That Guy

J.K. Simmons can play the Yellow Peanut M&M, a hysterical editor in an action film, or an über creep on Oz. It’s all in a day’s work. By Paddy MacDonald It’s hot. Boiling, stinking, energy-sapping hot. The temperature in Los Angeles hovers at a hundred and five degrees in my hotel’s entryway, where I’m slumped like an over-dressed sock monkey. Relief arrives promptly at 10 a.m. when a blue Corvette pulls up and J.K. Simmons whisks me away in air-conditioned paradise.

It’s hot. Boiling, stinking, energy-sapping hot. The temperature in Los Angeles hovers at a hundred and five degrees in my hotel’s entryway, where I’m slumped like an over-dressed sock monkey. Relief arrives promptly at 10 a.m. when a blue Corvette pulls up and J.K. Simmons whisks me away in air-conditioned paradise.

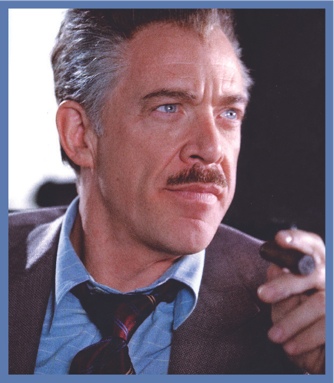

Simmons, a 1978 UM graduate, has established himself as one of those rare birds in Hollywood: a steadily employed actor. Most recently, he’s played J. Jonah Jameson, the mustachioed newspaper editor in all three Spiderman movies. He’s the voice of the M&Ms candy-coated peanut in television commercials. And today he’ll be shooting scenes as Assistant Police Chief Will Pope, a part that was written with Simmons in mind for Turner Network Television’s hit The Closer.

Dressed in a blue T-shirt, khaki-colored camp shorts and a pair of Tevas, Simmons—known to many as Kim—comes off surprisingly un-Hollywood for a veteran film and television actor. He looks like a man on his way to work—if his job was guiding river raft trips. Or coaching Little League, which he does in his free time. But under the Detroit baseball cap Simmons’s craggy, fifty-one-year-old face, punctuated by huge, aqua-marine eyes, is a dead giveaway. It’s him, all right. That guy. “The man of a thousand roles,” according to People magazine.

Steering his car onto the Raleigh Studios lot, Simmons waves at the guard as we pass and soon we’re inside his trailer, an air-conditioned microcosm with a couch, refrigerator, microwave, television, DVD player, full bathroom, change area, dressing table, and lighted mirror. Today’s wardrobe—a dark suit, dress shirt, and tie—hangs in the closet.

Crayoned drawings paper the walls. Snapshots of Simmons’s wife, Michelle, and their children—Joe, seven, and Olivia, five—ring the mirror. Strewn across the table and counter are newspapers and a few magazines—Sports Illustrated and Baseball.

“I sort of stumbled into theater,” he says, not one to belatedly claim a light-bulb moment. The middle child of retired UM music Professor Don Simmons and his wife, Pat, Simmons grew up in Michigan and Ohio. When his father accepted a teaching position at UM in 1972, Simmons soon followed, moving west after completing a year of study at Ohio State University.

Simmons had done some opera while at Ohio State and continued studying voice at UM under the tutelage of music professors Don Carey, Esther England, John Mount, John Ellis, and his father, all of whom he credits for giving him a solid foundation. He had no dramatic aspirations and assumed he’d “end up teaching music somewhere” after graduation.

“I only took one drama class,” Simmons says. His first theater role came along by accident. Between quarters in school, Simmons was persuaded to join the cast in the Missoula Children’s Theatre production of Oliver when the actor playing the knife-grinder “flaked out.”

“Oliver had a great emotional impact on me,” Simmons says.

A staccato knock rattles the trailer and Simmons opens the door to the production assistant trainee, a wiry young man named Nick, whose job it is to keep Simmons up to speed on the day’s schedule. They have a brief conversation before Simmons shuts the door against visible heat molecules. The production schedule is running late.

“There’s a cat in the scene they’re shooting now,” he says, chuckling, “so it’s taking longer.” Kitty, it turns out, is having difficulty playing her part, which involves running down a hallway and onto a bed.

After graduating from UM in 1978, Simmons joined Don Thomson’s repertory troupe at the Bigfork Summer Playhouse, an experience he refers to as “magical.” “There’s an attitude of teamwork there,” he says. “You go to be part of a company, not to be a star. Bigfork was a formative time in my life.” He thinks for a few seconds. “Not just learning how to do it—to be on stage—but to do it without being a diva.”

Simmons next headed for Seattle, where he spent five years, establishing himself as “a musical theater guy” and returning each summer to Bigfork. When Simmons felt like he’d “done all that there was to do” in Seattle he signed on for a Sun Valley, Idaho, production of Cowboy, a musical based on the life of Charlie Russell written by UM alumnus Dick Riddle. “It was a wonderful show,” he says, “and a good fit for me.” Riddle persuaded Simmons to try his luck in New York, and having no responsibilities, no money, and no reason to stay in Seattle, he decided to give Broadway a shot.

There’s another rap on the door. It’s Nick again, who says it’s time for “hair.”

In the hair and make-up trailer, Simmons sits in a swivel chair, ribbing the stylist as she daubs brown dye on his monk’s ring of close-clipped, strawberry-blonde hair.

“I hear you won Employee of the Day,” he booms, and the stylist erupts in laughter. “There are about a hundred and eighty employees on the set,” Simmons explains, “so we each get to be Employee of the Day about twice a year.” Finishing her dye job, the stylist dusts his neck with powder. He thanks her, then leads the way back to his trailer, greeting rigging gaffers, crane grips, and a boom operator as we walk.

“I was twenty-eight,” Simmons says, remembering his cross-country trek to New York City. “I had a Fiat convertible with everything I owned inside and four hundred dollars to my name.” He waited tables and performed in regional theater. “I had no master plan,” Simmons says. “I was just getting confidence that I was where I belonged.” He honed his craft in musicals, comedies, and dramas both new and old, playing the good guy and the bad guy.

Broadway roles began coming Simmons’s way. He understudied Ron Perlman as the colonel in A Few Good Men and played Benny Southstreet in Guys and Dolls. And while starring in Peter Pan, Simmons met his future wife, Michelle Schumacher, who played Tiger Lily opposite his Captain Hook.

Up to this point, theater was all he knew. “I needed a change,” he says. During a Broadway run of Neil Simon’s Laughter on the 23rd Floor, Simmons gave his agent the word: from now on no more plays. “It was TV and film or nothing.” His first big television role was that of a white supremacist on Homicide: Life on the Streets. Then came parts on soap operas—Ryan’s Hope and All My Children—and several other guest spots “whenever they needed a neo-Nazi bastard,” Simmons says. A 1994 gig as the sardonic psychiatrist, Dr. Emil Skoda, on Law and Order turned into an eight-season run and spawned several recurring “Skoda” appearances in assorted Law and Order spin-offs. And Simmons’s neo-Nazi niche led to a juicy part as über-creep Vern Schillinger on HBO’s Oz.

It’s twelve o’clock—time for a read-through of the The Closer’s season finale, which television viewers won’t see until December. Simmons has obtained permission for me to sit in on the reading; however, I must leave before the denouement so I won’t be a security risk. There’s a surprise ending.

The conference room is crammed. Writers, assistant directors, actors, and public relations people mill about, lobbing jokes and trading jibes as they queue up at a buffet table flanking the wall. There’s no dearth of food on the lot. Throughout the morning, I’ve encountered a staggering array of tantalizing setups: a pyramid of glazed doughnuts here; bins of assorted candy bars there; boxes of apples, bowls of chocolate-covered sunflower seeds, and bags of popcorn. But now, since the read-through has been scheduled over the noon hour, the food has graduated from the snack category to . . . lunch. Caterers have delivered stacks of burritos, an enormous bowl of salad, cups of guacamole and salsa, bags of chips, coolers of soda, and bottled water.

The show’s star, Kyra Sedgwick—who’s tiny, wears a sleeveless, bone-colored dress, and is gorgeous—peruses the buffet before loading several helpings of salad onto her plate, much like her character, Deputy Chief Brenda Johnson, would do. Jon Tenney, Chief Johnson’s love interest FBI Agent Fritz Howard, takes a seat, as do G.W. Bailey and Tony Denison, who play detectives Provenza and Flynn. Simmons grabs a Diet Coke, finds his chair, and puts on a pair of reading glasses.

After introductions around the room, the mood turns serious and the read-through begins. Simmons hefts his forty-five page script and immerses himself in the character of Will Pope. The episode, “Overkill,” is a meaty one for Simmons and he milks the lines, causing outbursts of laughter around the table. This is—well—fun. I’m immersed in the plot, fascinated with the process, watching the actors get a sense of their lines. But two-thirds of the way through the script, Simmons slides out of his chair and heads in my direction—uh-oh. He remembers. It’s time for me to leave the room.

Damn.

Half an hour later, the read-through is over. Back in the trailer, as we wait for Simmons’s shooting call, he comments on his experience portraying the quasi-hysterical J. Jonah Jameson—and the relationship between himself and Spiderman’s director, Sam Raimi. “We basically got to the set every day with a couple pages of script to shoot,” Simmons says. “We just used that as a springboard and took off—came up with ideas, ad-libbed, and had fun.

“It’s the most collaborative kind of filming I’ve ever done,” he adds. “Very relaxed, considering the money at stake.” Not only have the Spiderman films gotten Simmons high exposure and higher paychecks, but his face is etched into hundreds of tiny plastic toys. Stores everywhere sell J. Jonah Jameson figures “with desk-pounding action.” Simmons’s face crinkles into a wry grin. “Other action figures get to do things like fly.” Nick announces that it’s time for today’s shoot and Simmons grabs his Will Pope suit and shoes as we head out the door.

Does he ever get nervous? “If you’re prepared,” he says, “if you’ve done your work, then logically you don’t have to be nervous.” As we arrive at the soundstage, Simmons asks me to turn off my cell phone. My camera cell phone. The noise disrupts filming, Simmons explains, and the punishment for cell phone infractions is buying a round of food and beverages for the entire cast and crew.

Oh, yeah, just what they need: more food.

Oh, yeah, just what they need: more food.

Damn. I needed that camera phone. You never know when I may need it to, say, snap a quick picture of Chief Pope’s desk. Or Agent Fritz’s face. I ease into a canvas-backed chair while Simmons disappears into a changing room. Director Charlie Haid—a former regular on Hill Street Blues—sits down beside me. We introduce ourselves and his eyes brighten when he realizes I’m from Missoula. “I’ve got a ranch near Darby,” he says.

As Haid relates his fly-fishing adventures in western Montana, I sneak my eyes sideways toward the ongoing hubbub around us. A purposeful-looking young man eating a green popsicle walks by carrying a lint roller in a plastic bag. A woman, weighed down with multiple headsets and cell phones, with two jeweled pens protruding from a pocket, rushes down the hall. A guy in a Hawaiian shirt rips pieces of fluorescent tape from a roll and presses them over the thick cords that stretch across a doorway.

Simmons strolls out in full police chief mode, oozing Will Pope from every pore. And speaking of pores, Simmons’s skin now sports a peculiar, yellow-orange cast. I comment on the makeup job and he says that the intent isn’t necessarily to make him look better. But what it does, I notice, is bring out those hangdog eyes, those kind, intelligent, seen-it-all eyes.

Haid jumps off his chair and goes to work. “Quiet!” he hollers. “Quiet, people!” A hush falls over the set as filming begins. A cell phone rings. Sweet sufferin’ Abraham! But I’m stunned and grateful to discover that it’s not mine.

“Sorry!” yells Corey Reynolds, who plays Sergeant Gabriel. I’m hoping Reynolds has his wallet. He knows the rules. Later, while the crew sets up for the next scene, I ask Simmons about his ongoing job as the Yellow M&M in the commercials. “It’s a pretty silly way to make a living,” Simmons laughs. “But it’s been paying my mortgage for the last ten years.”

The Yellow M&M wasn’t Simmons’s first choice, character-wise. “I saw myself more as the Red M&M,” Simmons admits. “He was a fast-talkin’, wise-crackin’ New York kind of guy. The Yellow M&M was more of a dumb, slow, sweet kind of guy. But after a ridiculous debate over which character I was better suited for,” Simmons says, “the casting director made her decision. She said, ‘You are the Yellow M&M. J.K., you could kill in this part.’”

Recently Simmons did the voice-over for the M&M’s digital appearance on Entertainment Tonight. And he does other voice-overs, playing two different characters on The Simpsons—the first one as a “gruff editor” of a poetry journal and the second as a “gruff sleazy tabloid editor. They’re both rip-offs of my Spiderman character,” Simmons explains. The Simpsons job is “a real feather in your cap. Especially if you have kids.”

Simmons is called to do the last scene and I watch as he and his colleagues gather in the police interrogation room. The director does a few takes and the action intensifies as Simmons’s and Sedgwick’s characters work with the other detectives to pull a net tighter around their recalcitrant suspect.

Director Haid’s got what he wants. “Last take, everyone,” he says, and the studio erupts in a round of applause. It’s six-twenty-five. The day’s work is over. And that’s exactly what it is for Simmons: a day’s work.

“To be acting because you love it, not to get rich and famous” is what drives Simmons, he explains a short while later over shrimp burritos. “I want to create something lasting, to contribute something worthwhile to humanity—to take people’s minds off their problems for an hour. And my agent is very understanding about that.”

We’re at a hole-in-the-wall Burbank restaurant that Simmons frequents. When we walked in I noticed a couple of teenagers staring at him, like dogs watching meat. They know they recognize him—as Vern Schillinger, J. Jonah Jameson, Garth Pancake from The Jackal, maybe, or T.I. Witherspoon from The Lady Killers, or any one of his thousand roles. They’re not sure, exactly, who Simmons is. But they know he’s that guy.

“The power of saying ‘no’ is a great thing to have,” Simmons says. “I want to have work that’s interesting and satisfying. And I rarely take out-of-town jobs. I want a wife and family.” As the sun sets, Simmons’s thoughts turn to that family. Soon he’ll be heading for home—a five-bedroom, Mediterranean-style house fifteen minutes away in the Hollywood Hills, where the yard, Simmons says, is torn up these days because he’s installing a pool. “I want our house to be the house where all the kids come to play,” he says.

Even after dark, it’s still stifling as J.K. opens my car door and walks me to the hotel’s front entrance. I ask him one more question: How has he remained so balanced, so normal, so—nice? He pauses, those kind eyes focused somewhere in the middle distance as he thinks.

“My success came late in life,” Simmons says, finally. “When I’d earned it and had the maturity to handle it. I was born with good sense,” he adds. “And I was brought up right.”

Epilogue: A month later I’m in Bigfork, prowling the street for a parking place, when I spot a familiar face. It’s J.K., back in town to play centerfield in the Bigfork Playhouse-versus-Townies softball game, an annual event he hasn’t missed in twenty-eight years. “We won . . . after a three-year losing streak,” Simmons reports, “and I received the coveted Golden Slugger Award.”

![]() Paddy MacDonald, a freelance writer, lives in Missoula. Her short stories have appeared in publications including Beacon Street Review, Writers’ Forum, and Seattle Review.

Paddy MacDonald, a freelance writer, lives in Missoula. Her short stories have appeared in publications including Beacon Street Review, Writers’ Forum, and Seattle Review.