Saving 'Nocksum'

UM alumna Christina Willis works to record an endangered language at the top of the world.

photos and story By Dan Oko

The goats are the first sign that the spring migration has started once again for the Darma people of the Indian Himalayas. All along the winding mountain road that runs alongside the Kali River, separating India from Nepal, families on their way to their summer homes attend herds of shaggy, curly-horned goats, wooly sheep, and supply-laden donkeys. Pavement notwithstanding, this is the route the Darma have followed for generations. If modern life in the form of racing jeeps, motor scooters, and garishly painted “Public Carriers”—India’s ubiquitous trucking fleet—encroach on this annual resettlement, the vehicles have no choice but to idle at pedestrian speeds until the livestock can be herded to the shoulder.

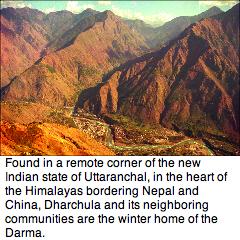

For most of the past year, my partner Christina M. Willis ’96 and I have been living among the Darma in the remote town of Dharchula. In the coming weeks, our plan is to follow the migrating Darma to their villages in the high basins of the Darma Valley on the border of Chinese-occupied Tibet.

A graduate of UM’s Davidson Honors College, Christina has been working toward her doctorate at the University of Texas, Austin, since 1999. Her discipline is linguistics, the study of how people communicate and how language evolved. Christina is trying to help this ethnically distinct indigenous people record their language. Unlike Hindi, the dominant language of northern India, Darma is a Tibeto-Burman dialect that remains strictly oral with no writing system.

Certainly, the Darma language looks like it could be in serious trouble. Out of an estimated population of 4,000 individuals, less than half are reported to speak Darma; children from the community are educated in Hindi; and the young adults we’ve met are more concerned with picking up some English and job prospects in the States than with maintaining the culture of their grandparents.

Certainly, the Darma language looks like it could be in serious trouble. Out of an estimated population of 4,000 individuals, less than half are reported to speak Darma; children from the community are educated in Hindi; and the young adults we’ve met are more concerned with picking up some English and job prospects in the States than with maintaining the culture of their grandparents.

“Development is coming” is a favorite local refrain in Dharchula, although hardly anybody talks about the cost of this progress. According to scientific literature, any language with so few speakers is likely to vanish within two generations.

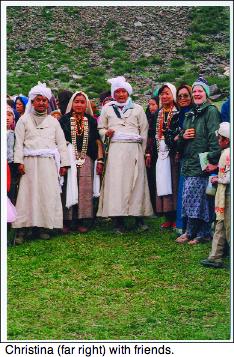

In order to approach this work, Christina traveled twice to India to study Hindi so that she could talk with the locals. Christina focuses primarily on songs, stories, and ceremonies, which provide a window into both the speech and traditions of the Darma people. She attends weddings and funerals, recording songs, stories, and ceremonies and hangs around with a digital recorder to tape day-to-day conversations. “There’s no way to do the research I do without getting into people’s homes to record conversations and stories,” she says. “So even though it’s sometimes been difficult to meet just the right people, I’m feeling pretty lucky to have chosen this topic.”

For members of the Darma community there’s a growing interest in creating a permanent record of their language and culture. “I’ve wanted to make a project like this happen for some time,” says tribal member B.S. Bonal, director of the National Zoo in Delhi. “But we’re happy to have outside help if that’s what it takes to get this job done.”

Often, though not always, “language documentation” deals with languages that are on the verge of extinction. Contact with foreign cultures and economic pressure are two of the most likely culprits for this global phenomenon. Some linguists fear that as many as ninety percent of the world’s languages could be eliminated over the next fifty years. Beyond language-preservation efforts, language documentation provides linguists with the ability to look at the interaction and development of languages worldwide.

Using tapes and direct observation, Christina has been transcribing spoken Darma into something known as the international phonetic alphabet, which enables her to record not just the sounds of consonants and vowels familiar to English speakers, but also any sound made in human language, ranging from various tones found in Vietnamese to the clicking sounds of African bush dialects.

Using tapes and direct observation, Christina has been transcribing spoken Darma into something known as the international phonetic alphabet, which enables her to record not just the sounds of consonants and vowels familiar to English speakers, but also any sound made in human language, ranging from various tones found in Vietnamese to the clicking sounds of African bush dialects.

Christina received a Fulbright fellowship in 2002 and a grant from the National Science Foundation in 2003 to support her work. She is quick to acknowledge the role played by UM professors in her career: Anthony Mattina and Robert Hausmann, professors of linguistics, G.G. Weix, professor of women’s studies, and Katherine “Tobie” Weist, professor of anthropology.

India first cropped up on our radar when a professor in Austin suggested it would be easy enough to find research funds to pay for a trip to the Subcontinent. With eighteen official languages recognized by India’s constitution and some 1,600 additional dialects and regional varieties counted by census takers, Christina realized she would be able to build travel into her research. Having reluctantly agreed to leave Missoula with her for Austin, my only request was that we end up in the mountains. Neither of us had ever heard of Dharchula, thanks in part to its remote location; this geographic isolation, on the other hand, has contributed to Christina’s ability to gain government and institutional support, as well as funding, for her research program.

The haul to Dharchula from New Delhi takes twenty-four hours of straight travel, although only the desperate or insane attempt it in less than two days. Heading out from the New Delhi Train Station, our habit is to catch an overnight coach and then schlep fifteen or so hours in local so-called “shared taxis,” bare-tired, diesel Jeeps driven by eighteen- to twenty-five-year olds who are paid about $2 (USD) per day to negotiate the high mountain passes. People make better time on Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park in August, although I suppose this hair-raising trip could be considered part and parcel of the charm of relocating to the Himalayas.

The haul to Dharchula from New Delhi takes twenty-four hours of straight travel, although only the desperate or insane attempt it in less than two days. Heading out from the New Delhi Train Station, our habit is to catch an overnight coach and then schlep fifteen or so hours in local so-called “shared taxis,” bare-tired, diesel Jeeps driven by eighteen- to twenty-five-year olds who are paid about $2 (USD) per day to negotiate the high mountain passes. People make better time on Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park in August, although I suppose this hair-raising trip could be considered part and parcel of the charm of relocating to the Himalayas.

Living in this remote corner of India, Christina and I have had to reckon with a new set of rules for the road. From the crushing poverty of India’s so-called mega-cities to the ringing temple bells in our own backyard at evening prayer time, there’s no escaping that we’re not in America anymore. The sound of people breaking rock to eke out a few extra rupees each day is the rhythm of our mornings. The hourly bellow of cows in the alley reminds us that whatever industrial development has come to this nation of a billion people, we have landed in a predominantly agrarian community where ancient traditions echo through daily life.

Following the war with China in 1962, the Indian government classified the Darma and two other closely related tribes—the Byangs and Chaudangs—as descendants of Tibetan ancestors. The three groups, however, resist this official grouping—noting their religious practices are an amalgamation of animism and Hinduism, emphatically not Buddhist as in Tibet.

With about 30,000 residents, Dharchula forms the business and population center along our stretch of the Kali River. The Darma, the Byans, and Chaudangs are known collectively as Rang people. Dharchula’s population also includes Indian Army and paramilitary squads stationed to defend the international borders and a host of workers, including a handful of Europeans and Koreans, who are employed at the hydroelectric dam being built at the base of the Darma Valley.

The corridor is dotted with small communities, where the main highway is the only street in town. Shops supply necessities, such as laundry soap, rice, beans, and fresh fruit trucked up from the plains, as well as consumer items such as plastic furniture and Chinese-made handbags.

Away from the road, villages persist where locals tend small farms and orchards on terraced hillsides, growing citrus, potatoes, and grains. Back in Dharchula proper, you’ll find some semblance of indoor plumbing, but throughout the region many people rely on public spigots and natural springs. Open sewers still run through town, while on the outskirts and beyond public latrines remain the norm. Meanwhile, our water only comes on for a couple of hours twice a day, so we must fill buckets for everything from washing dishes to taking showers. Electricity is sporadic, but we have enough energy to keep the laptop charged, and many families have a television.

Away from the road, villages persist where locals tend small farms and orchards on terraced hillsides, growing citrus, potatoes, and grains. Back in Dharchula proper, you’ll find some semblance of indoor plumbing, but throughout the region many people rely on public spigots and natural springs. Open sewers still run through town, while on the outskirts and beyond public latrines remain the norm. Meanwhile, our water only comes on for a couple of hours twice a day, so we must fill buckets for everything from washing dishes to taking showers. Electricity is sporadic, but we have enough energy to keep the laptop charged, and many families have a television.

Despite the availability of Coca Cola, Levi’s, and HBO on satellite television, the cultural divide between East and West continues to hold sway hereabouts; the further you are from such metropolises as Delhi, Madras, and Bombay, the farther behind you leave any similarities between the United States and India. I may have had to surrender my penchant for longnecks and cheeseburgers during our sojourn, but there have been many rewards. Christina and I have come to appreciate the joys of a fine cup of well-spiced chai—sweet tea with cardamom, ginger, and black pepper—not to mention well-seasoned plates of rice and lentils, served with heaping side-orders of cauliflower, potatoes, eggplant, and okra, known in these parts as “subzi masala.”

It’s not just the food that is different. For an American at the edge of the habitable world, as north India has been called, the pace of life, social niceties, and religious practices never once let you forget that this is an exotic destination. In our Himalayan home away from home, we find a certain quietude lost in many Indian and foreign cities, if it was ever there at all, but all the same, day-to-day living can be a real challenge. Thankfully, our Byans landlady operates according to a social code the Rang call “nocksum,” treating most strangers as guests, and guests—even paying ones—as family.

Our shared house is made of brick and cement, a thoroughly modern dwelling by Dharchula standards with its marble floors and indoor toilet, nestled between several houses made of stone and wood. These older homes beyond our glassless windowpanes give a feel for what this place must have been like before development began in earnest. These two-story structures are not much taller than our single-story abode. Most of our neighbors’ living areas are accessed via a narrow wooden ladder-type staircase. The lower rooms housed cattle in the days of yore; now they are used most often for storage. Fewer and fewer of these traditional houses remain.

As befits a community barely a generation removed from village life, hollering for your neighbors is still more common than ringing them on the phone. In our back-street neighborhood nearly everyone is related to our landlady, and she has frequent visitors, often before we are even out of bed. A notable consolation is that we happily receive our daily quotient of “bed tea” while still drowsy and indeed still in bed. It’s a ritual we’ll miss when we return to Texas.

While some old ways linger, other traditions have been mingled with the dominant Hindu practices of the region. Within the first few weeks of arriving in Dharchula, we were taking our daily walk. I had discovered a new trail off the main road. Along the path we noticed a small temple whitewashed on the outside like many we see dotting the hillsides. Following us, a group of local men led a goat to the temple’s small interior shrine, tossed some rice in the air, and said a prayer. Then they chopped the goat’s head off with a sickle and collected some of its blood in a cup. They waved when they noticed us watching.

After a winter in Dharchula, we are more than ready to explore the Darma Valley, the tribe’s traditional summer home. Like a wildlife biologist tracking a rare critter in the backcountry, Christina needs to observe her subjects in their natural habitat. So, after spending a month watching idly while friends and neighbors packed their bags and saddled their livestock, we too finally load our backpacks with sleeping bags, dehydrated noodles, and Christina’s high-tech recording equipment.

It takes us two days of hard walking to reach the open plateau where we will spend most of our time in the Darma Valley. There are fourteen villages located in the valley at altitudes of 8,000 to 14,000 feet that are occupied from May through October. Following the path of the roiling Dhauli River that helped carve the valley, we skirt massive granite cliffs, inch our way across icy glaciers, and cross wobbly wooden bridges over rushing whitewater. We pass through broadleaf forests where oak, Himalayan walnut, and rhododendron trees provide plenty of shade, eventually emerging into sub-alpine evergreen forests where the air smells like vanilla. We share the trail with goatherds, military patrols keeping a wary eye on China, and families joining the migration. Many of the people we meet say they’ve been expecting us; our time in Dharchula evidently has made us a little famous.

We establish a five-day base in the village of Baun, where fortune would have it our friend Mr. Bonal from the Delhi Zoo and other familiar faces can be found. Across the valley, we can see five massive peaks of the Panchachuli Range towering to heights of nearly 25,000 feet. It’s the season for offerings, sacrifice, and feasting, and we join the Darma families as they visit temples and shrines, wolfing down goat meat and rice, and the sweets and fried flat bread called “puri” they pass around. The hills are sprinkled with blooming wildflowers, and every morning we make our way to the river to bathe in the brisk snowmelt.

Christina carries her digital recorder everywhere and tapes Darma folk songs, old men telling stories, and housewives gossiping. She has collected a dictionary of nearly 1,000 words and begun to parse the grammatical rules of Darma. After leaving the valley, she will sit down with consultants to transcribe the tapes and translate the words from Darma into Hindi and English. The idea is that this will form the basis for future generations to learn their language, if it comes to that. Christina takes time to learn the local name for mountain iris and forget-me-nots as well as wild strawberries and various medicinal plants.

In the meantime, we enjoy the Darma nocksum in this rural setting. Many descendents of the village have been away for fifteen to twenty years and this is the first time they’ve had a chance to come back. Many of their children barely speak Darma. We trade stories and snack on blood sausage made from goat intestine and other delicacies. I’m invited to participate in a strength contest involving a very large rock, and when I muscle it onto a platform I am offered a sweet local alcoholic brew. It tastes a little like Mexican mescal, the smoky booze with the worm in the bottle. Again and again, people tell us they’re happy Christina has taken an interest in their language and culture.

When we’ve had our fill of Baun, we take our recording equipment a little further into the backcountry—to the last village in the valley, about fifteen miles away. Past Baun, the villages are more sparsely populated, and many of the small stone houses have been abandoned. The schoolyards boast volleyball nets, but the schools themselves have no teachers. Those who will spend the whole summer and part of the fall in the Darma Valley farm small plots of land or supervise workers who have been brought in to help with this subsistence-level agriculture.

I take these images with me to the States when Christina’s work brings us back to the University of Texas.

Some dream that one day tourists will come and boost the economy of the Darma Valley, but despite the remarkable scenic beauty of this section of the Himalayas, it’s tough to imagine all but the most adventurous making the arduous trip simply to go trekking.

However, in addition to the inherent value of cultural diversity, there are clear economic and environmental bonuses in studying indigenous traditions. The government of the cash-strapped new state of Uttaranchal, for instance, sees a business opportunity in the herbal medicines harvested from this region. But if native knowledge and cultural resources are lost, any number of such assets might disappear as well.

This realization is part of what feeds Christina’s interest in continuing with this sort of work—in fact, we’re heading back to India this winter, so that she can work on completing a dictionary and descriptive grammar of Darma. “It’s a never-ending project, really,” she says. “I mean, I can keep doing this for the rest of my life, and probably there will still be a lot that escapes me. So my goal is to get enough that somebody in the community can eventually take over.”

Dan Oko, former editor of the Missoula Independent and author of Mountain Biking Missoula, maintained a Web log of his trip to India at www.danoko.blogspot.com. His work has appeared in Mother Jones, Outside, and Texas Parks and Wildlife.