Bookshelf

Jeannette Rankin: A Political Woman

Jeannette Rankin: A Political Woman

by James J. Lopach and Jean A. Luckowski

Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2005, 312 pages, $34.95

Lopach is a UM professor of political science and Luckowski is a UM professor of education.

Even at its best, history can reduce the lives of prominent people to single symbolic acts. Montana’s Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to the U.S. Congress in an era when women in most states could not yet vote, is remembered most of all for the votes she cast against American entry into two World Wars, first in 1917 and again in 1940. A member of Congress for a total of only four years, her sole dissenting voice in eras of national certainty gained her notoriety—and later adulation—for her seemingly unrelenting idealism, however much of that idealism may have been owed to her equally unrelenting stubbornness.

Using correspondence, personal interviews, and numerous contemporary accounts, Lopach and Luckowski allow Rankin to step out from the shadow of her statue in the U. S. Capitol. Rather than construct a chronological account of Rankin’s life, Lopach and Luckowski use the book’s nine chapters to draw out and examine recurring themes in Rankin’s life. Though the book scrutinizes Rankin’s personal relationships closely, the most revealing chapters detail her considerable political savvy and the advantage she gained from her commanding personal presence. We learn what empowered and limited Jeannette Rankin, and how much she owed, both financially and politically, to her brother, Montana lawyer and rancher Wellington Rankin. [Editor’s note: Others familiar with Rankin’s life have taken exception to the con-clusions the authors seem to reach regarding her personal life and Wellington’s political influence.]

After graduating from UM in 1902, Rankin’s interest in social justice and the feminism of the day drew her to the New York School of Philanthropy, where she first encountered the intellectual prowess and expansive worldview that would shape her political life. Her congressional votes against war owe as much to the ideals she absorbed from her East Coast contemporaries as they do to her personal determination and western individualism.

Rankin spent the majority of her long life—she died at nearly ninety-three—working with feminist and pacifist organizations to advance the concerns of women and children. Long admired for her idealism, she mixed a fair dose of pragmatism into her politics that perhaps can best be summed up in a frequent appeal she made for women’s suffrage: “Men want women in the home and they want them to make the home perfect, yet how can they make it so if they have no control of the influences of the home. It is beautiful and right that a mother should nurse her child through typhoid fever, but it is also beautiful and right that she should have a voice in regulating the milk supply from which the typhoid resulted.”

Montana Surround: Land, Water, Nature, and Place

Montana Surround: Land, Water, Nature, and Place

by Phil Condon, M.F.A. ’89, M.S. ’00

Boulder, CO: Johnson Books, 2004, 184 pages, $15.00

Condon is an assistant professor of environmental studies at UM.

Phil Condon’s third book, a collection of personal essays, carefully examines the natural world surrounding him and tries to make peace with the realization that while he lives immersed in nature, as a human being he will always live slightly estranged from it.

Condon recounts how he moved with his first wife to rural land in Missouri, built a home, drilled for water, and planted trees, believing he would remain there the rest of his life. Change inevitably came, and he headed west to an entirely different place where among different people he discovered what land, water, and place owe to the forbearance and perseverance of time.

In one essay he tells of being haunted by the long-ago deaths of five mountaineers on Mount Cleveland, Glacier National Park’s highest peak. “The more I roam Montana, the more I see that any landmark is a place in time as well as space….[t]he better I understand the native wisdom that places are inseparable from the stories they hold and stories are indivisible from the places that mark them.”

The core of these fourteen essays is found in an essay where the author ponders the toxic chemical deposits now found in Arctic snow and ice, deposits originating halfway around the world. These leavings of human dominion over the earth remind Condon of a familiar childhood toy. “Pick up the snow scene in its small round globe of glass. Shake it and smile,” he writes. “Watch the snow settle and the scene change. It’s fun to do the shaking. And it’s also fun to imagine being one of the figurines. The truth is that, to a greater or lesser degree, we’ve always been both the shaker and the shaken.”

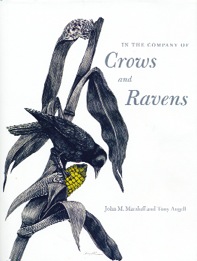

In the Company of Crows and Ravens

In the Company of Crows and Ravens

by John M. Marzluff ’80 and Tony Angell

Illustrated by Tony Angell

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005, 384 pages, $30.00

“If a person only knows three birds one of them will be a crow,” wrote Arthur Cleveland Bent, one of the leading chroniclers of bird lore in the twentieth century. There are forty-six species of crows and ravens in the genus Corvus and they are found throughout the world. Everywhere they live they are the stuff of legend.

In this book John Marzluff, a professor of wildlife science at the University of Washington, and Tony Angell, a writer and artist, bring together the best of crow and raven folklore, science, and anecdote. Beautifully illustrated with 100 original drawings, the reader is given an extended glimpse into an admirable and often maligned family of birds.

According to Marzluff and Angell, humans and the global clan of ravens and crows have been observing each other for millennia, beginning when crows learned that humans migrating across the landscape resulted in a fortuitous food supply. Until the time of the European plagues, crows and ravens were admired and protected for their scavenging ways. When they dutifully began cleaning up the multitude of corpses left by the plague, they and their descendants became hated harbingers of death.

In other cultures they have remained sacred beings, honored for their cleverness and reputed to help transport the souls of the dying across to eternity. Around the globe, the authors assert, crows and humans are partnered in a cultural co-evolution, each changing and enhancing the life and behavior of the other.

If our biggest gift to the crow and his brethren has been a steady food supply, theirs to us has included centuries of inspiration for art, literature, and legend. Cave dwellers scratched images of crows onto their walls. Early hunters and gatherers built totem poles in their honor. Hindus and Japanese sought wisdom from them, and Shakespeare wrote them into his plays.

One of the best known legends of ravens originates in seventeenth-century England, where, following the fire of 1666, six ravens were spared from persecution and allowed to live in the Tower of London. Warned by a royal astronomer that destruction of the ravens would mean an end to his reign, King Charles II arranged for a corps of “raven masters” to care for the birds. Not wishing to tempt fate, British rulers have kept ravens in the tower ever since.

Drift Smoke: Loss and Renewal in a Land of Fire

Drift Smoke: Loss and Renewal in a Land of Fire

by David J. Strohmaier, M.S. ’99

Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 2005, 177 pages, $24.95

A historian and wildland firefighter of fifteen years, David Strohmaier uses this book to meditate at length about the very real loss engendered by wildland fire—and the inevitable renewal that follows. An evocative thread runs through the book, drawn from the story of an 1845 wagon train that made its way across a parched section of Oregon’s high desert. As the train traveled through the cool of the night, scouts rode ahead to mark the proper route with fiery “cairns” of burning sage and juniper. Similar cairns, traditionally built of rocks, still mark trails in isolated areas of the West today.

Strohmaier uses four cairns of loss—fire, life, livelihood, and place—to guide the reader through his recollections and conclusions about the role of wildfire in the contemporary American West. He explores how native peoples traditionally used fire to improve grazing land or nurture the growth of particular food sources. He writes how fire, whether caused by humans or by lightning, “frees the nutrients in aging hulks of trees and brush and rank mats of grass.”

The necessity of fire in the landscape does not, in Strohmaier’s view, lessen the tragedy and loss felt when human life, livelihood, or beloved places disappear in its wake. While stopped at the second cairn, the loss of life, Strohmaier discusses two of the most recognized instances of death at the hands of wildland fire: Montana’s Mann Gulch tragedy in August 1949 and the deaths of fourteen firefighters on the slopes of Storm King Mountain in Colorado in 1994. He contends that recognizing and honoring these losses is essential to the process of grief and ultimate renewal.

BookBriefs

Paddling the Yukon River and its Tributaries

Paddling the Yukon River and its Tributaries

by Dan Maclean ’95

Anchorage, AK: Dan Maclean, 2005, 192 pp., $19.95

More than 4,000 miles of river travel are covered in this guide, with each river charted from beginning to end, including access points, re-supply options, navigation tips, and a range of trip lengths. Includes thirty-five original maps.

Mimicking Nature’s Fire: Restoring Fire-Prone Forests in the West

Mimicking Nature’s Fire: Restoring Fire-Prone Forests in the West

by Stephen F. Arno, M.S. ’60, Ph.D. ’70 and Carl E. Fiedler, M.S. ’70

Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005, 242 pp., $44.95, $24.95 paperback

Fiedler is a UM research professor.

Drawing from their own experience and examples from varied forest types in western North America, the authors offer practical techniques for designing and implementing a range of forest restoration actions.

The Laugh of the Water Nymph

The Laugh of the Water Nymph

By Doug Ammons ’83, M.A. ’89, Ph.D. ’90

Missoula: Water Nymph Press, 2004, 239 pp., $29.50

An engaging meditation on extreme kayaking and how outdoor pursuits can be a metaphor for a life well led.

The Sleep Accusations

The Sleep Accusations

by Randall Watson, M.F.A. ’86

Spokane, WA: Eastern Washington University Press, 2005, 69 pp., $15.95

Winner of the 2004 Blue Lynx Prize for Poetry, this collection is rich with imagery and a lean toughness.

Jerry’s Riot: The True Story of Montana’s 1959 Prison Disturbance

Jerry’s Riot: The True Story of Montana’s 1959 Prison Disturbance

by Kevin S. Giles ’74

Stillwater, MN: Sky Blue Waters Press, 2005, 445 pp., $19.95

The story of the conflict between convict Jerry Myles and Warden Floyd Powell that led to a riot in Montana State Prison and made national news over three days in 1959.

American Catholics and the Mexican Revolution 1924-1936

American Catholics and the Mexican Revolution 1924-1936

by Matthew A. Redinger ’86, M.A. ’88

Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005, 272 pp., $22.00

Redinger, a professor of history at Montana State University-Billings, explores the response of American Roman Catholics to the social reforms instituted by the Mexican Constitution of 1917, which included nationalizing church property and closing religious schools.