A Native Journey

Story By Ryan Newhouse

We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return…

- Henry David Thoreau, Walking

When Klaus Lackschewitz was a child living in Germany, he came to his father with a flower he had picked in the forest and asked what it was. His father, a forester, replied, “Das ist eine Pyrola mein kind.” Fifty years later Klaus again stood over a delicate, singular stem of pink flowers, the Pyrola (wintergreen). He had found it on one of his many walks in the Bitterroot Mountains in southwest Montana.

When Klaus Lackschewitz was a child living in Germany, he came to his father with a flower he had picked in the forest and asked what it was. His father, a forester, replied, “Das ist eine Pyrola mein kind.” Fifty years later Klaus again stood over a delicate, singular stem of pink flowers, the Pyrola (wintergreen). He had found it on one of his many walks in the Bitterroot Mountains in southwest Montana.

Lackschewitz discovered other flora in the Bitterroots, two of which were named for him—Agroseris lackschewitzii and Lesquerella klausii. And the U.S. Forest Service recognized his keen eye for native flora with the publication of his guidebook, Vascular Plants of West Central Montana in 1991. But this is not why a 2,400-pound quartzite rock, taken from the lower Blackfoot River, now sits near the Natural Sciences building on UM’s campus. A plaque on the commemorative rock reads, “Klaus Lackschewitz and Sherman Preece: Men of vision who created this native plant garden and generously shared their knowledge of Montana plants.” Lackschewitz and his wife, Gertrud, moved to Missoula in 1960 when Gertrud was hired to teach in the University’s foreign language department. A former German soldier and Russian POW, Lackschewitz had been trained as a botanist in the Baltics. A few years later, Sherman Preece, chair of UM’s botany department, asked Lackschewitz to teach botany courses.

On a Saturday morning in May 1967, the two professors began planting the native gardens that surround UM’s Natural Sciences annex and greenhouse. They envisioned the gardens as a new teaching tool that would provide a hands-on experience for students.

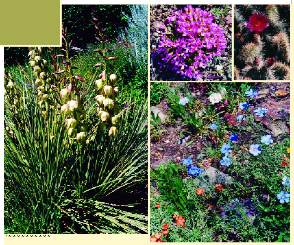

After subsequent plantings by Lackschewitz, Preece, and a handful of students and volunteers, a garden of Lackschewitz’s design had been realized. It represented more than 400 plants found in Montana, east and west of the Continental Divide—from landscapes such as the xeric steppe and bunchgrass prairie, to the wet meadows, mesic coniferous forest, and alpine areas, which were Lackschewitz’s specialty. The structural rocks for the garden were taken from a cut on Mount Sentinel and transported in an old Ford truck that Preece had until he died in 1993. Lackschewitz continued to care for the gardens until his retirement from the University in 1976.

The gardens were dormant for more than ten years after Lackschewitz’s retirement. In 1989 members of the Clark Fork chapter of the Montana Native Plant Society (MNPS) decided to continue what the professors had started. Leading the project were Jean Parker, a retired speech and hearing therapist, and Jean Pfeiffer, a retired medical technologist whose husband, Burt Pfeiffer, taught zoology courses at the University. Both women had accompanied Lackschewitz on his plant-gathering excursions to places like the Bitterroots, Anaconda Pintlers, the Crazies, and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. “He knew plants,” Pfeiffer recalled of Lackschewitz.

There is something in the mountain air that feeds the spirit and inspires.*

These days, Parker and Pfeiffer’s trips are less rugged. Weather permitting, they spend their Wednesday afternoons tending their designated sections of the native gardens. Parker is known as the “fern lady.” Her section is the ground cover on the east side of the annex, under the aspens, cedar, spruce, grand fir, hemlock, and larch. A small gravel path winds beside her garden. The path is roughly fifty-five strides long and meant to be taken slowly. A low-hanging red cedar branch deters a fast pace. The small grove of aspens on the north end of the gravel path were taken from the Rattlesnake area, and the aspens and edging rocks on the south end were transplanted from a private ranch on Kootenai Creek in the Bitterroot Valley.

The MNPS believes that plants should no longer be removed from the wild because of possible destruction of habitats and plants. The native gardens now act as a preserve, and plants produced from it can be bought and sold at the society’s annual plant sale. Every year Pfeiffer is there, selling the plants with her soil-toughened hands.

Living much out of doors . . . will no doubt produce a certain roughness of character—will cause a thicker cuticle to grow over some of the finer qualities of our nature, as on the face and hand.

Most of the plants in the native gardens are living outside their natural zones and landscapes, which creates more work for those who care for them. Both Parker and Pfeiffer thought they were going to start weaving and knitting when they retired, but instead they are stitching together a legacy left by Lackschewitz and Preece that was nearly forgotten by neglect. But they are not alone. On average, eight volunteers spend their Wednesday afternoons in the native gardens and additional support has been given by the University’s Physical Plant and Division of Biological Sciences, mostly in the form of tools, soils, and storage sheds.

A town [or University] is saved, not more by the righteous men in it than by the woods and swamps that surround it.

Perhaps the best lending pair of hands come from Kelly Chadwick, garden supervisor for the University Center and a founding member of the MNPS. Chadwick’s involvement with the native gardens is rooted in love for the plants themselves. Her official job is to tend to the gardens in and around the University Center, but in her spare time she has been building the lowland moist forest area east of the Natural Sciences annex. Four years ago, that area was only a patch of grass with a few Norway maple trees. Although the trees have remained, they are now accompanied by lady and sword ferns, small cedars, and a stone walkway that splits from the gravel path. “The maples are dying, and we’re hoping that when they go we can replace them with some native trees,” Chadwick explains. Chadwick assisted the MNPS with installing an interpretive map of the gardens on campus and with designing a brochure that includes a list of plants in the gardens that had been collected and recorded by Lewis and Clark in what is now the state of Montana.

Eastward I go only by force; but westward I go free.

Lewis and Clark collected almost all of those plants in July 1806, forty-five years before Henry David Thoreau delivered a speech titled The Wild to the Concord Lyceum. That speech would later become Walking, which was not published until six months after his death in 1862. In his essay, Thoreau looked toward the West, not as a great expanse of open space, but as an expanse for the human spirit: “We go eastward to realize history and . . . we go westward as into the future, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure.” But in the short 140 years since Thoreau’s ideas were notable, it has become necessary to protect the West from expansion and encroachment. Even in less than forty years, the purpose of the native gardens has changed from being a teaching tool to fulfilling the need to preserve the plants and their histories. The garden’s worth as a tool is now outshone by its priceless bounty as a museum.

Ryan Newhouse is a freelance writer and a UM graduate student in environmental studies. His work has appeared in several magazines and the anthology Foreign Ground: Travelers‚ Tales.

Ryan Newhouse is a freelance writer and a UM graduate student in environmental studies. His work has appeared in several magazines and the anthology Foreign Ground: Travelers‚ Tales.

* All passages taken from Thoreau’s essay, Walking 1862.

![]() Discuss this article in Montanan Chat now!

Discuss this article in Montanan Chat now!