debt are more likely to postpone or forego buying homes, having children, and pursuing careers in the public interest.

Students

I have to wonder how many willing students never make it to college in the first place. After graduating from high school in Thompson Falls in 1985, it took me ten years—and five federal applications for financial aid—before I finally did. I didn’t understand the system and I was too busy trying to keep a roof over my head to figure it out.

I have to wonder how many willing students never make it to college in the first place. After graduating from high school in Thompson Falls in 1985, it took me ten years—and five federal applications for financial aid—before I finally did. I didn’t understand the system and I was too busy trying to keep a roof over my head to figure it out.

Then, in 1994, I received a form letter from Flathead Valley Community College asking why I had applied but never enrolled. The letter was signed by then-FVCC President David Beyer. I wrote him back a heartfelt letter expressing my desire to attend college and my frustration at never being awarded any grants or scholarships, despite making barely over minimum wage.

Beyer invited me to his office, where he explained to me that I would have to borrow money to get my foot in the door, and to stay in, although grants and scholarships would likely become more available after my first year. With his encouragement, and that of my boss and co-workers at the Whitefish Pilot, I enrolled in school in fall 1995. How many other Montanans are out there, wanting to get an education, but too afraid to go thousands of dollars into debt?

Thomas Crowley graduated from Anaconda High School in 2000. Now twenty-one and a senior at UM, he’s majoring in biochemistry with a minor in biology. Like the typical UM student who receives financial aid (68 percent overall), Crowley expects to owe about $17,500 by the time he graduates. “I’m nervous,” he says. “It’s kind of scary trying to start off life when you have a big debt over your head. It just doesn’t leave you much to fall back on.”

Crowley is a good student and a hard worker. He graduated third in his class from high school and has made the Dean’s List every semester at UM. He works eight to fifteen hours a week in a research lab on campus and spent last summer earning $22.50 an hour, nine hours a day, drilling test wells in Alaska. Because of family circumstances, he is paying his entire way through college. Recently he shouldered the costs of having his appendix removed.

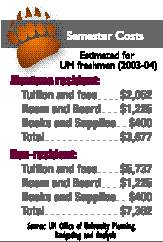

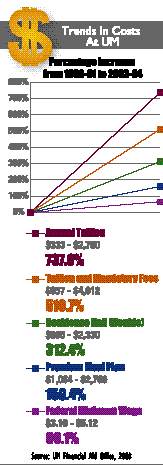

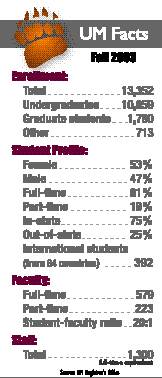

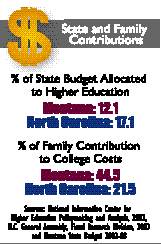

Where our parents’ generation could work their way through college, the new reality is that students must work and borrow their way through college. The reason? Ever-increasing tuition and fees, not just here in Montana, but across the country. Among our twenty peer institutions in the region—including universities in Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming—resident undergraduate tuition and fees have gone up an average of 71 percent since 1996. At UM, the increase has been 76 percent, making us the ninth most expensive school among our peers. When you consider the cost of tuition and fees as a proportion of median household income, we’re the most expensive school among twenty peer institutions.

To Crowley—whose father, a doctor, died when he was four—going into debt for his education is a gamble worth the risk. “I’m on a quest to better myself and to have a better future,” he says. “I’m also following in my father’s footsteps.” Crowley hopes to stay in Montana after graduation, but says he will leave if necessary to find a good-paying job.

To Crowley—whose father, a doctor, died when he was four—going into debt for his education is a gamble worth the risk. “I’m on a quest to better myself and to have a better future,” he says. “I’m also following in my father’s footsteps.” Crowley hopes to stay in Montana after graduation, but says he will leave if necessary to find a good-paying job.

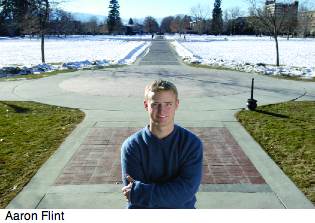

Another UM senior, Aaron Flint, echoes that sentiment. “I really want to stay in the state,” Flint says, “and I feel like I owe a lot, but if I had a big offer I couldn’t turn that down.” Flint has studied UM’s funding situation up close, from the vantage point of student government. A broadcast journalism major, he is the Republican president of the Associated Students of UM.

He thinks it can be valuable for Montana graduates to leave the state for work. “People say, ‘We’re just educating them and then they leave the state,’” he says. “But I think most of them will find a way back. They’re going to get their degrees and then go out to New York or Los Angeles and do wonderful things, and then they’re going to come back with these great experiences to bring back to Montana and build on.”

Flint also sees higher education as a great recruiter. “Something like 60 percent of out-of-state students stay in the state,” he says. “That’s what eastern Montana and the rest of the state is really hurting for. They need young professionals for their communities and the university system is key to that.”

As ASUM president, Flint has some ideas about the challenges facing UM and its students. “The biggest issue for us has been tuition increases,” Flint says.

“In the 1980s and ’90s, tuition has nearly tripled.” As a partial solution, he proposes reallocating the state’s budget, taking a slice of the pie from K-12 and giving it to higher education. “K-12 enrollment has declined while enrollment in higher education has increased,” he says, “but K-12 has had the political capital to get more money from the state while the university system’s funding stays flat.” (He would probably get an argument about that from the school districts and education groups who have filed suit against the state, claiming that state funding for K-12 is too low to give children the quality education guaranteed in the Montana Constitution.)

By “political capital,” Flint means the power of persuasion. “The university system needs to break out on its own more, with its own message, and not just join the line full of beggars,” he says. “I think the university system has a great sell for keeping young people in the state and creating opportunities for them. ... It’s putting higher education into context vs. the youth and senior citizens’ lobbies.”

By “political capital,” Flint means the power of persuasion. “The university system needs to break out on its own more, with its own message, and not just join the line full of beggars,” he says. “I think the university system has a great sell for keeping young people in the state and creating opportunities for them. ... It’s putting higher education into context vs. the youth and senior citizens’ lobbies.”

Flint, who is helping to pay his way through school with membership in the National Guard and ROTC, also thinks it’s important to boost the state’s budget. “Some people think we need to increase the tax rate and some think we need to increase the tax base,” he says. “I’m one of those supporting increasing the tax base. I think too often people get focused on increasing the tax rate.”

Flint would like to see the tax base increased by creating jobs in the state’s traditional natural resource-based industries along with newer, high-tech industries. He believes that mining and other extractive jobs bring big bucks to state workers, while technology programs like NASA’s Earth Observing System Project at UM also have the potential to create real revenue. Flint also appeals for a balance between a well-rounded liberal arts education and a more jobs-focused curriculum.

“Nurses are needed around the state, plumbers .... There’s always going to be jobs needed in the state,” he says. “Back in Glasgow, when I go visit, the people running the businesses on Main Street are UM graduates that got traditional liberal arts or business educations.”

Parent

Parent

Garth and Vicki Ferro of Helena have four children. The oldest is Kelsey, a sophomore in anthropology at UM-Missoula and a third-generation UM student. Garth’s father, John O. Ferro, graduated in 1958 with a degree in business administration; Garth earned a bachelor’s degree in business management in 1985 and a master of business administration degree in 2000.

“The cost of attendance per year is about $14,000 now,” Garth Ferro says, “and that’s how much it cost for my whole four-year degree.” Although Vicki has recently graduated from the Helena College of Technology and gone to work, she initially was a stay-at-home mom. Raising four children on Garth’s single salary made it impossible to put money aside for college. “My kids wanted to eat, so no, we didn’t save anything,” he says.

Kelsey’s education is being paid for with a combination of her parent’s salaries, her own part-time job, some help from her grandparents, and federal PLUS loans. Garth expects to owe about $15,000 in PLUS loans by the time Kelsey graduates. Multiply that times four kids, and he’s looking at owing some $60,000.

Nationally, tuition and fees take 9.1 percent of the average family’s income; in Montana, they take 12.75 percent. But Garth, who works for the Student Assistance Foundation of Montana, a nonprofit organization that helps students finance their educations, maintains a positive outlook.

Nationally, tuition and fees take 9.1 percent of the average family’s income; in Montana, they take 12.75 percent. But Garth, who works for the Student Assistance Foundation of Montana, a nonprofit organization that helps students finance their educations, maintains a positive outlook.

“I have time on my side,” he says. “I’m only forty-two, so that helps. I don’t look at it as a sacrifice. I look at it as an investment in Kelsey’s future, because it’s going to make her a better person and a better contributor to society.”

Garth says that by getting educated about your options and maintaining good communication with your child, paying for college is doable, if not easy. “Statewide, there aren’t a lot of resources to work with and the university system is doing a good job with what they have to work with,” he says. “I believe very strongly that here in Montana we have an excellent higher education system.”

Financial Aid Director

Financial Aid Director

When Mick Hanson graduated from UM in 1965, he had no debt and enough credit to buy a brand-new Pontiac GTO. Hanson, now UM’s financial aid director, tells me about this sweet ’65 GTO, which he still has, while I sit in his office shaking my head in envy.

Hanson then hands me a chart showing trends in costs at UM. It compares UM costs with the federal minimum wage twenty years ago and now. My jaw drops when I get to the punch line: If the federal minimum wage had kept pace with UM tuition, minimum wage would be $22.87 an hour instead of the current $5.15. This was the answer I needed when well-meaning relatives said to me, “I worked my way through college. Why can’t you?”

Another suggestion I heard was to make good grades so that I could get scholarships. I tried to explain that I did make good grades and I did get scholarships, but they were just drops in the bucket. Although every drop helps, it was frustrating to spend hours filling out scholarship applications, writing essays, and gathering letters of recommendation only to receive a few hundred dollars, if I was lucky.

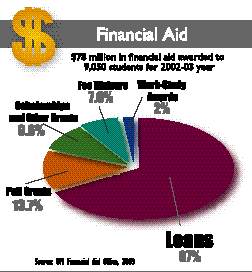

The good news, according to Hanson, is that in recent years scholarship awards have increased and loans as a percentage of financial aid packages have decreased. The bad news is that loans as a percentage of total financial aid are much higher than the national average of 58 percent. In Montana, which has the lowest U.S. median household income of all states but West Virginia, that means graduates are entering the workforce with a double handicap: greater loan debt than their national peers and less income with which to pay off those loans.

Faculty member

In case you’re wondering, UM faculty and staff aren’t reaping the rewards of higher tuition. Wages, already well behind national averages, are frozen for the current biennium. “Our salaries are falling further and further behind what’s paid at our peer institutions,” says economics Professor Kay Unger. “When I go to professional meetings, I am loathe to admit how much I make. It’s embarrassing.”

In case you’re wondering, UM faculty and staff aren’t reaping the rewards of higher tuition. Wages, already well behind national averages, are frozen for the current biennium. “Our salaries are falling further and further behind what’s paid at our peer institutions,” says economics Professor Kay Unger. “When I go to professional meetings, I am loathe to admit how much I make. It’s embarrassing.”

For the 2002-03 year, UM faculty earned an average of $58,959, while their colleagues at national, public doctoral universities earned an average of $70,357. So in theory, a UM professor could get an $11,000 raise just by leaving the state. Why do they stay?

“This is my home,” says Unger, who has taught at UM since 1978. “Once you sink roots into a community, it’s difficult to leave.” However, low salaries make it hard for UM to attract new faculty members, Unger says, especially women and minorities, who are valuable commodities in the academic job market. “Montana is competing with all the other universities that are hiring,” she says, “and if our salaries are low, then we cannot attract the best people.”

Falling state support and rising tuition are not only “bad for faculty salaries, but they are also bad for the state of Montana,” Unger says. “What we end up with is that, at the margin, there will be students who are qualified and capable of going to college and getting a good job who don’t get to go because they can’t afford it. Or they leave college with an enormous indebtedness ... a $50,000 or $60,000 student loan debt. It’s like coming out of college with a mortgage.”

Falling state support and rising tuition are not only “bad for faculty salaries, but they are also bad for the state of Montana,” Unger says. “What we end up with is that, at the margin, there will be students who are qualified and capable of going to college and getting a good job who don’t get to go because they can’t afford it. Or they leave college with an enormous indebtedness ... a $50,000 or $60,000 student loan debt. It’s like coming out of college with a mortgage.”

More immediately, Unger sees the effects in crowded classrooms. “I’ve got 250 students in an introductory economics class, and I can’t even see the people in the back row,” she says. “I don’t know them if I pass them on the street. It’s not the best way to teach, but that’s all we have the resources for.”

A former president of the UM Faculty Senate, Unger represented faculty as a lobbyist during the 2001 Legislature in Helena. “I drove over that [McDonald] pass twice a week,” she says. “I think it’s important to have faculty members over there .... The students [lobbyists] are incredibly passionate, very hard-working, and bright, but it’s as if the legislators don’t take them seriously because they’re students, they’re not taxpayers.

“It ought to be that the entire university community goes in as a group—faculty, students, administrators—and presents the same message,” she says. “The Legislature does indeed understand what’s going on. It isn’t that they don’t understand, it’s that they choose not to see. It’s denial.”

Chief financial officer

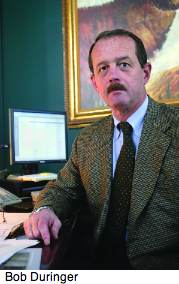

Bob Duringer, UM’s vice president for administration and finance, says the faculty-staff wage freeze is the only thing keeping the university solvent. “In the next biennium, we’re going to have to give a pay raise,” Duringer says, “so the state is either going to have to fulfill its responsibility or it will be carried on the backs of the students.”

Bob Duringer, UM’s vice president for administration and finance, says the faculty-staff wage freeze is the only thing keeping the university solvent. “In the next biennium, we’re going to have to give a pay raise,” Duringer says, “so the state is either going to have to fulfill its responsibility or it will be carried on the backs of the students.”

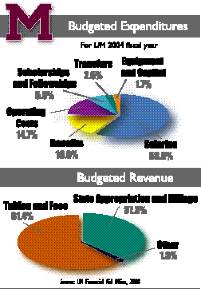

So, where is the money going?

While the amount of funding UM receives from the state has held steady for the past ten years, its expenses have not. It has more students, as well as bigger bills for electricity, insurance, employee health care, and technology needs such as computers.

Ten years ago, two-thirds of UM’s budget came from state appropriations and the other third from tuition. Now the situation is reversed: tuition makes up two-thirds and state appropriations one-third. In 1994, the state subsidy per resident student was $4,394; in 2003, it was $4,052.

“We have more students and we’re getting less money for them,” Duringer says. “Our state subsidy is one of the lowest per student, and yet we keep the doors open. Analysis shows we are among the most efficient, if not the most efficient.”

While the number one side effect of lowered state funding is higher tuition, Duringer says, number two is suffering faculty/staff salaries. “UM’s average faculty/staff salary is three-quarters of the national average,” he says. “It makes it very difficult to recruit good people.”

Side effect number three? A neglected physical infrastructure. “We’re not getting enough to maintain the campus—roof repair, windows, the steam line ....” The list goes on.

A businessman at heart, Duringer has a few potential solutions up his sleeve: Create charter universities. Establish a contract between the Legislature and the university agreeing on certain levels of student retention, graduation rates and other measures of quality, in exchange for a specified level of funding.

Run the university like a business. “Let us invest money in safe, but profitable ways,” Duringer says. “The more the state lets us run this like a private business, the better we can respond to changing market conditions.” Duringer was key in forging a marketing agreement with Coca-Cola, which has brought more than $1 million to UM.

Run the university like a business. “Let us invest money in safe, but profitable ways,” Duringer says. “The more the state lets us run this like a private business, the better we can respond to changing market conditions.” Duringer was key in forging a marketing agreement with Coca-Cola, which has brought more than $1 million to UM.

Reduce expenses by limiting enrollment. “Washington State and Oregon capped enrollment,” he says. It’s the flip side of cutting costs by cutting services, which Duringer says is deadly: “You don’t want to lower quality standards.”

President

During his thirteen years at the helm of UM, President George Dennison has tried a number of approaches to keep the books balanced, including proposing a 4 percent limited sales tax to the 2001 Legislature.

“It was a visitors’ tax,” Dennison says. “Don’t call it a sales tax. Residents would be exempt. It would affect only visitors to the state, allowing those who use the infrastructure to make a contribution. It would generate $100 million in revenue at first, increasing with the Lewis and Clark bicentennial.”

Although the measure was defeated, Dennison hopes to see it resurface in the next legislature. Last October, Dennison tried another tack with the state Board of Regents, suggesting options such as imposing a property or sales tax in communities with schools, attracting more out-of-state students, and limiting enrollment. Dennison also is a strong advocate for bringing more national research grants to Montana. In 2003, UM funneled $60 million in research money into the state. To put that in perspective, $20.4 million was generated in research grants in 1994.

“I think there is no question about the relationship between a healthy and vibrant higher education system and economic development in Montana,” he says. “The question is, how do we resolve this chicken-and-egg sequence here?”

Dennison outlines a societal shift in the perception of higher education as a public vs. a private benefit. Where once we invested in higher education, believing it served the nation to have a well-educated citizenry, in the 1970s people began to see education as something that primarily benefited individuals.

As expenses grow in areas such as health care and prisons, higher education falls lower on the priority list. “If higher education isn’t funded, nobody’s going to die,” he says, “except the society, which will lose its responsiveness and competitiveness in the twenty-first century. If American civilization is going to die, that will be why.”

Beyond new taxes, Dennison says there is no shortage of ways to increase revenue. As one example, he describes an idea once proposed by former U.S. senator and presidential candidate Bill Bradley for use of some of the so-called “peace dividend” at the end of the Cold War: a revolving account assuring every American the money to pay for college—but only for college—in the form of loans. The loans would be paid back toward the end of a person’s lifetime rather than directly after college, when graduates are starting careers, families, and home ownership. “Maybe a new approach is worth thinking about,” Dennison says. “We need something that breaks this cycle, and that will require thinking outside the box.”

Montana legislators

Republican legislators John Bohlinger and John Witt share first names, political parties, and an abiding concern for the state of Montana and its people, but when it comes to funding higher education, they often vote at odds with each other.

Republican legislators John Bohlinger and John Witt share first names, political parties, and an abiding concern for the state of Montana and its people, but when it comes to funding higher education, they often vote at odds with each other.

Bohlinger, a state senator from Billings, is one of Montana’s biggest legislative supporters of higher education. “I really feel that if we don’t put more money into higher education, we will not achieve this goal of a stronger economy,” he says.

Witt, state representative from Carter, says higher education gets its fair share of the pie, however meager it may be. “Our responsibility as a legislator is to make sure we arrive at a balance in the best interest of everyone’s needs,” he says. “I think that education today is a bargain,” Witt continues. “I think that the typical student will probably do something that costs him more a very short time after graduation than his whole education cost him.” As an example, Witt says, “Maybe he’s guaranteed some fancy job somewhere and goes out and spends $40,000 on a car.

“I definitely want our kids to be educated and I think we are doing a fair job of that,” Witt says. “Can we do better? Of course we can, but as we do better the costs go up.”

Bohlinger believes current public policy shortchanges higher education—and Montana residents. “In a de facto way, we’re saying that higher education is only available to those who can afford it,” Bohlinger says. “I think that’s shameful. There’s a moral issue here. It’s discriminatory to say that only those who can afford to go to college can have that opportunity. Also, our Constitution talks about how we value education.”

Witt isn’t opposed to giving higher education more money—if more money is available. Hoping to increase Montana’s revenues, he introduced H.B. 757 in the 2003 Montana Legislature, which would have allowed creation of special gaming and entertainment districts. Supporters envisioned Butte as one potential district where visitors would flock for Vegas-style gambling and Branson-style music and plays.

“I’m not anti-education and I’m not anti-higher education,” Witt says. “I’ve gone that mile to try to help. … People are opposed to timber harvests, they’re opposed to mining … they’re opposed to the programs that generate revenue.”

Bohlinger says, “The question is, how do we grow our economy?” He has worked to increase both the tax base and the tax rate. To create a more business-friendly climate, he supported measures that reduced taxes on equipment and machinery from a high of 12 percent to the current 3 percent, a rate competitive with neighboring states. He also introduced a sales tax in the last session, and supported proposals to tax soda and gambling, although all were defeated. “We were so desperate, I was willing to support them,” Bohlinger says.

Witt also supports a sales tax. “If people want to honestly fund education, we need a sales tax,” he says. “I do support a sales tax. We can no longer fund education on the backs of property taxpayers.” While a number of sales tax proposals have been voted down over the years, Witt believes his colleagues in the Legislature are becoming more receptive to the idea.

However, he says many share a distrust of the Montana University System. “I think there needs to be more accountability in the university system,” Witt says. “I’m not sure we understand where all the money goes.”

To address this oft-heard complaint, the university system has worked to provide more information and become more scrutable. In January 2003, UM-Missoula and Montana State University-Bozeman teamed up to publish “Montana Invests,” a booklet detailing higher education’s statewide economic impact. One highlight of the report was that the university system annually generates more than $480 million in statewide spending, including $300 million from out-of-state sources like research grants and students and their visiting families.

For Witt, the suspicion remains. “They’re always good about providing us information, but I’m not sure we always hear the whole story,” he says. “We just hear the side they want us to hear.”

Bohlinger thinks Montana’s universities and colleges are a vital key to the state’s success. “Clearly, the opportunity lies to those who are educated,” he says. “Whether it’s a university degree or going to one of our community colleges or technical schools, these are skills that will make people employable and provide long-term economic benefit to them and their families and the state.

“We need educated people,” Bohlinger continues. “To run the farm, the ranch, requires an educated person. It’s not just putting the cows out in the pasture any more, or dropping seeds in the ground. These are high-tech jobs today. We need an educated workforce.”

In the end, Witt says, it’s all about making Montana stronger. “I may come off as anti-education to some people, but I wouldn’t be in the Legislature if I wasn’t working for the benefit of all the people,” he says. “We represent a district, but we also represent all Montanans.”

Bohlinger concludes, “When the Legislature meets in 2005, we’ve got to turn over those stones again to see if we can find some money. If we want to improve our economy, we have to invest in our educational system.”

North Carolina legislator

North Carolina is one state that has reaped the rewards of investing in its educational system. Tony Rand, state senate majority leader from North Carolina, couldn’t agree more—and he’s seen it in action. The University of North Carolina is the oldest state-supported institution in the United States, founded in 1789 on a constitution that says education shall be free so much as practicable.

Rand, a Democrat with two degrees from UNC, says the state’s university system, with its long-standing tradition of high funding and low tuition, has helped ease the state through a rough transition from its traditional industries—tobacco, textiles, and furniture—to a scientific- and technology-based economy.

Rand, a Democrat with two degrees from UNC, says the state’s university system, with its long-standing tradition of high funding and low tuition, has helped ease the state through a rough transition from its traditional industries—tobacco, textiles, and furniture—to a scientific- and technology-based economy.

“Higher education has been the cornerstone of our economic rebirth,” Rand says. “What has kept our financial ship afloat is the Research Triangle—which is a direct tribute to our university system—along with the great financial markets in Charlotte, and the Piedmont Triad area, which also has a strong higher education presence.”

The 7,000-acre Research Triangle Park—located near Duke University in Durham, UNC at Chapel Hill, and North Carolina State University in Raleigh—is a cutting-edge center for research and development, home to more than a hundred organizations doing work in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, information technology, and many other fields. More than 38,000 people hold full-time jobs with RTP companies such as IBM, GlaxoSmithKline, Nortel Networks, and Cisco Systems.

Similarly, the twelve-county Piedmont Triad—encompassing the cities of Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and High Point—markets itself as an ideal location for businesses ranging from health care and biotech to manufacturing and distribution. Sara Lee, American Express, and United Parcel Service are among the biggest employers in the Triad, which has become one of the country’s hottest regions for business real estate. The area’s higher education institutions, including UNC Greensboro, A&T State University, and Wake Forest University, provide a skilled workforce for companies looking to relocate.

“The governor of Tennessee was asked, if he could have one industry from North Carolina, what would it be? And he said, ‘The university system,’” Rand says.

Rand, whose great-grandfather graduated from UNC in 1848, credits the university system’s—and the state’s—success to “enlightened leadership who believed in and were great supporters of education. “There’s no more precious resource we have in North Carolina than our university system,” he says. “I think that defines us as a state. It is ingrained in us, almost as a matter of faith, that the university has to be protected and nurtured.”

What do you think? Do any of these ideas appeal to you? Do you have some suggestions of your own? Continue the discussion in the Montanan Chatroom at www.themontanan.us.

Patia Stephens survived three semesters of algebra to get her journalism degree from UM in 2000. Although she hates math, she climbed a mountain of statistics to write this story because she believes in the power of higher education.

Patia Stephens survived three semesters of algebra to get her journalism degree from UM in 2000. Although she hates math, she climbed a mountain of statistics to write this story because she believes in the power of higher education.

![]() Discuss this article in Montanan Chat now!

Discuss this article in Montanan Chat now!