An Extraordinary Life

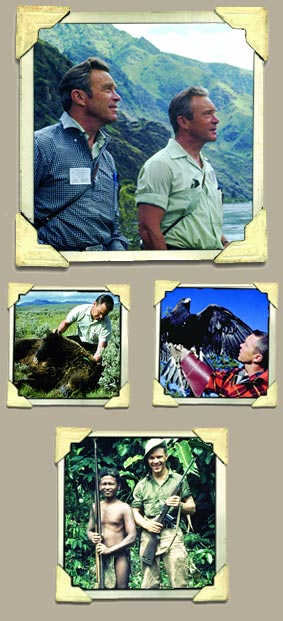

John Craighead studied many forms of wildlife, including human beings.

by Vince Devlin

Top

Photo below by S. Gebhards; |

||

“It all started in the 1930s with two teenage boys and a hawk named Comet.

The father of the boys—twin brothers—took them on long hikes every weekend along the Potomac River, pointing out various species of plants and birds.

The twins had already talked their father into letting them take a barred owl home, which fueled an interest in falconry. “The sport of kings,” says John Craighead, one of the twins. “We learned the American Cooper’s hawk had never been tamed or trained.” So they found one and did so.

“It takes quite a bit of time manning (taming) them and introducing them to the prey that you want to fly them at,” Craighead says. “It’s natural for birds of prey to kill—in fact, they have to kill every day to survive—and falconry is simply channeling the bird’s killing instinct.”

Comet was an extremely aggressive female, able to take down prey as large as a cottontail rabbit. “A cottontail is quite large for a female Cooper’s hawk,” Craighead says. “Normally a female Cooper’s hawk wouldn’t kill prey that large, and to fly a trained one at a cottontail rabbit was quite a struggle.”

As John and brother Frank tamed, trained and bonded with Comet, they kept a diary of their project and took photographs. Then one day, the teenagers marched into the offices of National Geographic magazine and asked to see the chairman. We have written a story about our adventures with hawks, they told a secretary. And we have pictures. The chairman, himself a twin, was curious about the two boys down in the magazine’s lobby. He invited them up to his office.

After hearing them out he bought their stories and pictures, and the careers of two of America’s foremost wildlife biologists and internationally known grizzly bear researchers were born.

An Endowed Chair

Today UM—John J. Craighead’s academic home for a quarter century—is $470,000 away from being able to establish the John J. Craighead Chair in Wildlife Biology.

“With this, we can go after a big name to jump-start the research he conducted,” says Daniel Pletscher, professor and director of the wildlife biology program. Pletscher points to another chair at UM endowed by the Boone & Crockett Club for a professor of wildlife conservation, currently held by Jack Ward Thomas, former chief of the U.S. Forest Service. “That’s the kind of person we can attract,” he says. “John Craighead was an incredible pioneer in his field. It’s a name everybody recognizes and respects.”

Craighead headed the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit during his twenty-five-year association with the University. The endowed chair requires a total of $2.5 million and UM has collected just over $1 million of that, according to John Scibek, director of planned giving at the UM Foundation. Major contributors include the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the M.J. Murdock Trust, WSB Partnership, the R.K. Mellon Foundation, Bonnie Snavely, and an anonymous donor.

The school needs additional donations to make the chair a reality because two $500,000 challenge grants wait in the wings. The first kicks in when $1.5 million has been raised, which will automatically trigger the second, which takes effect when the $2 million mark is hit. The UM Foundation and the University have until June 30th to get it done.

| |

|

|

| |

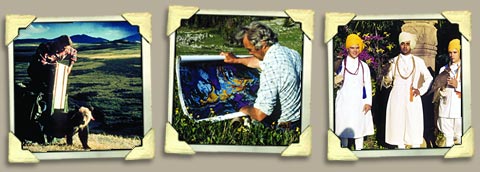

John releases a grizzly on left; in the middle he looks at a satellite-generated map that shows natural plant communities. The Craigheads were pioneers in the use of imagery of this kind in their research. right, John and Frank with the prince. |

|

| |

|

|

Grizzlies and Yellowstone

Most Americans know the Craigheads for their pioneering research on grizzlies in Yellowstone National Park from 1959 to 1971. A series of National Geographic television specials took their science into the living rooms of millions of ordinary people.

“The grizzly was not protected and we were able to get it classified as a threatened species,” John Craighead says. “Practically nothing was known about it, its life history, and even less about grizzly populations. It was obvious if we were going to save the grizzly we had to know a lot more about its biology. At what age are females able to reproduce? How many young did they have in a litter? How long were the cubs kept before they weaned them? What was the mortality rate of the young, and what caused the mortality?

“It was obvious the grizzly needed a lot of wilderness habitat. So to protect the grizzly, we had to protect wilderness and increase designated areas classified as wilderness.”

Learning what the bears ate was important and could only be accomplished by observation and analyzing feces. “My brother and I hit on the idea of placing a radio collar on them so we could locate and observe them whenever we wanted to, instead of relying on chance,” Craighead says. “This radio tracking was so successful that within a few years on all kinds of animals all over the world, scientists were placing radios on them. It made a tremendous difference. It probably increased the observation, I’d have to guess, by at least fifty-fold. There was just no comparison to how much you could learn when you had the radio.”

It was all ground-breaking science. The brothers had to develop methods to immobilize the bears in order to attach the tracking devices and ways to gauge their ages to aid their research.

“We tested a lot of things and finally got several that worked well and were safe,” Craighead remembers. “It would have been easy to kill a bear by giving it too heavy a dose. We had to approach it slowly and carefully and relate the dosage to the weight of the animal. At first that meant capturing them, but in time we could judge the weight pretty accurately. That meant we could just shoot them with the propulsive dart, which negated the need to trap them.”

The Craigheads worked out a system of determining bears’ ages by sectioning a pre-molar, an important part of their studies. “This enabled us to determine the age when females first bred and over time also told us how long females continued to reproduce,” he says. “One of the most interesting things was the grizzly had always been considered a loner, but we found they were social animals. When they aggregated to feed they established a social hierarchy with an alpha male at the top, and then subordinate males and females. It was interesting that the alpha male didn’t monopolize the breeding. He spent more time defending his status in the hierarchy. The other large males did most of the breeding.”

As the Craigheads learned more about the grizzly, so did the nation. The popular National Geographic television specials deftly combined science with a sense of adventure. The research was a family affair, and both twins brought their wives and children to Yellowstone, where TV cameras followed them at work and the children at play. Reminded of a scene where the Craighead children were shown swinging out over a cliff on a rope and plunging into a pool of water far below at Upper Falls, Craighead can’t help but laugh. “We caught hell for doing that from the (park) superintendent,” he recalls. “He thought that was a pretty bad place to put a rope.”

It wasn’t the only time the twins knocked heads with park honchos. When Yellowstone officials decided to close the dumps where grizzlies gathered each spring to feed, the Craigheads warned that the dumps had become part of the bears’ ecosystem. They said the dumps should be phased out. They cautioned that the bears, coming out of hibernation, would likely look for food elsewhere. That would probably take them closer to places occupied by humans and could result in danger to tourists and the possible need to euthanize the bears. The controversy that followed ended the Craigheads’ Yellowstone research.

“And,” notes Pletscher, “they were eventually proven right.”

An Indian Prince

The letter arrived from India, from Prince Dharmakumarsinhji. The prince, a falconer himself, had read John and Frank Craighead’s article about hawks in National Geographic. The twins wrote him back, starting a correspondence that eventually led to a trip to America by the prince—and an invitation to India for the young Craigheads.

“He was extremely intelligent and well-educated,” John Craighead says. “He was especially interested in co-education. In those times, Indian women, they didn’t even bother educating them.”

The Craigheads took the prince—they called him “Bapa”—to several universities back East, and also on a weekend trip on the Potomac. “My sister and her friends came along, and Bapa was amazed at what American young women could do,” Craighead says. “They could swim the rapids, paddle canoes, do most things the men did.”

In 1940 the Craigheads traveled to India. “He put us up like royalty,” Craighead says. “Every single day at dawn we would get up and go fly the hawks and falcons, or trap some. We’d hunt with the birds all morning, return for an afternoon siesta, then go out again until dusk. When we weren’t flying the falcons we’d hunt. Quail, partridges, antelope, wild boar.”

The Craigheads adopted the dress of their hosts, turbans and all. Their India adventure included a trip across the country to attend the three-day-long wedding of the prince’s brother and hunting trips where cheetahs—trained the same way falcons were—took down black buck antelope. “The cheetahs learned they’d be fed, so they’d make a kill and allow the handlers to move in,” Craighead says. “You put a hood on it right away, cut off a leg to give to the cheetah, and take the rest back to the palace to eat.”

The prince and his brother had a dozen falcons apiece and a dozen men each to handle them all. They engaged in competitions to see who could train and fly the most successful birds. It was impossible to keep the birds over India’s hot summers, and so the birds were turned loose, and new batches trapped in the fall. “We’d get a bird and keep it for years, but they had to get new birds and train them every year,” Craighead says.

The extended trip to India led to one of the several books John and Frank would author or co-author over the years: Life with an Indian Prince.

| |

|

|

To

learn how you can help the John J. Craighead Chair in Wildlife Biology

become a reality, contact: |

||

| |

|

|

Bringing Science to the People

Over the years the titles would become more scholarly—John, for instance, published “A Definitive System for Analysis of Grizzly Bear Habitat and Other Wilderness Resources Utilizing LANDSAT Multispectral Imagery and Computer Technology” in 1982—but the Craigheads never left the layman behind. “The positive influence of the Craigheads on public understanding and appreciation of wildlife and wildlife research has been incalculable,” John Weaver of the Wildlife Conservation Society wrote in a profile of the brothers in 1996.

“Much more than most people, the Craigheads were able to bring their science to the people,” said Jack Hogg, director of the Craighead Wildlife-Wildlands Institute, in 100 Montanans, a book about the state’s most influential people of the twentieth century, published by the Missoulian in 2000. “They made sure that people knew what they were doing and how it was relevant to the management of our public lands.”

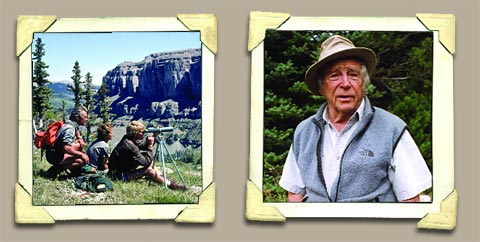

One of the Craigheads’ proudest accomplishments was the passage of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The brothers loaded their families in kayaks and canoes and tackled the mightiest rivers of the West. Their writings became much of the text of the act, and the documentary crews that followed them helped convince Americans of the need for the legislation.

“We had this director, he was slow at doing anything,” Craighead says. “He said he’d never really been outdoors before. He kept telling us, ‘You’ve got to give me time to get a feel for the river.’ So we put him in an Avon raft, looped line around the cleats on the raft, and told him to hold on tight. Then we took him over Salmon Falls [on the Salmon River in Idaho]. When the raft buckled, as it does, he went in. He got his feel for the river.”

It was a time, Craighead says, when the Army Corps of Engineers surveyed every river for dam sites. “They wanted to put dams everywhere,” he says. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act stopped that. Despite decades of research into dozens of subjects and their groundbreaking grizzly bear studies, Craighead makes no bones about it. “The best thing Frank and I did for conservation,” he says, “was the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.”

Frank died in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in 2001 at the age of eighty-five.

Life with Antonio

He stood somewhere between three and four feet tall. John Craighead, a small man himself, towered over the man. “He was all sinuses and scars, and about as alone as a man could be,” Craighead says.

He met Antonio on Palawan, one of the 7,000 islands that make up the Philippine archipelago. In the Navy and assigned to write a survival guide for naval aviators, Craighead traveled through South America and then into the Pacific doing research for the book.

“Admiral Tom Hamilton had promised me he’d get me out in the Pacific after we’d written this book,” Craighead says. “I was all ready to take off when the war ended. He told me he’d like me to go anyway and wrote out the orders. He wanted information on those who survived in that type of wilderness.”

And so Craighead headed for Palawan, which he says was something of an “open prison.” Antonio, he says, had been dumped on the island for killing a man who had stolen his wife. “All he had was a bow and three arrows,” Craighead says. “He’d kill monkeys and wild pigs to eat.”

Using a Filipino translator, Craighead quizzed Antonio to uncover information on survival in the South Seas, struggling with parts of it. “Monkey for lunch?” he says. “It was like eating one of your own kids.” Antonio chased wild pigs and monkeys through the jungle and Craighead chased Antonio. “I had a jungle hammock I put up over an old stream bed,” Craighead says. “Antonio slept by the fire. If you’ve ever watched a dog sleep, where his feet move back and forth, well, that’s what Antonio did. He was always running, even in his sleep.”

When an American base on Palawan shut down with the end of the war, Craighead loaded a Jeep with K rations and took them to Antonio. “They were getting rid of everything,” he recalls. “They had all these down sleeping bags, which were useless in the South Pacific anyway, a pile as big as a house they poured gasoline on and burned to get rid of. They were getting rid of the K rations too, so I took a load to Antonio. He opened them up, and he didn’t eat the food, but he ate the cigarettes. I left him with enough K rations to feed a lot of people. But I don’t know what he did with them.”

Craighead made sketches of Antonio in the jungle and wrote poems about him.

John Craighead has studied humans, too.

A Family Affair

John and Frank are far from the only Craigheads who have contributed to conservation. Their sister, Jean Craighead George, has written more than 100 children’s books about nature, including My Side of the Mountain, which was made into a movie.

She and her twin brothers each had three children apiece and virtually all of them carry on the family’s association with nature in one form or another. Craighead children are involved in the research of everything from polar bears to freshwater mussels. John W., who studies the latter, is also helping his father with his archives.

But the Craigheads’ biggest accomplishment may have been the hundreds of students they inspired over the years. Chris Servheen, who oversees grizzly recovery for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, remembers watching the National Geographic television specials as a youth. “From that point on, I wanted to do what I do today,” he says. “I know so many people who have the same story I have. They got into conservation because of what the Craigheads did.”

Wrote one former student: “Sometimes as a student you get lucky with teachers. John and Frank have always been very busy men, but they also took time to talk, to teach, to share their vast knowledge with the whole group of students around them at that time. We camped, fished, photographed, and spent long, hard hours working together. They shared their vision—their dream of how wild rivers and wild lands could fit into the modern American landscape mosaic—while teaching us about the stars and flowers, to live lightly on the land, and how vulnerable megacarnivores, wilderness, and wild rivers are to man’s expanding sphere of influence.”

For the Birds

It’s just a minute or two from the bustle of Reserve Street and Highway 93, but it could be a hundred miles. At the end of a dead-end street in lower Miller Creek, John Craighead enjoys a view with no other houses in sight from the rear of the home he shares with wife Margaret.

He is eighty-eight now, and the years have robbed him of his hearing but little else. More than seventy years after he and Frank trained a hawk named Comet, John Craighead’s life is still, in large part, for the birds. A raven he nursed back to health, Rudy, hangs around the backyard and a golden eagle raised from birth that refused several attempts at returns to the wild lives in a large aviary on the property. A couple of exotic birds fly freely inside the house, occasionally landing on John’s head to check on what he’s up to in the kitchen. And the artwork on the walls is largely of raptors rather than grizzlies.

As Craighead spins his tales of adventure, from India to the South Seas, from Washington DC to Yellowstone, son John W. rigs up fishing tackle for his father. His parents are about to leave for Florida, where John loves to get up, head for the beach, and cast into the ocean for hours on end. The outdoors he spent a lifetime working to protect are now his to enjoy. His days as a researcher are over.

But if UM’s Foundation is successful in establishing the John J. Craighead Chair in Wildlife Biology, his research will go on.

Vince

Devlin is a reporter for the Missoulian and a

frequent contributor to the Montanan.

Vince

Devlin is a reporter for the Missoulian and a

frequent contributor to the Montanan.