Friends of the Flying Fox

UM Students find themselves the “go-to” people in the philippines.By Paddy MacDonald

The cozy, redwood Missoula home where Tammy Mildenstein and Sam Stier now live bears little resemblance to the abode they shared for four years in the Philippines. Oh sure, a couple dozen wild turkeys lurch and stumble around the yard, craning their wattled necks and casting beady-eyed looks at approaching visitors. But as for monkeys, flying foxes, and cobras—once Tammy and Sam’s closer-than-skin neighbors—they exist only as memories and images on Sam’s computer screen. Sam points and clicks, bringing up photo after stunning, exotic photo, while he and his wife reflect on their 1997-2001 Peace Corps experience.

Study in another country

Armed with degrees from Iowa colleges, Sam and Tammy made their way to Montana in much the same way other young people do: through their passion for the outdoors. Although their undergraduate work—Sam’s in communications, Tammy’s in electrical engineering—was unrelated to the environment, they’d both developed an interest in wildlife management. So when they looked at potential graduate schools, UM’s College of Forestry and Conservation seemed a logical choice.

And their sights were broader still.

“We wanted to work in another country, integrate with another culture” says Sam. “We wanted to learn a new language and live with new people.” So they decided to apply to the college’s renowned International Resource Management program, which enhances academic study with a variety of international assignments, including a two-year stint in the Peace Corps.

After spending a year and a half completing the required coursework and specialized study—Sam’s in forestry, Tammy’s in wildlife biology—they began their Peace Corps service and soon found themselves on Subic Bay in the Philippines.

For one hundred years, the United States used Subic Bay as its largest overseas naval base. The base is surrounded by 25,000 acres of tropical forest, which the U.S. Navy used for jungle training exercises and as a buffer between the base and the other island residents. When the Navy’s lease ran out in 1992, the land was turned back over to the Philippine government. By that time, the rest of the island had been cleared for agriculture, and the base’s forested acres suddenly had a unique and increased value. The Filipinos, realizing their opportunity, decided to turn the land into a national park.

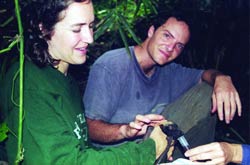

Above, Tammy and Sam reassure a captured bat. Tammy was the first person to catch one of the bats live. Their work has resulted in the Philippine government agreeing to monitor the bats once a year. Below, Tammy and Sam at home in Missoula. |

“They’d heard about national parks,” says Sam, “but they didn’t exactly know what one was.” Sam and Tammy’s assignment was to help the Filipinos conceptualize and build a park. “We had to convey to the people the concept of managing areas,” Sam says. “They thought of a park as having entertainment, like rides,” Tammy adds. “They didn’t see the forest itself as the entertainment.”

The Filipinos, who live in dirt-floored bamboo huts, decided the Peace Corps workers deserved tonier digs, so they ensconced Sam and Tammy in one of the former Navy barracks, a cavernous, crumbling, termite-ridden Quonset hut that once held about forty servicemen.

The cobra

“We were in survival mode,” Sam says. Virtually every item the couple had brought with them became encased in a green fungus within twenty-four hours of their arrival. Spiders the size of sewer grates stomped around the Quonset’s interior, while troops of monkeys banged up and down the hut’s tin roof.

But those critters paled in comparison to the cobra.

During their first week in country, Sam and Tammy noticed a large snake writhing in a corner of their hut. Together they approached the creature, which promptly coiled into a double helix and expanded its neck skin into a hood. “We realized it was a cobra,” Tammy says, “when it began to do its thing.”

The snake posed a dilemma.

“We didn’t know how to get rid of it,” says Sam. “We knew we had to kill it, or it would pop up again someplace else in the hut.” After dispatching the cobra with a machete, Sam went next door to the World Wildlife office, a local organization, to tell them what he’d done. The workers were horrified.

“The people were superstitious and felt that I’d put them in jeopardy,” Sam explains. The office workers strongly suggested that Sam poke the cobra’s eyes out. Why? Because if he didn’t, the workers insisted, the cobra’s relatives would find Sam and extol revenge—on him and the entire village. Sam, despite the menacing glances directed his way, declined, having had more than enough interaction with the cobra for one day.

Cultural differences between the two Peace Corps volunteers and the Filipinos surfaced in other arenas. “The most difficult thing for me,” Tammy says, “was that we were alone on the idea of conservation. The people were used to fighting the environment—including trees, animals, weeds—getting rid of it. Their thinking is different. We Westerners have the luxury of preserving land. The hardest part was trying to sell the idea.”

Sam and Tammy quickly realized that the best way to change the natives’ awareness was to engage them, get them personally involved in the jungle, have them do hands-on projects.

Like, say, count bats.

A conservation ethic

In a ten-acre section of jungle, the couple had discovered a 20,000-strong roost of flying foxes—two-pound bats with six-foot wingspans, called foxes because of their furry, vulpine faces. When not feeding on plants, the bats hang from the trees, looking to the untrained eye like overripe fruit or decayed leaves. The bats are hunted for sport and also because they supposedly taste good—“like chicken”—although neither Tammy nor Sam personally fried any up for themselves. A conspicuous roost, the site was already pegged as one of several five-minute stops for the island’s official tour buses.

But, due to forest clearing and excessive hunting, the bats had become an endangered species. “Ninety percent of the bats were gone,” says Sam. “We wanted to take all the stakeholders—hunters, managers, students, wildlife people—and show them that the bats are a limited resource. We wanted to educate the local communities.”

The couple began a bat-monitoring project and spent much of their time taking the Filipinos with them into the forest, where they observed the bats’ feeding habits and gathered and identified plants.

One afternoon, Tammy needed some help hanging nets in the trees, so she enlisted a group of tiny, indigenous forest dwellers—people she knew had assisted the Navy with several projects. To facilitate the job’s physical demands, Tammy scrounged up all her available equipment—ropes, pulleys, machetes—and combined it into a heap. The forest dwellers stared uncomprehendingly at the pile. After a few seconds, they stripped down to their loincloths, grabbed the nets, and zipped, unaided, into the treetops. “I couldn’t have done it without them,” Tammy says, smiling at the memory.

Sam and Tammy found themselves a constant, conspicuous presence in the area, and quickly became the island’s “go-to” people. A Filipino once brought a dead parrot to the couple’s doorstep, figuring they’d know what to do with it. One morning, a fisherman brought an enormous sea turtle to them, asking for help saving the turtle’s life. The fisherman had already hauled the turtle to Manila and back, and by now, the reptile was dried out and near death. Sam, Tammy, and the fisherman hydrated the turtle, and found an appropriate spot to release it.

Then, still in their “turtle-releasing clothes,” Sam and Tammy were summoned to the Federal Express office, where a conference table of FedEx “suits” asked their advice on bat control. One of the flying foxes had recently flown into a turbine, causing two million dollars worth of damage to the airplane and endangering the pilots. Couldn’t Sam and Tammy move the bats somewhere else?

After convincing the FedEx officers it was possible to work with the animals and suggesting a few re-routing options, Tammy and Sam, in their Tevas and muddy shorts, joined the neck-tied officers for a business lunch.

The locals & the forest

The island’s inhabitants proved a continuing source of wonder, humor, and joy. “The people were absolutely guileless,” says Tammy. “They were fascinated that we were white and assumed that because we were white, we had money. They’d wonder why we came to the island, when all of them were trying to get to America. Volunteerism is a totally foreign concept to them.”

“They were convinced we were with the CIA,” adds Sam. “Or that they were being paid millions of dollars to be there.” Some, unaware that the two were a married couple, were certain Sam and Tammy were on the hunt for eligible spouses.

Each completed their masters theses on the flying foxes—Tammy focused on the bats’ habitat selection and Sam on their dietary habits—and both opted to extend their tours twice.

“It was hard not to be passionate about the forest,” says Tammy. “The forest was what sustained us,” adds Sam. “The tropical wildlife, the parrots, the monkeys—it was so alive it would just hum with life. The jungle was like a giant, complicated clock. It was magical that way.”

Their involvement continues. Tammy recently returned from a six-week stay in Subic Bay, where she’s established an ongoing bat-monitoring network. A few days ago, Sam received an e-mail from a ranger who found hunters going at the flying foxes with fish hooks and wanted Sam’s help.

Settled in their warm, book-strewn home, Tammy and Sam work on doctoral degree professional papers—his on tropical reforestation and hers on population biology—while awaiting the birth of their first child. The Peace Corps days may be over, but the work Sam and Tammy began goes on in their absence.

“For some Peace Corps volunteers, their experience is just a moment in time,” says Tammy. “We got lucky.”

Sam takes another look at a computer image of a bat-laden

tree, then clicks his machine off and gently folds the case.

“It was an honor to be there,” he says. “Such

an honor.” ![]()

Paddy MacDonald, M.A.

’81, is a writer and editor for the Montanan.

Paddy MacDonald, M.A.

’81, is a writer and editor for the Montanan.