The Cutting Edge

World-class Heart Institute Celebrates 12 years Story by Ginny MerriamPhotos By Michael Gallacher

Missoula heart surgeon Matt Maxwell likes to tell a story about his work. It starts like this: “When I first met Barry Flamm, he was dead.”

Flamm, a visiting professor at UM in the winter of 2002, had collapsed while seeing a student in his office. He was taken to the St. Patrick Hospital emergency room with a ruptured aorta. Maxwell was one of the cardiac surgeons who fixed him up. Recently Maxwell received a postcard from Flamm, an internationally known natural resource consultant. Flamm was working as a volunteer in the Philippines, helping build sewers where they were badly needed.

“This is really why we do what we do,” Maxwell says. “I tell people, ‘Send me a postcard. Show me you’re using it.’”

Maxwell might not be in Missoula if it weren’t for Carlos Duran. And Duran, a Spanish-born, internationally praised cardiac surgeon, valve surgery pioneer, and Renaissance man, tells his own story about how he landed in Montana to build and nurture the International Heart Institute of Montana.

In 1995, Duran had just finished seven years as chair of the Cardiovascular Department at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He had become friends with fellow cardiac surgeon Jim Oury, who had moved to Missoula and had interests similar to Duran’s in the use of natural tissues in heart valve surgery. Duran traveled to New York City for the annual meetings of the American Association of Thoracic Surgeons, and expected to see Oury there. But when Oury invited him to come up to a hospitality room at the convention, he didn’t expect to see the president of The University of Montana, the president of St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center and one of Missoula’s most respected cardiologists.

“Lo and behold, I opened the door, and there was George Dennison, Larry White, Stan Wilson, and Jim, saying, ‘Would you come here?’” Duran remembers today. “They had me against the wall.”

What they wanted to build was what Duran, in retrospect, had been working toward his whole career: a place where the patient’s bedside met the scientist’s bench—an institute that brought together cardiac surgeons and cardiologists, who take care of patients, with the scientists on the front edge of cardiac research.

They had the ingredients for a recipe that Duran had known for years would make the superlative situation. First, a smaller but committed hospital where everybody knew everybody else. Second, no medical school, so no medical school politics. Third, a vibrant city small enough to be livable and big enough to bring in and accommodate heart specialists from around the world for workshops and seminars. And, the crucial piece, a university with a commitment to science and collaboration.

President Dennison smiles today at their method for recruiting Duran. He, White, Oury, and Dave Forbes, dean of UM’s College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences, had brainstormed considerably before making the approach.

“We talked about the possibility of an institute,” Dennison recalls. “In order to make it go, it was clear we had to have someone with real stature in the cardiovascular sciences.

“He was going to be present at the thoracic surgeons’ meetings, so we thought we’d gang up on him.”

That night, they talked and talked, he remembers. They ate dinner at Sardi’s and talked some more.

“They were very keen on it, both George and Larry,” Duran says today. “So it was, ‘Goodbye, Saudi.’ I was lucky to be in the right time and place.”

Hearty Success

Today, as the Heart Institute marks its twelfth birthday, its accomplishments tell the story. Five cardiothoracic surgeons in Missoula and Kalispell perform more than 400 open-heart surgery procedures each year. The Institute’s Cath Lab is now three busy labs, where four on-site cardiologists perform 2,500 interventions each year. They’re in affiliated practice with three more cardiologists in rural areas, two at Western Montana Clinic, and five through the CardioPulmonary Associates of Montana in Missoula. The International Heart Institute is known throughout the world for its expertise in heart-valve surgery.

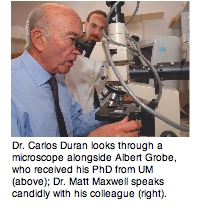

The Institute’s umbrella organization, the International Heart Institute of Montana Foundation, also includes research that takes place in UM’s College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences. One of its scientists recently held more National Institutes of Health research dollars than any other scientist in the state. The work takes place at the experimental bench and also in a University surgical suite—complete with imaging devices—where researchers learn from procedures on sheep and rabbits.

“For many years, UM has been looked down on as not having research, being a small liberal arts university,” says Dave Forbes, who wears two hats as dean of the college and as a St. Patrick Hospital board member for nine years.

That’s not true any more, he says. The Skaggs School of Pharmacy now ranks fifth in the nation in grant money per faculty member. And it’s seventh in the nation for total NIH grant money.

“It starts with Carlos’ vision, which permeates not only our Heart Institute but our Montana Neuroscience Institute and our Montana Cancer Center,” says Vernon Grund, chair of UM’s Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “What it does is it gets our scientists into the hospital, and it gets the physicians into UM.”

The Foundation’s Vascular Biology and Tissue Engineering Labs mean active research goes on in the hospital itself.

Every summer, more than 100 cardiac specialists travel to Missoula for the Rocky Mountain Valve Symposium and the Echo Montana conference. The Valve Symposium, affectionately called “Rocky” by the specialists who have attended from thirty-five states and forty countries since its inception in 1989, looks at the latest problems and solutions in valve disease and repair. The distinguished faculty and visitors often include Sir Magdi Yacoub of London, who pioneered the heart-lung transplant, and British cardiac surgery pioneer Donald Ross, inventor of the complex Ross Procedure surgery used for failing aortic valves, which he built on Duran’s work. The symposium is hands-on: Heart Institute and visiting surgeons work on cases in St. Pat’s operating rooms, televised to the hospital conference center. Technology enables a lively discussion between the operating room and the auditorium.

Five times a year, smaller groups of specialists come to Missoula for workshops, where they share knowledge in three intense days led by Duran.

“Dr. Duran is an icon,” Forbes says. “He’s internationally known.”

As president and CEO of the International Heart Institute of Montana Foundation and chair of Cardiovascular Sciences at UM, Duran presides over it all. Degreed as an MD and a PhD, he is known for his invention of the Duran Ring for mitral-valve reconstruction. His work has led to 450 professional papers presented at scientific meetings, thirty-three chapters in medical textbooks, and more than 300 peer-reviewed publications.

“[Duran has] always been a champion of learning,” says Jim Foster, who retired as an executive after thirty years with Medtronic Inc., the world’s leading medical technology company and manufacturer of the Duran Ring. “You’re always learning. Never think you know everything. There’s always something that’s going to surprise you. He’s always been unique in a world filled with lots of egos.”

In short, says Foster from his Minneapolis home, “He’s the real deal.”

Duran deflects praise. He’s just the convener, he says.

“I’m a good surgeon. That’s all.”

Collaboration and Connection

Among the first things Duran tells visiting specialists is that he wants them to question him.

“Repeat after me: I do not believe a word you say,” he tells them. “Listen, but look into it. If I get a guy who repeats what I say, what am I learning? Why can’t he have an idea better than mine? I just want to be in the right place so I can pinch your idea. Otherwise, it’s boring.

“No one possesses the truth. I can’t stand the person who possesses the truth.”

The challenge, the intellectual jousting and sparring produce a whole that’s greater than the sum of the pieces, he says.

“Creation is a fascinating topic,” he says. “How does that happen?”

Some of Duran’s best ideas have ripened over informal coffee. Once, he met an expert in ocean waves at a pub whose work illuminated a problem in the aortic valve. Duran was so excited he took the man back to the hospital lab to apply their thinking late into the night.

“It was so fruitful—new vistas in something I’d been looking at for years,” he says. “There’s great intellectual pleasure in that sort of clicking.”

One of the models for Duran are the twice-weekly case meetings of the cardiac surgeons at the Heart Institute. Every Monday at 7 a.m., they meet to discuss the week’s cases. In this case, should you operate? Is there something else to think of? On Friday morning at seven, they meet again. What happened here? What did you learn? Sometimes the passionately defended position of Monday morning has melted into another view altogether.

“Little by little, the indications become homogenized,” Duran says. “It’s the mind of everybody. Not just one guy. It’s much better for the patient.”

The research benefits too. It is translational, meaning it goes from the science bench to the patient’s bed. In other places, that can take years. But in Missoula, the bench is very close to the bed—just across the Clark Fork River that winds through Missoula, past campus, and the hospital.

“If the scientist is a long way from the bed, it’s much more difficult,” Duran says. “You don’t meet, you don’t talk.”

Duran began to see the need for collaboration in the cardiac world in his first job. After he spent fourteen years in post-graduate training in Paris, Madrid, and at Oxford University in England, the University of Navarra in Pamplona, Spain, hired him to start a cardiac surgery program in 1967.

“I had to organize the place and direct the colleagues and learn the politics of a university hospital,” he says. “Part of it was learning to get people together to work toward a common goal. That’s the main challenge—getting to work together with differences in training, differences in intelligence, and differences in temperament.”

In 1974, Duran went to a similar challenge at a 2,000-bed hospital at the University of Cantabria in Santander, Spain. There, he started a heart transplant program and continued learning to get cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to work with each other while an active research program also demanded his attention.

After General Francisco Franco died in 1975, hospitals came under the rule of the Communist Party. That eventually sent Duran looking for a new place to work.

“I didn’t like the system with the communists,” he says. “I disagreed with the way they were going.”

By then he had the idea of an institute that brought together cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and scientists interested in the heart.

“You put them all together, it’s very, very rich,” he says. “The link is not your specialty, your training. The link is what you’re interested in, what you’re good at.”

In 1988, the Saudis lured Duran to King Faisal’s 650-bed hospital in Riyadh with the request that had become the theme of his career: make a single department out of disparate groups of surgeons, cardiologists, intensivists, and other heart specialists. Money was no object. The system was authoritarian, so the things Duran needed were simply ordered up. He and his wife, Begonia Gometza, also a physician, lived in a villa on the hospital grounds. They devoted themselves to work. It was, Duran says, “Fantastic.”

But the work of creating collaboration has never been easy, he says.

“Physicians have been trained all over the world to make decisions on their own, to be independent,” he says. “Initially, there is reluctance from the guy who has been all his life on his own. And there’s a suspicion: What is this guy going to do? How much is he going to interfere with my work? To get them all together requires a certain amount of humility.”

Among Duran’s long associations is his relationship with Medtronic. In the 1970s, when Duran began using the Duran Ring to repair mitral valves, nurses made the ring to order in the operating room. It worked, but it took time in a stressful situation. Duran’s friend Warren Hancock of Hancock Laboratories picked it up and started manufacturing it. Medtronic, founded by electrical engineer Earl Bakken, who invented the first wearable, transistorized pacemaker, wound up with the product through acquisitions. Still the manufacturer of the Duran Ring, Medtronic helps fund visits by cardiac specialists to Missoula.

Duran’s collaborative model works for industry too, Foster says.

“We can be a center of excellence by integrating across the boundaries,” he says, “by involving ourselves with research and with clinicians.”

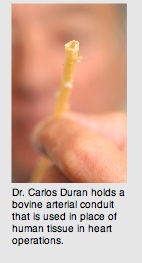

One of the Heart Institute’s ongoing projects recently brought in a $1.7 million federal grant. The money will fund testing of a sterile, freeze-dried replacement conduit developed in Heart Institute laboratories and patented. The invention is revolutionary for use in difficult trauma settings, such as combat, where an injured patient’s survival and the recovery of arms and legs depend on restoring blood flow after vital blood vessels are damaged. The tissue-engineered replacement conduits will be easy to transport, store, and rehydrate. They will be made in a variety of sizes and strengths. Tests with animals show that the patient’s own cells accept and grow around the grafts.

Continuing Duran’s Legacy

Today the Heart Institute and its Foundation face a new challenge: Duran’s retirement. While he doesn’t expect to leave all involvement with the Institute and his work, he will turn seventy-five on his next birthday, and he’d like time for other things. It’s time-consuming being a professor and chair of Cardiovascular Sciences at UM, medical director of the Heart Institute and a surgeon there, and president and CEO of the International Heart Institute of Montana Foundation.

Duran and his wife have seven children who live around the world, and they’d like to visit them. They are devoted sailors, and Duran wants to sail a trawler up the Inside Passage to Alaska. He wants to take time over a Saturday-morning bagel and prosciutto, watch football, and marvel at the mountains while he fills his car with gas. The decision is made, he says. “I feel much more relaxed. I’ve been telling the young people, ‘Hey, man, I’m not eternal.’”

UM’s $100 million Invest in Discovery campaign includes $2.5 million for an endowed chair in cardiovascular sciences to perpetuate Duran’s legacy. The Heart Institute Foundation is intimately involved in the fundraising and the search, along with a committee of distinguished local residents.

At the same time, the collaborators are working to recruit a new senior scientist.

“We’re in the middle of a very vigorous crusade,” Grund says.

The person who sits in the endowed chair must be a convener, above all.

But he or she will have to be thought of in a different way, says Maxwell.

“We have to say, ‘Look, we’ll never have another Carlos. We will never,’” he says. “All the elements to be something very special are still here. We are going to have to do this in a different way. It’s going to have to be even more collaborative, less personality-based.”

“It needs to be a person who is able to interact well with both clinicians and scientists,” says Forbes. “We’ll need somebody who is able to operate on both sides of the river. Change is with us.”

Duran, President Dennison says, won’t be distant.

“I’m hoping he’ll continue to provide advice and help with the course,” Dennison says. “I’m pretty much committed to making sure that happens.”

![]() Ginny Merriam ’86 is a freelance journalist who lives in Missoula. An award-winning reporter for the Missoulian for 20 years, she currently is the communications director for the City of Missoula.

Ginny Merriam ’86 is a freelance journalist who lives in Missoula. An award-winning reporter for the Missoulian for 20 years, she currently is the communications director for the City of Missoula.