In a New York Minute

Broadcast Alum Shines In National News Anchor Spot By PATIA STEPHENS

5:18 a.m.

It’s snowing lightly in midtown Manhattan as a black town car drops CBS news anchor Meg Oliver off at her apartment building. Perfectly coiffed and made up after a long night at work–and on television screens around the world–she will ride the elevator up to her apartment, scrub her face clean, feed her five-month-old daughter, then go to bed.

A 1993 graduate of The University of Montana School of Journalism, Oliver became a news anchor on the overnight news program Up To The Minute in March 2006. With more than 800,000 U.S. viewers—many of them insomniacs or parents of newborns—Up To The Minute is broadcast on CBS affiliates nationwide. On the East Coast, it airs from 2 to 6 a.m.; in Missoula, it runs from 1 to 5 a.m. Up To The Minute also provides American news around the globe via cable television. It’s on, for example, at 10 a.m. in Iraq.

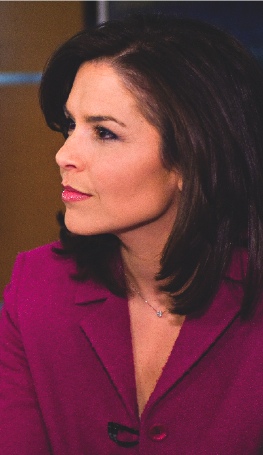

Oliver’s training and experience have prepared her for the national anchor position, and her good looks and warm, intelligent demeanor have made her a natural.

Waking at 1 p.m., Oliver begins her workday well before she heads to the CBS studio each Sunday through Thursday evening. While caring for her daughter, Maria, she checks phone and e-mail messages, converses with her boss, monitors the Associated Press wire service, reads, researches, and mentally prepares for the interviews she’ll conduct that night. By the time she blazes out the door of her apartment building at 8 p.m.—stopping for a frappucino at the corner market during her brief walk to work—she’s raring to go.

When I was assigned to write this story, the name Meg Oliver rang a bell or two. Googling her, the first thing that turned up in my desktop results was an e-mail she’d sent me two years earlier, complimenting me on the TGIF newsletter I edit for the University. Later, I realized I remembered her face from the Flathead Valley, where I worked at the Whitefish Pilot newspaper and she was an anchor at KCFW-TV in her first job out of college.

Small world.

8:25 p.m.

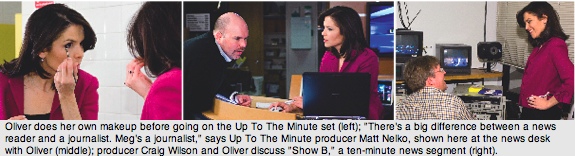

In a rather ordinary ladies’ bathroom in CBS News headquarters on West 57th Street, Oliver hangs her coat on a hook and, reaching into her purse, places an array of cosmetics and implements on a narrow shelf below a large mirror. The mirror is theatrically ringed with small light bulbs, several of which are burnt out. Oliver runs a microphone and cord under her blouse and jacket, changes from street shoes into heels, then speedily applies makeup and fixes her hair.

Five minutes later, she breezes into the Up To The Minute studio, greets her colleagues, logs into her computer, then picks up the phone to call downstairs and let them know she’s on the job and ready to take over if breaking news happens.

In the middle of the room is the brightly lit set where Up To The Minute is taped. The set comprises a news desk on a round elevated platform, a background partition of frosted glass, graphic backdrops on the walls to either side, and, in front of the desk, a half-circle of monstrous black cameras. The television cameras are operated via robotics from the nearby control room. Cables and cords run everywhere.

Buzzing with the quiet activity of a dozen people, the studio smells like Chinese food. It could use a good decorator.

8:45 p.m.

Oliver and her boss, Executive Producer Bob Bicknell, discuss strategies for interviewing the night’s main guest, three-time presidential candidate Ralph Nader. Nader’s here to promote his new book, The Seventeen Traditions, and a documentary film about his life, An Unreasonable Man.

Oliver says to Bicknell, “I thought I’d start by asking him what people really want to know: Is he running in 2008?”

“Hit him,” Bicknell agrees affably. “Hit him!”

Despite Nader’s new book getting delayed in the “anthrax room” where all CBS mail must pass, working a second shift on the CBS Morning News, and a fussy baby who didn’t want to nap, Oliver managed to read Nader’s book in barely one day. “I really enjoyed it,” she says. “It was interesting.”

Born and raised near Detroit, Michigan, Oliver was inspired by her maternal grandmother to pursue a broadcasting career.

“My grandmother’s goal was to have one of her grandkids read the six o’clock news on the air,” says Oliver, who has two older brothers and fifty-five first cousins. “I knew I wanted to be a TV reporter in grade school.”

In high school, when she began looking for journalism schools, Oliver came across The University of Montana.

“It had this phenomenal journalism program,” she says. “I looked at other programs, but they taught theory and didn’t offer the hands-on approach that UM has.”

She and her mother flew out for a visit during Orientation. Back then in 1989, “Nobody knew where Montana was,” she says. “It took so long to get there. When we landed, it was this gray, cloudy day, and we couldn’t see anything. The airport had three gates, and deer heads, and that stuffed bear. I said to my mom, ‘I’m not going to school here.’”

But the next day, touring campus and meeting people, including a journalism student Advocate who took Oliver under her wing, Oliver changed her mind. She never regretted it.

“Going to UM was definitely one of the best decisions I’ve ever made,” she says. “Right from the get-go, I loved it.”

9:15 p.m.

Four men in dark business suits arrive in the studio—Nader and his assistants. Nader, tall and tan, shakes hands with Oliver and Bicknell, then follows her onto the set. They chat while Nader gets miked up and Oliver powders her face. Then the cameras roll, and she hits him: Is he running? “It’s too early to say,” Nader calmly responds.

Eight minutes and thirty-five seconds later, the interview is over. It will air as is, without editing, during the hour-long Up To The Minute newscast, which repeats throughout the night unless there’s major breaking news. Later, I ask Oliver if it’s scary to ask the tough questions. She cocks her head and replies, “No. It’s fun.”

Oliver admits she was nervous when she first arrived at UM as an out-of-state freshman, but she soon found her place. “Majoring in journalism and pledging Delta Gamma were the two best things I did,” she says. “They gave me a community.”

She also found a mentor in broadcast journalism Professor Emeritus Bill Knowles. “Bill captured my attention right away in Journalism 101. He is still my mentor to this day. He gave me confidence.”

Oliver and Knowles separately tell me about an incident they remember. After she and a fellow student had gone to tape a story on location for the Student Documentary Unit, Knowles called her into his office.

When she heard, “Oliver, get in here,” she thought she was in trouble. “He yelled at me for letting [the photographer] shoot me too wide. He went on and on about quality control. He said, ‘You’re going to be a reporter. Don’t let them shoot you that far away.’”

Knowles tells it slightly differently. He says he told the male photographer: “When you have a reporter who looks like Meg does, you shoot her tight.”

Either way, it was a pivotal moment for Oliver. “I left his office thinking, ‘Wow, he really thinks I’m going to be a reporter,’” she says. “That was the moment I knew it was going to happen.”

150 Percent From partyer to producer, NBC executive found her passion at UM

From partyer to producer, NBC executive found her passion at UM

Terry Meyers ’91 is the classic high-powered female executive. As a top producer at New York’s WNBC-TV, the largest television newsroom in the country, Meyers averages eleven-hour work days and is on call 24/7. Although after ten years as an executive producer she now tries to take vacations, she still loses a week and a half of paid leave every year. On the sixth floor of Rockefeller Center, Meyers is executive producer of two news programs—an hour at 5 p.m. and a half hour at 6 p.m. She’s also responsible for getting breaking news on the air. Her job involves making one tough decision after another—what news to cover, which reporters and crews to send, in what order stories will run, and how much time they’ll get. She decides everything from when to break in to regular programming to whether to send the chopper. “I do a lot of running in circles. I basically delegate,” Meyers says modestly, while her managing editor walks by and counters, “She’s the best producer in the business.” Meyers recently spearheaded the move to digital and high-definition TV at WNBC, which serves some twenty million people in the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. “If I make mistakes millions of people see it,” she says. “I have to know everything that’s going on. And I have to know details." Coming from WCBS, Meyers had been on the job at WNBC a month before September 11, 2001. “We heard a plane had hit the World Trade Center, and that there was a fire,” she says. “I turned and looked at a bank of monitors trained on the Trade Center. I said, ‘That’s not just a fire. There’s a hole in that building.’” They were live on the air when the first tower came down. “At one point we thought this building was a target,” she says. “We’d heard six planes were in the air. The general manager said, ‘You’re all here voluntarily from this point out.’ People were crying, leaving. It was chaotic.” Meyers decided to stay. With phones down, she e-mailed her parents to tell them she was staying, and that she loved them. WNBC’s transmitter—and a technician—had been on the roof of one of the towers, so only those with cable or rabbit-ear antennas could pick up the station's signal. “We have an obligation to the people of the tri-state area,” she says. “That’s why I do it.” With no subways and Manhattan covered in ash, she walked home at 2 a.m. down the middle of 50th Street. Meyers likes to say she gives 150 percent no matter what she does. “That would be true whether I worked here or at Burger King,” she says. “If I worked at Burger King, I’d be selling the most burgers.” It was also true when she was a student at UM. A Virginia native who had moved to Spokane, Washington, with her family, Meyers came to UM wanting to be a photojournalist, but was more interested in going out than studying. “I was a huge partyer my first two years,” she says. “I wasn’t really interested in learning.” Then she took a writing class from broadcast journalism Professor Joe Durso. “He assigned us a story about milk prices,” she says. “So I wrote a story that opened with the line, ‘If you drink a lot of milk, you’re about to pay a lot more.’ He praised me for that, and I thought, ‘Maybe I’m good at this.’” She says Durso and Bill Knowles pushed her to write and kindled her interest in storytelling. “They really took an interest and really cared,” she says. “Especially Bill Knowles. He took care of me, guided me.” Of Meyers, Knowles says, “She’s one hell of a talent.” In retrospect, Meyers is grateful for UM’s hands-on approach, like having to shoot and edit her own video. “I used to think, ‘Why am I doing this?’ Now I thank God I had to do that. It put me way ahead of the curve.” On the job at WNBC, Meyers believes she’s respected for her journalism skills and ethics, things that were stressed in every class she took at UM. “I think the education I got at The University of Montana is comparable to any of the major journalism schools. I got the best education I could have gotten anywhere.” |

10:15 p.m.

Oliver’s next interview is with CBS News foreign affairs analyst Pam Falk, a lawyer and professor who radiates an intense intelligence. While Oliver and Falk perform last-minute hair checks on the set, Oliver’s boss is in the control room at the producer’s mixing board, where a red Staples “Easy” button lies. But as the door slides shut, it soon becomes apparent that what Bicknell and his two directors, James McGrath and Chris Easley, do in here is anything but easy. Like the cockpit of a fighter jet, the control room is lit up with a million switches and lights and a dozen incoming and outgoing broadcast feeds on tiny wall monitors. Bent over a microphone, Bicknell speaks into Oliver’s earpiece.

“Meg, you ready?” he says. “This is six minutes. And it’s a ‘Welcome back.’”

He counts down the time, then Oliver smiles and speaks into the camera: “Welcome back. It’s forty past the hour.” She turns to Falk. “Good morning, Pam.”

The women discuss the latest deadly events in Iraq and a potential build-up to war with Iran. In the control room, it’s barely controlled chaos as the three guys toggle switches and shout out commands, and a jukebox-type machine called a beta cart noisily switches tapes. But it’s over almost as soon as it begins. The cameras stop rolling, the control-room adrenaline subsides, and the door opens. Bicknell asks me, “What do you think?” I respond: “Crazy!”

Oliver wanders in rubbing her nose. “I had to sneeze for about a minute and a half,” she says.

Behind her, Falk sticks her head in the control room door. Before taping, she had jokingly told me she was president of the Meg Oliver International Fan Club. Now she says, “I want to give you a serious quote. I’ve never been with an anchor who’s as informed as Meg is. She’s a dedicated anchor. She’s also smart, beautiful, vibrant …. She’s wonderful.”

11:30 p.m.

Oliver leaves the studio to fill a bottle—despite her busy schedule, she’s still breast-feeding Maria—and retouch her makeup and hair. “By the time I go home, I’ve done my makeup three times,” she says. “Then I go home and feed my five-month-old daughter. It’s not very glamorous.” She laughs.

Juggling a baby and a high-pressure career hasn’t been easy, but she’s pulling it off with the help of her husband, John, and her mother, who came from North Carolina to help take care of Maria until Oliver finds a nanny.

She and John, a Harvard-educated corporate lawyer, married in 2002 after meeting through a Montana connection. Oliver, then working as a reporter and anchor in Detroit, had gone to Texas to attend her friend Amy’s wedding. The two young women had been co-workers in Kalispell, as well as roommates, renting a log cabin on Flathead Lake.

Amy’s groom and John also had been roommates. “We totally hit it off at the reception,” Oliver says. “Our first date was five days long. On our third date, we went to Greece. We just knew.”

Oliver says a supportive husband, good help, organization, and yoga help her stay on track. “I’m just learning to strike the balance between work and family,” she says. “You can’t really have it all, but you can have a little bit of it.”

Oliver says she always knew she wanted to go back east, because her family is there. “But I cherish my memories of Montana. I loved, loved, loved Montana. My heart is there.”

Midnight

While the staff breaks for ice cream bars, Oliver is back on the set preparing to tape pre-production lead-ins for packages that have come in from reporters. High heels kicked off under the desk, she runs a teleprompter with her foot, reading over the script that scrolls down its screen. If the teleprompter were to crash during live taping, she’d revert to the paper scripts she holds on the desk.

At 12:30 a.m., pre-production taping begins. Here she has the luxury of backing up, like when she flubs the word “cafeterias” in a school lunch food-poisoning story. But most of the time, she’s flawlessly articulate.

In between tapings, still seated at the anchor desk, Oliver chats with people off-camera. At 12:38 a.m., she stifles a yawn. At 1:09 a.m., she tapes a “Moneywatch” segment. At 1:11 a.m., she reads weather. Pre-production taping is done by 1:30 a.m., and Oliver and her crew take time to relax and B.S. a bit before they go live at 2 a.m.

It’s clear from the joking and teasing that the twelve-person Up To The Minute team enjoys working together. It’s also clear the staff has genuine affection and respect for Oliver. In the television news industry, they tell me, the behind-the-scenes producers, directors, and technicians tend to stick around for years, while the “talent”—anchors and reporters—come and go. Some make a better impression than others.

“There’s a big difference between a news reader and a journalist,” says producer Matt Nelko. “Meg’s a journalist. She’s great. She really is.”

“It’s a pleasure to work with her,” agrees her boss. Bicknell, who’s been at Up To The Minute for seven years, hired Oliver after seeing her resume tape.

“It had that X-factor,” he says. “You know it when you see it. You could tell she had the ability and the brains.”

Her UM mentor agrees. “She was one of those you see the talent in,” Knowles says. “She was really into good reporting and good writing.

“I remember sitting around a table at a restaurant in Helena, and [the late UM broadcast journalism professor] Joe Durso said how impressed he was with Meg. I said, ‘She’s a winner. She’s going to make it.’”

2 a.m.

In the control room, Joe Gelosi is at the producer’s desk for “Show A,” ten minutes of live news at the top of the hour. Gelosi, whose Italian good looks remind me of Al Pacino, has spent the evening writing and editing stories for this news block. The control-room adrenaline is amped up higher than before, because this is live, not taped. There’s no room for errors, no way to back up and start again.

When taping begins, the men do their thing at the mixing boards with fighter-pilot precision, shouting commands, eyes on the clock, always on the clock. Gelosi speaks succinctly into Oliver’s ear, telling her to speed up or slow down as needed. On the monitors, she’s moving seamlessly between news stories about Senate hearings on the Iraq War, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Code Pink protests. When the live segment finishes and the newscast goes to commercial, Gelosi spontaneously erupts.

“Beautiful,” he says. “Beautiful! She’s SO good. She does it every time.”

“It,” he explains is all about timing. Getting a live news broadcast to fit precisely into its allotted time slot—neither a few seconds too long nor a few seconds too short—is an art form. Oliver’s a pro, he says.

“It’s easy with her because she’s great,” he says. “Not only is she good, she’s nice. She doesn’t have the ego that a lot of talent has. We’re just lucky. We’re really lucky.”

Knowles agrees with the lack of ego assessment. “What sets Meg apart is that she’s not full of herself,” he says. “She understands that you have to be a good person to make it in the business.”

Oliver, for her part, is grateful for Knowles’ advice to “never, ever burn a bridge in this business. He said, ‘It will come back to haunt you, because everyone knows everyone.’ I had one boss who was awful, and Bill’s advice kept coming back in my head. I took it to heart, and thank goodness.”

She also credits Durso and UM faculty members Ray Ekness and Gus Chambers for her success. “In college, [professors] help you find a game plan.

“I graduated with a resume tape in my hand,” she says. “How many students do you know who shoot packages that run on local news?”

2:26 a.m.

Producer Craig Wilson takes over in the control room. I can’t shake the feeling that he looks just like UM journalism Professor Dennis Swibold, except on speed.

Wilson’s “Show B,” also a 10-minute news segment, runs at the bottom of the hour. He’s leading with a breaking wire story about alleged waste of taxpayer funds in Iraq. “I’m going to have to kill something,” he says. Fortunately, “kill” is a figurative term here—he’s looking at his computer for a story to cut. “‘Minimum’ is out,” he tells Oliver over the microphone.

Without video or time to look over the script, she goes live with the new lead story.

“When there’s breaking news, she gets nothing,” says Wilson, who’s worked at Up To The Minute for thirteen years. “She’s left there hanging. There’s no hand-holding, no spoon-feeding.

“It all rests on her,” he says. “I call the plays, but she executes them.”

When the broadcast is over, he shoots his fists into the air. “Great job, Meg.”

Oliver, who interned in New York at Good Morning America, came to Up To The Minute after thirteen years as a reporter and anchor at TV stations across the country—from her first part-time job at KECI-TV in Missoula to KCFW in Kalispell, Northwest Cable News in Boise and Seattle, WTIC-TV in Hartford, Conn., WWJ/WKBD-TV in Detroit, and KGPE-TV in Fresno, Calif., where she was the 5, 6, and 11 p.m. weekday anchor. When she was named Up To The Minute anchor, she had been serving as a freelance correspondent for CBS Newspath in Washington, D.C. There she covered major news stories, including the nomination of Chief Justice John Roberts and President George Bush’s 2006 State of the Union address.

Oliver’s work has garnered numerous honors, including four Associated Press awards, two Society of Professional Journalists awards, and eight Emmy nominations.

|

Knowles It All

His business card says “William L. (Bill) Knowles, Professor Emeritus,” but with his home and work addresses, phone numbers, fax, and e-mail address listed on it, he hardly seems retired. Indeed, Bill Knowles taught his definitive Journalism 100 class, Introduction to Mass Media, last fall under a post-retirement contract. He insists it’s his final one, but some of us will only believe it when we see it. Knowles came to UM in 1986 after a twenty-two-year career as a television producer and executive at ABC News bureaus in Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and Atlanta. He co-founded the Student Documentary Unit at UM with his late colleague and friend Joe Durso. After twenty-one years of teaching and influencing the minds of generations of print and broadcast journalists, the beloved professor retired last year. He continues to maintain an extensive network of alumni and professional contacts through e-mail, phone calls, and visits. “I keep in touch with students who ask for it and who keep in touch with me,” he says. “I believe that a professor in our business should be available for post-graduate career counseling.” Alumna and CBS anchor Meg Oliver says she still calls Knowles when she needs a contact. “He is the king of networking,” she says. “I’ve never met someone so connected in this business.” A 1959 graduate of San Jose State University, Knowles returned to his alma mater in April to emcee the fiftieth anniversary celebration of its radio-television program. |

3:15 a.m.

Once taping wraps, Oliver and the Up To The Minute staff normally order in grilled cheese sandwiches from the deli down the street, and she reads and prepares for the next day before heading home at 5 a.m. Not tonight, though. Since she’s filling in for Susan McGinnis on the CBS Early Show, it’s time for her to head across town to the studio on East 59th Street.

Walking quickly out to her waiting town car, Oliver says goodnight to the men at the security desk and the door. Once in the car, she inquires after her driver’s new grandchild. He hands back a wallet photograph of the little girl. Everywhere we go, Oliver has a warm greeting for the people she meets.

In the Early Show newsroom, she introduces me to the only other person in the room at that hour, a young production associate, then sits at a computer and begins softly reading the morning’s news stories to herself. Without prompting, the young woman says to me, “Meg’s so nice and down to earth. Sometimes with TV people, they seem nice on television, but then you meet them and ….” She rolls her eyes.

4 a.m.

I follow Oliver into a small recording booth with a heavy door and hold my breath while she records three headlines. Then she walks briskly down the hall to hair and makeup, where one woman works on her face and another blows out her hair before she goes on the set.

The morning news is taped in the CBS Early Show studio, which is at street level and lined with windows and graphic backdrops. At 4:30 a.m., trucks rumble by outside in the dark; inside, it’s quiet and cold under a ceiling of blinding lights. With a producer and two cameramen in front of her, Oliver sits at the news desk reading the morning news, weather, and sports.

I’m perched to the side in one of two wing chairs on a darkened set decorated like a living room—coffee table, fireplace, oil painting over the mantel—marveling at both how extraordinary and how ordinary is this world that Oliver inhabits. While her attractive face and neat summaries of current events are broadcast to viewers around the world, I can see the small electric heater tucked at her feet, the box of Kleenex, and the tin of Altoids just out of the camera’s view.

At 5 a.m., taping finished, Oliver scoops up her coat and purse and we head for the door. In the car, I ask if she’s being groomed for a more prominent news anchor position. She just says she’s happy to love going to work every day.

“I feel so blessed,” she says. “This is my dream job. I just want to continue reporting and anchoring, and covering meaningful stories.”

![]() Patia Stephens ’00, is currently working on an MFA in the Creative Writing Program with a non-fiction emphasis. She is an editor and Web content manager with University Relations and an award-winning writer for the Montanan.

Patia Stephens ’00, is currently working on an MFA in the Creative Writing Program with a non-fiction emphasis. She is an editor and Web content manager with University Relations and an award-winning writer for the Montanan.