Leaders In The Field

UM's Wildlife Biology Program offers unparalleled access to real-world classroomBy Jim Robbins

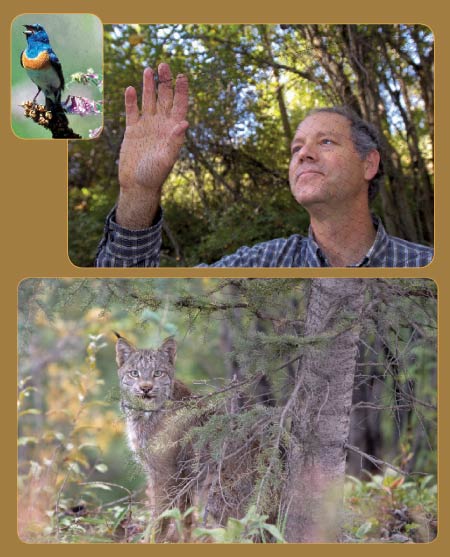

Wildlife Professor Scott Mills with a simple device used to non-invasively collect hair samples from lynx

Researcher Scott Mills hikes the forests and meadows of the Northern Rockies looking for droppings left by snowshoe hares. The DNA in the pellets, he says, will answer a key question—whether the coat color of snowshoe hares is evolving fast enough to keep pace with climate change and fewer days with snow on the ground. “In other words,” he asks, “will the genetic response be fast enough to keep them from being wiped out?”

The answer is a ways off, but the trend does not look good. “They are dying in larger numbers because they are white on more and more days when the ground is brown,” he says.

Mills’ snowshoe hare research is one of many state-of-the-art wildlife studies taking place within driving distance of Missoula. With millions of acres of wilderness and national forest nearby—from Glacier and Yellowstone national parks to the Selway-Bitterroot and Bob Marshall wilderness areas—the University has become the nation’s top school for wildlife research—in the wild.

“The obvious draw for wildlife biologists is right out the door—intact ecosystems and large landscapes,” says Mills, a professor of wildlife biology at UM for thirteen years.

Western Montana is the only place in the lower forty-eight states where all indigenous mammalian species that were present when Lewis and Clark came through are still extant. From grizzlies to wolves, wolverines, lynx, cougars and herds of elk, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats, all of the large mammals still roam.

The ability to study such an array of wildlife so close to campus is exceedingly rare, and Missoula has one of the only university wildlife programs with such ready access to the field. The collection of field data—the behavior and biology of wildlife in the wild—is what makes the program here most distinctive.

“If you are interested in wildlife in the lower forty-eight, Montana is where you want to be,” says Dan Pletscher, director of the Wildlife Biology Program. “Other places read about it. We’re living in the middle of it. We’re grounded in the field, and that’s a big difference.”

Biologists here learn to trap animals, sedate them, take samples, fasten radio collars in place, and track them. These are increasingly the lost arts of wildlife research, says Mills, and scientists at other schools have become more disconnected from the wildlife they study. “It’s the same thing as people not knowing where their food comes from,” he says.

OLD SCHOOL MEETS NEW SCHOOL

The work being done at UM today goes back to the pioneering research of John Craighead, the former head of the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, in whose name an endowed chair recently was created. “A lot of people my age got into the field because of the National Geographic specials showing grizzlies and the Craigheads in Yellowstone,” Pletscher says.

The first graduate finished the program in 1941. In some ways things have changed little. “The old skills are still here,” says Mark Hebblewhite, an assistant professor at UM. That includes cutting logs to build lynx and wolverine traps, constructing log corrals for trapping elk, and tracking animals on the ground.

The old school, though, is wedded to the new. The program here, for example, is the leader in non-invasive research techniques. Biologists use a biopsy dart that scrapes a bit of hide off an elk, for example, for DNA analysis. Or they collect hair from pieces of barbed wire fixed to a tree.

To study songbirds in a less invasive way, UM Professor Erick Greene has identified a unique sonic “fingerprint.” “It’s kind of like jazz,” he says. “Young birds interact with a lot of older birds and learn the riffs. They play around with it and massage it and come up with a song of their own.” (A song by a Lazuli Bunting near Missoula sounds like the childhood favorite “the worms crawl in, the worms crawl out.”) Knowing each bird’s fingerprint allows biologists to identify returning birds by their unique song, instead of trapping them.

“People here are thinking about novel ways to get good data in a logistically challenging area,” Mills says.

Take, for instance, Professor David Naugle, a researcher who uses chemical isotope signatures to glean a wealth of information about his subjects. “You can pull a feather out of a shorebird in Mexico and know where in Canada that bird nested,” Naugle says.

The food and water a bird consumes as it molts—dropping its feathers and growing new ones—is stored as a unique isotopic signature in the blood pulp of the new feathers. When the bird migrates from Canada to Mexico, it carries with it the isotope signature of the region where it last molted. Using the blood pulp, researchers like Naugle can isolate that isotopic signature to identify the latitude at which it normally occurs, and thus where the bird nested the previous season.

The wildlife program also employs modern “eye in the sky” technologies. Satellite imagery allows researchers to take high-resolution images in small areas and make predictions about large landscapes. “The images help us across broad areas,” Naugle says. “That’s key.”

Because of the intact ecosystems and large landscapes in Western Montana, researchers here also can take a “whole-system” approach to wildlife biology. Instead of just researching a predator, for example, biologists look at how a number of species are related to an animal—everything from parasites to amphibians to vegetation.

A COOPERATIVE APPROACH

The unique structure of the wildlife program also makes it different. Similar programs at other universities are housed either in a forestry or agricultural school, where biology is de-emphasized, or in a biology department, where conservation plays a small role. The UM program combines both aspects in the College of Forestry and Conservation and the Division of Biological Sciences. “Students get basic biology, and that undergirds the conservation effort,” Pletscher says.

Lazuli Bunting, such as the older male shown above, are one species of birds studied by Wildlife Professor Erick Greene. Greene (right) checks over the mist net he uses to catch songbirds. Lynx are only one of the many animals researched and studied by Wildlife Biology Professor Scott Mills (below).

The Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, a federal program based on campus, adds a real-world dimension to the Wildlife Biology Program. The Coop Unit brings state and federal wildlife management problems to the University where they are addressed by Coop Unit scientists and their graduate students.

Off campus, the Missoula community is one of the world’s wildlife research and management capitals, a kind of de facto think tank that complements work done by the University. The U.S. Forest Service’s Region 1 headquarters are here, as well as a Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, which conducts wildlife research across the West. A number of top environmental groups have offices in Missoula, including The National Wildlife Federation, The National Forest Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy, while the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, The Boone and Crockett Club, and the Outdoor Writers Association of America are headquartered in Missoula.

“It’s a good place for students to think about how the research connects to the policy,” says Muttulingam Sanjayan, a lead scientist for The Nature Conservancy who teaches in the Wildlife Biology Program.

Students who research grizzly bears or bull trout or wolverines can attend meetings with those who manage the animals and implement the results of their work, Sanjayan says. By contrast, his research on pocket gophers and cheetahs occurred while he was studying at the University of California, Santa Cruz, which he says was hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away from his subjects.

Some of the hottest topics in wildlife biology are in play in the forests and prairies near the University. The Missoula area, for example, is in the middle of the Yellowstone to Yukon corridor, a 2,000-mile stretch of wildland along the Rocky Mountain chain cordillera that biologists, conservationists, and others in the United States and Canada hope to keep biologically intact by fostering connectivity—the ability of wildlife to move between chunks of critical habitat to assure large, genetically secure populations.

Also part of the conservation curriculum is climate change, and it pervades nearly all research at UM. The study Mills is doing in Glacier on snowshoe hares is one example. Assistant Professor Winsor Lowe studies Idaho giant salamanders, which occupy tiny headwater streams in the Bitterroot Mountains. As species try to move up in altitude to keep pace with warming, these critters might be the first to go. “They really can’t move up because they are at the top of the headwaters,” Lowe says. “They are probably most vulnerable.”

Another key aspect of the program here, and a cutting-edge topic in conservation biology, is the importance of the social context in which policy occurs. Managing the wolf biologically is one element of its survival, but how do you take into account the ranchers and hunters and others who have to live with the wolf and its depredations and who, in the end, may be the ones who decide if it survives? Graduate students here have surveyed residents who live with wolves and designed strategies to meet their concerns.

INTERNATIONAL FLAVOR

”We’re grounded in the field, and that’s a big difference,” says Dan Pletscher, director of the Wildlife BIology Program.

An emphasis on field work and a stunning mountain landscape draw students from a number of other countries to UM. About one-quarter of the fifty wildlife biology graduate students have come from abroad to learn the new and the old wildlife techniques. This creates a culturally diverse gathering of those who study the biological diversity. Aspiring wildlife biologists from Pakistan, Poland, Argentina, Taiwan, Italy, Israel, Japan, Scotland, Mongolia, and Bhutan have studied at UM.

The biggest draw, though, is the intact natural laboratory and the fact the mountains here are comparable to places with wildlife in other parts of the world. “The geography is very similar to back home,” says Tshewang Wangchuk, a Bhutanese biologist and UM grad student who manages conflicts there between snow leopards and yak herders. “Being close to nature is as big a part of life in Bhutan as it is here.”

These students bring a sprinkling of international spice to a small city where the sight of elk wandering a meadow or the yipping of coyotes is not uncommon, but foreigners walking the street are a novelty.

“When you are a foreigner here, it is like being from another planet, an object of curiosity in a very positive way,” says Sanjayan, who is Sri Lankan. “In Washington, D.C., no one ever asked me where I was from. Here it happens all the time.”

The Wildlife Biology Program, in fact, has become an important nexus for international wildlife issues and an exporter of high-quality research and conservation ethics to countries around the world. Many of the eighteen faculty members and their students conduct work in other parts of the world. Tshering Tempa, a graduate student, will soon return to Bhutan, where he will become the country’s first professor of wildlife biology. Long closed to outsiders, the Buddhist country has protected its snow leopards, common leopards, pandas, and black-necked cranes. Bhutan is modernizing, however, and pressure on its environment is mounting. Tempa will teach a brand-new corps of wildlife professionals how to keep environmental crises at bay.

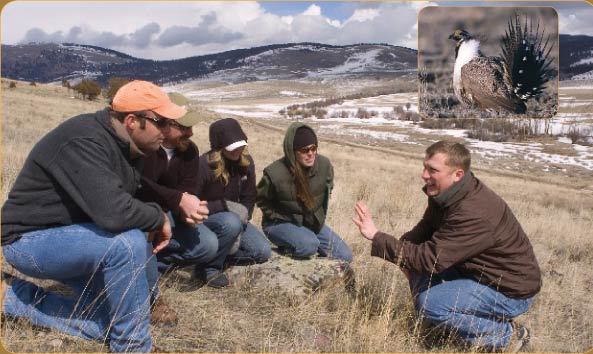

Wildlife Biology Professor David Naugle speaks with students in his field conservation class last month on a field trip to the Blackfoot Valley (above top); A displaying male sage grouse on a lek—a place where males assemble to compete for females in springtime (above).

Sanjayan works with the government of Namibia on the creation of a new type of national park that would integrate people into the landscape so that they can live ecologically sustainable lives raising livestock, managing the park, guiding tourists, and selling crafts. Such sustainable practices are the only way, he says, that people will ever be able to care for the planet. It would be the first park of its kind, in a wild and remote part of the world where black rhinos, lions, giraffe, zebra, and other exotic wildlife all roam.

Part of the appeal for foreign students, many of whom are from rural towns, is Missoula’s modest size. UM has 13,500 undergraduates compared to University of California, Berkeley, another top wildlife school, which has about 32,000 students. There are 225 undergraduates in the wildlife program at UM.

For a medium-sized school, the UM program has a large impact on international wildlife conservation. And learning the science and management techniques in a place where an array of wildlife is right out the door creates a one-of-a-kind credibility—not a “street cred,” but a “field cred.”

“I was in Tanzania talking to Masai herdsmen about predation by lions on cattle,” Sanjayan says. “I knew what they meant. That was stunning to these guys. They think because I am in America I have no idea about big predators. Saying you are from Montana rather than Washington, D.C., makes a big difference when it comes to wildlife.”

Jim Robbins is a freelancer writer in Helena where he writes about science and the environment regularly for The New York Times and Conde Nast Traveler and contributes to other national and international publications. He is the author of three books, most recently The Open Focus Brain: Harnessing the Power of Attention to Heal Mind and Body, published by Shambhala Press.

Jim Robbins is a freelancer writer in Helena where he writes about science and the environment regularly for The New York Times and Conde Nast Traveler and contributes to other national and international publications. He is the author of three books, most recently The Open Focus Brain: Harnessing the Power of Attention to Heal Mind and Body, published by Shambhala Press.