HOW THE WEST WAS SCRIPTED

"...ain't yu' heard of the improvements west of Big Timber, all the way to Missoula?"

-Owen Wister

The Virginian

By Brian Di Salvatore

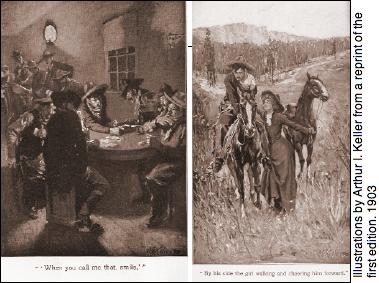

Once upon a teenage time, desperate to escape the drab shadow land in which I felt hideously trapped, I picked up Owen Wister’s The Virginian. I only made it through a few chapters. The handsome cowboy protagonist had not yet married Molly Stark Wood, the plucky gal from Vermont, nor been ambushed and gravely wounded in lonesome terrain. Nor had he been straw boss for the lynching of his former partner, who had taken to brushing dark trails. The hapless, amiable Shorty had not been bushwhacked; the dependable cayuse, Pedro, had not been mutilated by the despicable Balaam, and the craven desperado Trampas, the Virginian’s sworn enemy, had yet to meet his well-deserved fate. (Trampas is the one on the receiving end of one of American popular literature’s most famous—and misquoted—lines: “When you call me that, smile!”)

I didn’t pick the book up again until a few months ago. In some ways, things worked out for the best. It isn’t that the novel is entirely wasted on the young, when most readers engage it. Instead, the book’s multifaceted illuminations and complexity are best appreciated by adults. It’s written for the bifocal set, not bright puppy eyes. Had my reading not been torpedoed by the purloined paperback of Candy a buddy slipped me in fifth-period Spanish, I suspect I’d be stumbling, poorer, through middle age, recalling the book as little more than another rootin’ tootin’ horse opera and not the grand, fascinating novel I now believe it to be.

Weirdly though, the second time around, the book seemed oddly familiar, rife with clichés. That perception, I realized soon enough, is deceiving. Rather than the silty stale-water delta it might appear, The Virginian is a gin-clear headwaters. From it has gushed nearly every element that, rightly or wrongly, constitutes the perceived landscape of the Old West. (At least from a European viewpoint: Wister’s West is white, his Indians cartoonish.)

Its pages hold some of America’s hoariest frontier images: main street showdowns, shifty-eyed drifters, goofy coots, hapless tenderfeet, laconic cowboys, virginal schoolmarms, reined-to-a-stop runaways, God-glorious panoramas, loyal saddle mates, and powerful cattlemen. In short, every ten-gallon in the posse, from Rick O’Shay to the Man Who Thought He Shot Liberty Valance.

If Owen Wister didn’t compose the Code of the West, he certainly wrote its rough draft.

From strange acorns grow wide oaks.

In 1885, one year after Huckleberry Finn declared his intention to light out for the territories, Wister, a twenty-four-year-old mother-tied, Harvard-educated, musically precocious, neurasthenic, high-born Philadelphian, did the same.

In 1885, one year after Huckleberry Finn declared his intention to light out for the territories, Wister, a twenty-four-year-old mother-tied, Harvard-educated, musically precocious, neurasthenic, high-born Philadelphian, did the same.

Huck, whose likely destination was present-day Oklahoma, had had it up to here with “civilizing.” Wister, however, fetched up in now-Wyoming for a prescribed summer “rest cure” on a ranch. Idea was he would regain his balance, hie back East, study law, and cowboy up with the ruling class.

But the law made him cough up hairballs and the dad-blamed fool became a writer. Though his collected work—fiction, nonfiction, biography, political screed—runs to eleven thick volumes, the reputation of that long-ago greenhorn rests solely on a single, patchy novel.

The Virginian, published in 1902, was hardly America’s first cowboy tale—literally millions of Beadle’s lurid dime novels had been circulating since the Civil War.

Wister’s achievement was to brush trail dust off this emerging genre and yank it from the bunkhouse into the parlor: morph “Gun Lords of Stirrup Basin” into “Stagecoach.”

The book was a phenomenon—reprinted six times in six weeks and fifteen times in six months. Never out of print, it has sold well over two million copies—in English, German, Spanish, Czech, French and Arabic, for starters. It became a popular play, several times a motion picture—the first, in 1914, Cecil B. DeMille’s solo directorial debut—and, famously but fatuously, a long-lived television series.

Be warned, the novel’s language often ranges beyond florid. The Virginian, in one mild example, moves “with the undulations of a tiger … as if his muscles flowed beneath his skin.”

As well, its view of womanhood is wincingly traditional. Women are nurturers. They need protection. They are necessary (in unstated ways) and therefore grudgingly tolerated by Wister’s “bachelors of the saddle.” But beware these pushy things, boys: no sooner’n they learn you table manners they’ll try to turn you into some pink-fingered vegetarian.

On the other hand, the book is infused with the modern. The Virginian smokes, drinks, gambles, cusses, plays cruel practical jokes, and has at least one dalliance with a lusty widow. Not to say he doesn’t abide by the Good Book, it’s just that he isn’t some bellerin’ churcher. One of the book’s most winning episodes is his philosophical kneecapping of a pompous circuit rider: Don’t run Sunday on me, preacher man.

Additionally, the lynching scene is raw. (Wister was witness to Wyoming’s Johnson County Wars, in which cattle barons battled those they felt were impinging on their herds and grazing land. These “rustlers,” however, were, in many instances, merely small-beer cattlemen. The sympathies of the patrician Wister lie decidedly with the big-money boys.)

A century old, The Virginian still shines like a new nickel, albeit in ways Wister could hardly have intended: the looking glass into the past becomes a mirror, reflecting our century.

He described his book as a “colonial romance.” And romantic it is: instead of cursing the absence of rain clouds in the night sky, Wister—gooey with the majesty of it all, the tourist who makes his living elsewhere—sees only glittery astral chandeliers.

His narrator—dubbed by the cowboys “Prince of Wales” and clearly a stand-in for Wister himself—is pure rookie. He de-trains, breathing deeply of air “pure as water and strong as wine” and trembles with delight at the easy, masculine camaraderie of the Virginian and his fellow buckaroos.

Our enamored dude immediately disavows his roots; tries in vain to distance himself from his lily-livered fellow travelers. The constant, hilarious belittling of “back east” is one of the book’s abiding pleasures. Even rough saloons, Wister says, tower over their “stateside” counterparts: “More of death they saw, but less of vice…. And death is a thing much cleaner.…”

The Prince sees some newly arrived drummers with re-born eyes, calling their chatter the “celluloid good-fellowship that passes for ivory with … the city crowd.” Noticing a local “character” heading east (to be married, natch!), he asks the Virginian “Are there many oddities [like that fellow] out here?” The Virginian pauses and says “Yes, sir. A right smart of them come in on every train.”

Soon, like moonstruck tourists throughout history, the Prince sets to appropriating “his” discovery, turning things and people into tailor-made commodities. Of the Virginian, he decides “The creature we call a gentleman lies deep in the hearts of thousands that are born without a chance to master the outward graces of the type.”

Here’s where things get interesting. Wister has whisked us into the New West, his narrator some version of that ilk of contemporary Montana arrival who wants it all of a thoroughly authentic piece—the unpeopled vista, the convenient airport and three-star restaurant, the colorful locals—just so it isn’t too, you know, downright authentic. The narrator decries the distance he will have to travel to his summer digs (effectively a dude ranch), turns his nose up at the basic cuisine, and disdains the communal washing facilities. Sure, your nature is magnificent, he says, but can’t you do something about town, that “wretched husk of squalor,” a “soiled pack of cards” whose outskirts are littered with discarded bottles and tin cans and piles of reeking garbage?

The good people of The Virginian all live happily ever after. The narrator, at last, earns his bona fides, becomes a true westerner. We know this because we see him bathing—luxuriating—in the warm waters of nostalgia. The amber casing of his new play land has begun to fog, crack: “This country’s … doomed,” he says, all of several summers under his belt buckle. “The west is growing old.” He might as well have dubbed it The Last Best Place, with every syllable of arrogant, drippy fatalism the phrase suggests.

The Virginian, that noble savage—who like every major character is himself a newcomer— couldn’t agree more. So, reluctantly, he makes his separate peace. By book’s end he is rich, married, a father. There’s nothing left for him to do but cozy up to the hearth of wistfulness, blissfully unaware that he himself has planted the seed of the demon future: “When the natural pasture is eaten off,” he says, “we’ll have big pastures fenced. I am well fixed for the new conditions …. When I took up my land, I chose a place where there is coal. It will not be long before the new railroad needs that.”

Bryan Di Salvatore, M.F.A. ’76, is a freelance writer who lives in Missoula. He won a Grand Gold in a regional CASE competition for his article, “Missoula Now and Then” (Fall 2002 Montanan).