HomeFires

A UM forestry grad saves the day in Missoula.

By Paddy MacDonald

“Low visibility next ten miles,” reads a road sign outside Thompson Falls on a late-August morning. The razor-sharp edges of converging rock, evergreens, river, and sky are dulled under a shroud of smoke that blankets the valley. A train whistle blasts through the vaporous air. Across Main Street from the railroad tracks, sit Krazy Ernie’s Tackle and Bait, Chelsea’s Tea Room, and the Boom Town Bar and Café—all open for business. Down the block, the doors at Harvest Food swing open as yellow-jacketed, heavy-booted firemen file out with sacks of doughnuts and jugs of juice, taking a break from Teepee Creek, ablaze like dozens of other western Montana forests.

“Low visibility next ten miles,” reads a road sign outside Thompson Falls on a late-August morning. The razor-sharp edges of converging rock, evergreens, river, and sky are dulled under a shroud of smoke that blankets the valley. A train whistle blasts through the vaporous air. Across Main Street from the railroad tracks, sit Krazy Ernie’s Tackle and Bait, Chelsea’s Tea Room, and the Boom Town Bar and Café—all open for business. Down the block, the doors at Harvest Food swing open as yellow-jacketed, heavy-booted firemen file out with sacks of doughnuts and jugs of juice, taking a break from Teepee Creek, ablaze like dozens of other western Montana forests.

A few miles north of town, tucked into the woods, lies the Thompson Falls base camp, the brains and support system of the Teepee Creek and Cherry Creek firefighting effort. There’s no drama here. No exploding trees, columns of smoke, or walls of flame. Instead, what you find appears as methodical, organized, and efficient as a well-oiled military base. Trailers circle the area like modern-day covered wagons. Canopies rigged with rope and poles enclose long tables and stacks of supplies. Scattered among the pine trees are multi-colored tents. People in dun-colored clothing dart about like flickers, handing over papers, moving boxes, checking inventory.

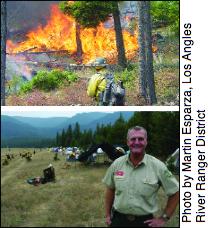

Striding across the dusty ground, clipboard in hand, is Mike Dietrich, the fire camp’s incident commander. If the camp resembles an army, Dietrich is its general. Tall and rangy, shoulders squared, hair cut close, Dietrich’s military bearing has the unmistakable authenticity that comes from experience. He comes to a stop and sweeps a muscled arm in an arc, encompassing the sprawling complex. “This is our home,” he says.

Dietrich, in Montana with his forty-four-member incident management team, is well-schooled in such “homes.” He and his team, based in the Cleveland National Forest in Southern California, are one of several dozen units that participate in a national rotation, spending two weeks at a time in various locations around the country. But this particular assignment has a poignant twist: just before arriving in the Thompson Falls camp, Dietrich’s firefighting efforts were directed amid landscape he once knew well. The hiking paths, biking trails and fishing holes were places he frequented while a student at UM. “I felt some ownership,” Dietrich says of his experience at Black Mountain west of Missoula. “I know how important these places are. I felt emotional—but then, it’s always emotional.”

Black Mountain wasn’t in the original game plan when Team Three was deployed to Montana.

“We were assigned to Cooney Ridge on August tenth,” Dietrich says, “but as we flew in, the situation changed, priorities were reconfigured, and we were re-assigned to the Black Mountain fire.”

Black Mountain, with 650 homes in close proximity, had a tremendous potential for disaster when Dietrich arrived on the scene. His immediate concern was to keep the fire in check by use of retardant planes and a heli-tanker, while he and his team ordered ground crews, bulldozers, and fire engines. “What we needed was to get people and equipment into the fire and go to work,” he says.

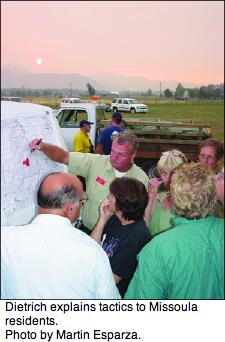

The following evening found Dietrich hosting a community meeting to brief homeowners about the fire’s progress and his team’s firefighting plan. As families from Horseback Ridge, Big Flat, and O’Brien Creek filed quietly into the hayfield west of Missoula, the Black Mountain fire looming in the background, Dietrich found the words he needed to assure the residents that he had a personal stake in protecting their land and homes.

“I am a 1976 graduate of The University of Montana,” Dietrich said after introducing himself. “Go Grizzlies!”

“I am a 1976 graduate of The University of Montana,” Dietrich said after introducing himself. “Go Grizzlies!”

A week-long battle ensued, during which time a horrific windstorm propelled the fire into a run that “exceeded every expectation,” with 300-foot high flames and 30,000-foot columns of smoke, forcing hundreds of residents to evacuate, and burning two homes to the ground.

“Nature was in control,” Dietrich says. Despite the hellish conditions, Dietrich’s team saved seventy-five homes in the fire’s direct path by spraying each with Class A Foam. The crew managed, ultimately, to contain the fire without injury or loss of life to firefighters or residents.

As Team Four took over, Dietrich and his crew moved on to Cherry Creek, near Thompson Falls, to “finish up.” But shortly after their arrival at the new camp, lightening struck yet another region and they suddenly had two fires on their watch. Firefighting, it seems, is not unlike a war, with new skirmishes erupting on a daily basis.

“It’s similar to a paramilitary operation,” Dietrich says, entering Trailer One, which houses the situation unit, the brains of the camp. Inside, men and women tap on keyboards, scrutinize data, bark into cell phones, and stuff color-coded cards into pockets on a nylon bulletin board. Jewel-toned weather maps pulse and quiver from computer monitors. “We meet every night at seven,” Dietrich says, gesturing to his crewmembers. “And a new plan is produced for the next day.”

Around the compound sit the operation’s other necessary components: the check-in and demobilization unit; communication and safety units; the medical trailer, where two EMTs tend to injuries or other health situations; the finance unit, where invoices are signed and time cards recorded; the ordering desk, which can get you “everything you need, from printer cartridges to Tylenol;” and the ground support unit, which schedules buses, SUVs, horses, and pack trains. Off to one side stand shower and laundry facilities.

The smell of simmering beef wafts through the air. “Our kitchen serves 1,500 meals a day, both here at the base and at the spike camps nearby,” Dietrich says. The huge, white-glove-clean catering trailers are ringed with beverage dispensers. Near the menu board, which lists the day’s three 2,200-calorie meals, are bottles of instant hand-sanitizing liquid, stacks of plates, and bins of cellophane-wrapped, plastic silverware. Under the mess tent, rows of cafeteria tables and folding chairs await the next onslaught of ravenous firefighters. In one corner, pink helium balloons hover over a table littered with tiny leather booties and crumpled pink wrapping paper, remnants of a hastily-prepared baby shower.

The camp’s central focus is the supply unit, which resembles a giant, industrial, garage sale. Tables bow under piles of clothing and gear: aluminum tents, Pulaskis, cots, hand tools, and shovels. Boxes and boxes of pants. Five different kinds of tape. Road flares, fuses and cans of Raid. Valves. And thick bundles of hose. “We lay 100,000 feet of hose during a week of firefighting,” Dietrich says.

The camp’s central focus is the supply unit, which resembles a giant, industrial, garage sale. Tables bow under piles of clothing and gear: aluminum tents, Pulaskis, cots, hand tools, and shovels. Boxes and boxes of pants. Five different kinds of tape. Road flares, fuses and cans of Raid. Valves. And thick bundles of hose. “We lay 100,000 feet of hose during a week of firefighting,” Dietrich says.

Dietrich gestures to the jugs of florescent-blue liquid stacked nearby. “This is Class A Foam,” he says, and his eyes take on a new cast. Turns out Dietrich was instrumental in the development of the firefighting tool, beginning in the 1980s with an experiment involving dishwashing liquid. “Dawn was the best soap,” he remembers. By 1992, the firefighting gel used today had been developed, with the help of several other household products. Its basic ingredient was derived from the same material used in disposable diapers. “Those were innovative days,” Dietrich recalls. A ghost of a smile softens his sun-reddened face.

Dietrich’s journey at UM began after he transferred from Paul Smith College in upstate New York. While studying forestry, Dietrich remembers attending a concert or two—Mission Mountain Wood Band and Willie Nelson come to mind—and succumbing often to the lure of the western Montana outdoor wonders he now is struggling to preserve.

After graduation, Dietrich married, fathered two children, and moved to various locales around the country, from New York to North Dakota to Oregon. While working for the Bureau of Land Management in Eugene, Dietrich became involved in fire management and eventually, development of the Class A Foam. He then transferred to the San Bernardino, California, area, which is still his home base. “It’s an intense firefighting environment,” Dietrich says. “And it’s year-round.”

The Thompson Falls base camp is eerily silent—bereft of the 450 firefighters who live here. They arose at 5:30 a.m., showered, ate breakfast, then assembled, coffee cups in hand, for the 7 a.m. briefing before moving out, en masse, to the fires. After a twelve-hour shift, the fighters will return to camp, where they’ll clean up, eat, and, Dietrich hopes, get some sleep.

“The fighters are free to come and go,” Dietrich says, then, after a pause, adds “in theory.” Dietrich’s duties aren’t limited to putting out fires, but extend into population management. “I once had 4,500 in my camp,” Dietrich says, and notes that he’s occasionally had to send fighters home for disciplinary reasons ranging from alcohol and drug abuse to fighting. But his experience in Montana so far has been a positive one, with people he describes as “outstanding.” He also has to stay on top of fatigue management. When Dietrich and his crew deploy in a few days, they’ll have two days of uninterrupted down time, “where we can’t be called,” before being scheduled back into the rotation.

According to Dietrich’s colleagues, his long suit is the ability to communicate with and coordinate disparate response teams and to build relationships by bringing local law enforcement and fire districts into the planning. “I’ve known Mike a long time,” says Greg Greenhoe, deputy director of fire and aviation for the Northern Region Forest Service and area commander of Black Mountain. “He’s an incredible fire manager, largely due to his leadership skills.”

These days, Dietrich and his team manage more and more non-fire incidents, including the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Oklahoma City bombing, hurricanes in Florida and the Caribbean, and typhoons in the South Pacific. They spent two and a half months on the Columbia space shuttle recovery operation. “We recovered 88,000 pieces of the shuttle,” Dietrich says. “That’s 37 percent of the shuttle’s weight—using the same principles as firefighting.” Which is tedious, methodical, work: the team forms a line, each person spread ten feet from another—then they tread the ground, over brush, brambles, and swamps rife with water moccasins. “We recovered objects that were anywhere from flake-sized pieces to an attach ring from one of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters.”

These days, Dietrich and his team manage more and more non-fire incidents, including the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Oklahoma City bombing, hurricanes in Florida and the Caribbean, and typhoons in the South Pacific. They spent two and a half months on the Columbia space shuttle recovery operation. “We recovered 88,000 pieces of the shuttle,” Dietrich says. “That’s 37 percent of the shuttle’s weight—using the same principles as firefighting.” Which is tedious, methodical, work: the team forms a line, each person spread ten feet from another—then they tread the ground, over brush, brambles, and swamps rife with water moccasins. “We recovered objects that were anywhere from flake-sized pieces to an attach ring from one of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters.”

During the recovery effort, Dietrich and his team also happened upon an abandoned vehicle, inside of which was stashed a body—the victim of a year-old murder.

Fire, hurricanes, bombings, terrorist attacks, shuttle recovery, murder. And what does he make of the infinite variety of incidents he manages?

“Sometimes I have no clue,” Dietrich says with a stoic, hard-earned unflappability. “Sometimes I just have no clue.”

Paddy MacDonald, M.A. ’81, is a writer and editor for University Relations.