Volunteers in Time

A UM alumna finds Peace Corps to be the toughest job she’s ever loved—at 60.By Louise Krumm

Photos By Karen Ramsey

Village chief and local women at a school meeting |

Earlier in the year, Meghan had responded to the soccer pressure by organizing a ten-community girls soccer league in a remote area in western Togo. She “shamed” her friends and family in the United States into purchasing and sending her ten soccer balls and persuaded the shy female teacher in the middle school to coach. Now the girls had an opportunity to show their stuff before the directrice of the U.S. Peace Corps in Togo.

A soccer match

Home team advantage meant the visiting team had to begin its ten-kilometer walk to the game site early that morning. After formal introductions and greetings, the game began. None of the players had shoes or shin guards but Meghan’s home team sported bright green jerseys and a cheering crowd of spectators. Their emboldened coach jogged along the sidelines shouting instructions as her baby, wrapped on her back, peered around the side of her hip to catch the action.

The locals dominated, the school principal’s daughter scoring the winning goal. As the town cheered its winners, the losers began their return trek home under the mid-morning sun. Meghan’s pleasure over the victory was momentary; a new challenge emerged. She was going to have to convince the U.S. manufacturers to make good on their “two-year stitching guarantee” on the soccer balls, which had been worn thin after only six months of practice and play by enthusiastic young African girls.

My husband, Don, and I missed President John Kennedy’s call to join the Peace Corps when we were students at UM in the ’60s. Nearly forty years later, the Peace Corps beckoned. Don had retired from the U.S. Department of State and was working part time on humanitarian and transitional development issues around the world, work he could continue from any country with an airport. I retired from Georgetown University in February 2002 and the next day entered training for a thirty-month assignment as the Peace Corps’ Togo country director.

Peace Corps literature describes volunteer assignments as “the toughest job you’ll ever love.” The slogan proved true for this country director as well.

John Sheffy |

Home in another land

Let me get you oriented. Togo is a tiny sliver of a country in West Africa sandwiched between Ghana and Benin. Both our home and the office were located in Kodjoviakopé, a fishing village-turned-neighborhood in Lomé, the capital. The job of country director brought a refreshing management challenge. There were 140 volunteers and trainees to support, a local staff to manage, governmental relationships to sustain, an office complex, a health unit, and five transit houses throughout the country, as well as a fleet of eight vehicles to maintain. In short, my job was to do everything necessary to keep the volunteers productively engaged, healthy, safe, and supported in villages throughout Togo’s five regions.

Living in Lomé naturally involved immersing oneself in another culture. But, unlike the volunteers, most of whom live without electricity or running water, my administrative job had definite benefits. Our residence was a comfortable four-bedroom house overlooking a lush tropical garden. At tiny stalls along our streets, we could purchase plastic sachets of hibiscus-flavored juice, peanuts packaged in discarded whiskey bottles, locally brewed beer, badly burned fish, roasted plantains, varied canned goods, and even a small voodoo fetish. Market women stopped by the house each day with offerings in baskets—fish, fruit, and vegetables stylistically arranged like giant bouquets of flowers.

Don quickly dubbed Togo “the land of perfect posture” because of the stunning carriage of Togolese men and women. In Togo, absolutely everything is transported on heads—from school children’s book bags to fifty-five-gallon oil drums, irrigation pumps, firewood, water, PVC pipe, sewing machines, ceiling fans, and commercial goods.

During the hot dry season, the sand streets of our neighborhood deepened, and driving was reminiscent of gunning our car through Montana snow drifts. When we became stuck there were no sand plows to help, but local kids knew they could get cent francs (20 cents) for a rescue operation.

| UM and the Peace Corps A continuing source of UM pride is the University’s impressive turnout of Peace Corps volunteers. With thirty-five participants in 2004, UM ranked tenth nationally among medium-sized colleges, ahead of Yale, Notre Dame, and Harvard. One explanation for UM’s hefty numbers can be found in the College of Forestry and Conservation’s International Resource Management program. According to Professor Stephen Siebert, the University’s IRM coordinator, Peace Corps administrators initiated the partnership several years ago when the corps found itself in need of volunteers who were qualified in the areas of wildlife conservation and health care. UM was one of several universities the Peace Corps chose to engage in the mutually beneficial exchange. Once in the IRM program, UM students must complete an interdisciplinary core curriculum and additional coursework in a specific area of academic and professional interest. Next, they must embark on an international assignment. The Peace Corps is one of several choices. “The Peace Corps is popular among the IRM students,” says Siebert, who adds that about seventy-five percent choose it for their assignment. While in the corps, many UM students have effected lasting, positive changes to the countries they visited. • Anna Moline served her Peace Corps time in Paraguay, where she became interested in teaching science using the vegetable gardens common in the country’s grade schools. Seeing ways to integrate the gardens’ scientific phenomena, such as photosynthesis, into the school curriculum, Moline put together a year-long series of educational manuals that are now used all over the country. • While serving the Peace Corps in Bolivia, Verner Kruger documented the cost effectiveness of reduced-impact logging, identified and flagged future crop trees, and laid out road systems. His approaches to a new, improved logging system have been adopted in the Bolivian Amazon basin. |

Volunteers & their projects

Managing the support staff in Lomé was challenging and rewarding, but visits to volunteers in their villages were downright exhilarating. One of my first trips was to visit John Sheffy, a UM graduate student in international forestry and a natural resource management volunteer. John came to Togo through the Peace Corps and UM’s International Resource Management program. When Don and I arrived in John’s tiny village on Togo’s mountainous border with Ghana, villagers directed us down the hill and across the creek to John’s mini demonstration farm. John already had begun construction on what would become a garden, a tree nursery, a maize field, and a fish pond. He was bien integre (well-integrated) into the region where he became known as the American who worked as hard as a Togolese. As villagers watched and worked beside John, they learned about sustainable agricultural practices that included multiple-cropping, composting, organic pesticide use, erosion control, and live fodder fencing.

By the end of John’s two years of service, he had helped his community establish an organic, shade-grown coffee business. Kuma Coffee was the best coffee we could find in Togo. And the shaded habitat in which it grew helped protect the area from deforestation. John also worked with locals to establish poultry raising and bee-keeping co-ops.

To meet his UM requirements, he conducted a case study of three participatory conservation and development efforts. This will form the basis of his master’s thesis, “Village-based forest management in the Togo Ghana Highlands.”

Togo Peace Corps volunteers are assigned to one of four programs—education, like Meghan; agriculture, like John; community health and HIV-AIDS prevention; and small business development. All volunteers maintain a grassroots approach, working with community leaders, families, teachers, and youth to identify and develop sustainable projects that will improve local living conditions.

Lacy Cook and Koranic School students |

Nour Harira

Volunteer Ken Spear was a natural for his assignment in the northern savannah outback. As an American Muslim, he had sought work opportunities in the active Islamic community in Dapaong, the regional capital. His hard-earned fluency in Hausa, the local language, earned him easy integration. Before long he was offering both his energy and expertise to help organize and support an association of Islamic women, Nour Harira. Near the end of Ken’s two-year assignment, U.S. Ambassador Gregory Engle and I were honored guests at the inauguration of a newly constructed Islamic Women’s Community Center. No one was excluded from the singing, dancing, and celebrating—not even the modest young women dressed in their conservative Koranic School uniforms. In Ken’s two years of service, the association had expanded into a network of more than twenty women’s groups that included weavers, teachers, lawyers, market women, and small business operators, all striving to improve the lot of women in the Savannes.

A trash collection system

When residents of Sotouboa asked volunteer Natalie Tabacchi for help in setting up a trash collection system, this high energy woman realized there was no better way to build community pride and improve health conditions in this town of 22,000 population in central Togo. Two thousand dollars from a Small Project Assistance grant provided the incentive and cash for the construction of four trash-hauling pull carts, the purchase of uniforms—shirts, gloves, boots, hats, and summoning whistles—for the ten trash collectors, training for community members and collectors, paint for addresses on each dwelling, and the establishment of a collection and record-keeping system. That was the easy part of the project. Natalie was, after all, a business volunteer.

The hard part turned out to be mapping the entire town before the collection system could be established. Natalie and her counterparts visited every house, held community meetings to come up with names for all the streets, and painted blue numbers on each house.

Last May I celebrated my sixty-first birthday at the inauguration of the trash collection system. The mayor of Sotouboua and I tromped behind the handcarts as the collectors gathered the tiny piles of trash neatly stacked in front of nearly every house. Most residents along this Monday collection route had understood the rules and prepared for the collection. At houses with scattered trash the collectors blew their shiny new whistles, and the surprised occupants were issued stern warnings by the mayor. This program has become so popular that community trash collectors are now cheered as heroes when they walk through the market.

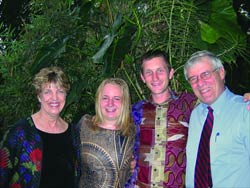

Louise and Don with UM volunteers Kassy Holzheimer and John Sheffy |

Saving a waterfall

Whenever Don and I wanted to be reminded of our hiking days in western Montana, we would trek to the Cascade d’Akloa, where small business volunteer Elisha Moore-Delate and natural resource management volunteer Greg Parent joined forces to promote a magnificent waterfall. Greg worked with local farmers and guides to protect the drainage and rebuild the trail. Elisha worked with the village committee to establish a fee collection and accounting system, an advertising campaign, and a community management board. The success of the project brought a dramatic increase in visitors and an accompanying spike in revenues. However, a two thousand dollar windfall to the community prompted significant disputes concerning how to spend the money, a challenge Greg and Elisha left for the community to resolve.

Hope for tomorrow

All volunteers in Togo include HIV-AIDS education in their work, but health volunteers in the northern “capital” of Kara have taken on a bigger project as they strive to develop a systematic response to this pandemic. Volunteer Kevin Fiori, an epidemiologist, joined with volunteer Peter Davenport, a medical doctor, and volunteer Don Weaks, an architect, to help a small association of people living with AIDS. The Association Espoir pour Demain (Hope for Tomorrow) had received funding to construct a clinic for people living with AIDS. This fledgling organization was overwhelmed not only by the construction project, but also by the challenges of building an association that could respond to the ever-increasing demand for effective services and support.

Using a team approach, Don has been able to oversee the clinic design and construction while Peter advises on medical care. Kevin works with the AED association board to design programs that include counseling, medical care, a food and nutrition program, and assistance for AIDS orphans. The prospect of increased support from the Global Fund drives this group to build the capacity to receive and administer funds that could one day include anti-retro viral medication.

As our tour neared an end, we welcomed our last group of Peace Corps trainees to Togo. Among them was UM graduate Kassy Holzheimer. Kassy completed her eleven-week training program and was sworn in as a volunteer in August 2004, just days before volunteer and UM graduate student John Sheffy completed his two years of service and Don and I boarded an Air France jet for our return home to Washington, D.C.

As we sipped champagne and toasted our adventure, we drew up a

list of Peace Corps highs. We had dusted off our rusty

UM-acquired French; we had lived among the wonderfully welcoming,

hard-working Togolese; and we had been a key part of the support

system that enabled hundreds of Americans, including six

Montanans, to learn about themselves, a very different culture,

and the challenge, complexity, and importance of U.S. engagement

in the developing world. ![]()

Louise Snyder Krumm ’66 was director of the Center for Language Education and Development at Georgetown University before her work with the Peace Corps. She plans to continue working in international development.