From Campus to Combat

by Alex Strickland

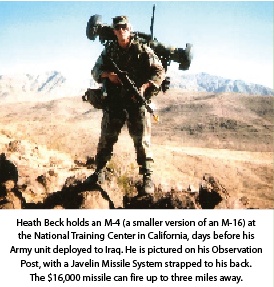

In the back of a little-used desk drawer, Heath Beck’s hearing aid is hidden behind a stack of files and papers. Inside the tiny device are the complicated machinations of a tool that can compensate for the 60 percent hearing loss in Beck’s left ear. It’s a tiny reminder of days spent in the sandy wastes of Iraq’s desert and the booming concussion of a .50-caliber machine gun rattling off rounds from the top of a Humvee. It’s a reminder of the ear plugs Beck didn’t wear because, as a sergeant, he needed to hear the men he led into battle. It’s a reminder of the man that was Sergeant Beck, soldier in the United States Army. It’s not a reminder that Heath Beck, now a successful graduate student at The University of Montana, needs. He remembers.

UM just might have saved Beck’s life.

Beck returned to Missoula from his fourteen-month tour in Iraq in March 2004 and almost immediately put in papers to move his discharge date up from its original September 7 slot. Since UM classes started at the end of August, Beck was able to move the day to July 31 through a “college drop” petition that gives a soldier headed to college up to thirty days before class to move and get settled.

Beck’s unit received stop-loss orders that summer, a “loophole” in the contract, he says, which prevents any soldiers from leaving or transferring out of a unit regardless of when they were originally scheduled to be discharged. The orders for Beck’s unit were effective August 1, 2004. One day later, he left for UM.

It was two years after September 11, 2001, when Beck went to Iraq, three since his mother wept as he told her he’d enlisted and offered consolation with, “When was the last time we were in a war?”

It was the waiting—the knowledge that heading to battle was not an “if,” but a “when” that wore on Beck as the months passed by after America went to war with Iraq.

“It was complete uncertainty,” Beck says. “I wish I could describe the words when you know your unit’s going and you just don’t know the day. It wasn’t being over there, it was the anticipation of going. It was telling your mother goodbye when you don’t know if you’ll come back.”

Once there, Beck, an Army scout, spent his time running reconnaissance on the Iraq-Iran border and later went to Ramadi and Baghdad. He left the service with the rank of sergeant and 40 percent hearing.

“I never didn’t believe in what I was doing,” he says. “But personally, it doesn’t matter what war you fight. It’s not about love of country, it’s about you and your buddy beside you and making sure you get out of there with all your fingers and toes.”

Today, Beck is finishing his master’s degree in accounting from the UM School of Business Administration. He’s the president of Beta Alpha Psi, a business honors society, and fields job offers from major accounting firms around the country. A far cry, he says, from the Iowa farm boy who hated authority before he enlisted in the service seven years ago.

“It’s night and day.”

“It’s night and day.”

The transition from a military Humvee to the classroom has been easier for Beck than some—a respite that he’s made more grateful for thanks to his military experience.

“It put my life in perspective. People got nervous about a big test when I got to college. I didn’t get nervous—the test wasn’t shooting at me. It humbled me and made me grateful for every moment I have here.

“The Army honed my leadership capabilities,” Beck says. “But it’s a part of my life I block out now. There’s Sergeant Beck and there’s Heath.”

For Beck, with a resume of battle-tested leadership and academic achievement, doors are opening. After he starts his accounting career, he’s thinking of attending law school to pursue a degree in tax law.

“If you tell a normal person to move a mountain, they’ll say, ‘You’re crazy,’” he says. “If you tell a combat arms soldier, they’ll ask, ‘Where’s the shovel?’”

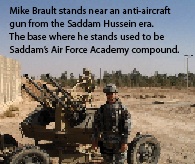

The sands of Iraq exist only in memory for Beck, but they grit the teeth and clog the lungs of Major Mike Brault, a 1996 graduate of UM’s history program. Brault is serving his first tour of duty in Iraq in the eleventh year of a military career that already has sent him to Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan.

Brault is the transportation officer for the Army’s 1st Armored Division, which means his duties include planning, coordinating, and tracking all modes of transportation—aircraft, boats, and ground transport—in an area the size of Georgia that is filled with 22,000 troops.

Born and raised in Missoula, Brault figured out that scholarships were the only way he’d get to college. He says, “I wasn’t good enough at football or have perfect enough grades to get one of those types of scholarships, so ROTC was the best answer.

“As a kid, I always kind of thought I would end up in the military, but I thought it would be the Navy rather than the Army,” he wrote from Iraq. “I guess I saw Top Gun too many times and wanted to be a fighter pilot. Plus, had I gone into the Navy, I would have had to go to school outside of Montana.”

Brault’s days in Iraq begin at 5:30 A.M. and don’t end until almost midnight. During those long, hot hours, he checks all outgoing convoys to ensure they’re packed with the right supplies and headed in the right direction. He has only five officers and soldiers to assist him.

Brault’s days in Iraq begin at 5:30 A.M. and don’t end until almost midnight. During those long, hot hours, he checks all outgoing convoys to ensure they’re packed with the right supplies and headed in the right direction. He has only five officers and soldiers to assist him.

“I spend much of my day putting out proverbial ‘fires,’” he writes. “Everything is a priority and an emergency.” While he was in Afghanistan, Brault spent part of a day tracking down a herd of lambs and goats so some of the allied forces could get a meal.

Though he’s only been on the ground in Iraq for about a month as of this writing, he says life there isn’t terribly different from that in Afghanistan as far as a soldier is concerned.

“The climate is very similar,” he says. “Except that where I am in Iraq is very flat, whereas my location in Afghanistan was very mountainous. It is still very hot and dusty, dust seems to be everywhere.” A recent dust storm left him coated in desert—eyes, nose, everything. “I coughed up black stuff for days.”

Brault says he became a career soldier without even really meaning to at first. One training session led to another, and before he knew it, his eight years were up and he was halfway to retirement at twenty years. He didn’t come from a military family—though he says his grandfather, stepfather, and uncle were all in the service at various times—but he most certainly comes from a Griz family. His mother, Lanell Curry, is the assistant to the UM provost. His wife, Amy, graduated from Missoula with an education degree a year after he did, and his sister, Alicia Felix, and her husband, Jason Felix, are both UM ROTC graduates. Alicia is an Iraq veteran, and Jason is currently on his third deployment there.

Dan DeCoite never could have guessed that his life’s path would take him through Missoula and then into the Army. First, the Truckee, California, native went to play football at Brigham Young University in Utah. After two years he decided he’d like to play with his brother, Dave, again and, as Dan tells it, “UM was the only place that would take both of us.”

And so the DeCoite brothers came to UM in 2000 to terrorize offenses around the Big Sky Conference and cement their legacy as Grizzlies. But Dan’s senior year at UM was remarkable not just for the football, but for what another football player did that changed his life.

September 11th happened while Dan was playing his senior season for the Griz, and not long after that, professional football player Pat Tillman enlisted in the Army, spurning a large contract and garnering widespread media attention.

While at BYU, DeCoite had played against and briefly met Tillman. The NFL-bound player left an impression.

After college DeCoite was playing football for the San Jose Sabre Cats when Tillman was killed in what later emerged as a friendly fire incident.

“I was getting beat up in San Jose,” DeCoite says. “Tillman had just passed away, and that’s what pushed me over the edge to sign on the dotted line.”

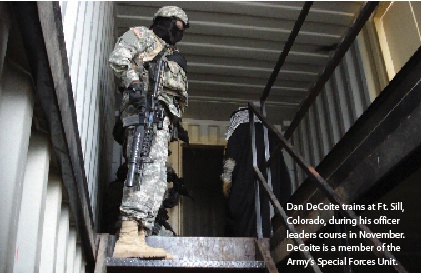

The dotted line brought DeCoite back to UM to pursue a master’s degree and enroll in the ROTC program. He excelled in field tests and exercises, distinguishing himself as the best of his class. As a result, he was chosen to enter the Army’s Special Forces unit immediately upon commissioning—the only 2nd Lieutenant in the country to receive such an accolade.

DeCoite knows he’ll be deployed eventually, but the reality of fighting overseas is still a long way off. The unit he’ll end up with, the 19th group out of Colorado, will have just gone to Iraq by the time DeCoite graduates from his first training and becomes a “deployable asset” on May 2. That leaves him with almost two years for the Army to train him. He will attend the Airborne and Ranger schools, military intelligence school, and “whatever other schools” they send him to, he says.

When it’s all said and done, DeCoite will be a Green Beret, part of one of the most specialized and elite fighting forces on the planet.

“Some people are happy with what they do,” he says. “If I was working for somebody, I’d want to be manager or owner. I don't like knowing there's something better I didn't try for.

“To me the opportunity to do something like the military or Special Forces is the same thing as playing at UM. They're the best; you want to be part of the best, and be associated with the best.”

By Cary Shimek

VIETNAM - RICH MAGERA

Rich Magera remembers the day his hometown of St. Regis felt the farthest away.

It was 1967 Vietnam, and the young Army sergeant was sent to Saigon for supplies. Driving his vehicle down a crowded street, he saw a little Vietnamese girl selling flowers twenty yards away. She suddenly pulled a string and detonated the hidden explosives she wore, killing herself and five nearby GIs.

“A combat zone is not a nice place,” says Magera, now superintendent of Plains High School. “There were a lot of heinous things that went on.”

That wasn’t his only experience with suicide bombers. One night the Viet Cong struck the Tan Son Nhut Airbase where he worked. They destroyed several U.S. aircraft using mortars and satchel-charge-carrying soldiers who blew themselves up.

“Most military guys will tell you that being in a combat zone is hours of boredom interspersed with moments of terror,” Magera says. “You don’t have time to think, things suddenly just happen.”

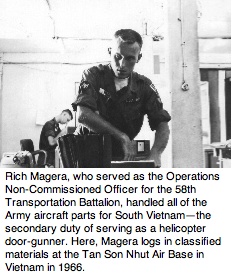

Magera served as a helicopter door gunner, guarding soldiers and supplies flown to and from the field. He often raked tree lines with bullets during landings and take-offs to ensure nobody was there. Sometimes the fire was returned.

“Getting shot at is an odd experience,” he says. “You aren’t looking for the bullets coming at you, and they come in too fast to see anyway, but afterwards you feel drained coming down from that adrenaline high. I never got shot, but the choppers took some bullet holes.”

After returning to the States, Magera found that “fireworks made me crazy.” He attended UM from 1969 to 1975. He said his time in Vietnam made him appreciate his country more, and he rolled his eyes when hearing fellow students complain about registering for classes, professors or trying to get a paper done. They could be in the jungle.

He earned his ROTC commission from UM in 1974 and stayed in the military until 1993. He commanded UM’s ROTC Grizzly Battalion during 1981-84. He then returned as a major and served as executive officer during his 1988-93 tour.

Magera admits his opinions about ’Nam change daily, but he has a favorite memory: “Getting on the airplane and leaving.”

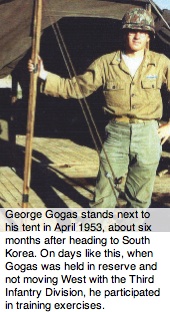

KOREAN WAR - GEORGE GOGAS

By the winter of 1951-52, Lynn Erb of Billings had a hard time focusing in her UM classes. That’s because her fiancé, a Missoula boy named George Gogas, had been sent to the Korean War. Gogas was a 1951 UM graduate with an art degree and ROTC commission.

By the winter of 1951-52, Lynn Erb of Billings had a hard time focusing in her UM classes. That’s because her fiancé, a Missoula boy named George Gogas, had been sent to the Korean War. Gogas was a 1951 UM graduate with an art degree and ROTC commission.

“It was sad and depressing,” she says. “It wasn’t easy to concentrate on what I was doing. But George was good about writing, and I would write him back. It helped get us through.”

That winter Gogas and his Army company found themselves guarding the 3,400-foot rim of a circular valley called the Punchbowl. It was Montana-cold atop the ridge, where they lived in trenches and bunkers. Strategic points such as the Punchbowl and the nearby Heartbreak and Bloody ridges had been purchased with many soldiers’ lives before Gogas arrived as a replacement.

“The enemy were North Koreans,” he says. “They shelled us, and we shelled them. Then we’d duck into bunkers. It wasn’t much fun, I can tell you. We also sent out patrols every night. We only went out 100 to 150 yards—just to let Charlie know we had a presence there.”

He became executive officer for the company commander. His duties included running the command post at night and keeping in radio contact with the patrols. Despite the shelling, they only suffered three casualties in three months atop the ridge, and those came from friendly fire accidents.

“One night we were sending out a patrol, and one of our guys was helping another guy put on an ‘overwhite’—a camouflage white parka that went over our (regular) parka. Anyway, one guy was holding his weapon between his knees as he helped the other guy. His automatic weapon slipped—we called it a grease gun or burp gun. It hit the frozen ground and recoiled. It fired big .45-caliber shells, and one went right in his body.”

When Gogas made it home, he married his sweetheart and taught high school art in Missoula for 28 years. He also raised a son, trained and showed champion quarter horses, and became a prominent painter. UM has some of his works and did a retrospective on him in 2002.

“I was really glad when he came home,” Lynn says.

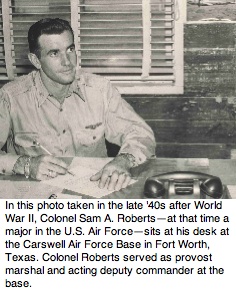

WORLD WAR II - SAM ROBERTS

Before Sam Roberts helped put the finishing touches on World War II, he was a UM football hero.

Reared in Helena, Roberts attended campus on an athletic scholarship from 1937 to 1941. The rugged player developed matinee idol looks, even though his nose was broken three times in the leather helmet days before facemasks. A business major who excelled in ROTC, he soon was named the cadet commander of the campus battalion. He fondly recalls marching on UM’s Oval or spending time with his Sigma Chi fraternity brothers—twenty-four of whom wouldn’t return from the conflict about to engulf the world.

After war broke out, Roberts excelled at training bomber pilots and bombardiers in New Mexico. Many of those flew their twenty-five missions and returned from battle with medals and stories of survival. Roberts ached to practice what he preached, but his colonel wouldn’t release him for combat duty unless he graduated 400 certified bombing pilots without an accident. When Roberts accomplished that, his colonel sadly asked, “Can I talk you out of it?” No, sir.

So in August 1945, the UM grad found himself commanding a B-29 superfortress in the night skies above Japan. Painted on the side was: “The Grym Gryphon—the Nipponese Night-mare.” She was among 250 planes flying in formation toward the last energy system in northern Japan. A few days earlier the world had entered the atomic age with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but the Japanese still hadn’t surrendered. The Gryphon was now part of what would be the last bombing run of the war.

Flashes were soon seen in the darkness about them. They meant a rocket or kamikaze plane loaded with explosives had found a U.S. target. Roberts got on the microphone and told his nine-member crew, “Steady. Steady, everyone. No change.” Then he gritted his teeth and said a little prayer. They couldn’t take evasive action until after dropping their ten tons of bombs on the target.

The B-29s did knock out the energy plant, but the Gryphon didn’t have enough fuel to return to its home base. If forced to ditch, all crew members had agreed they would fight to their last bullet—which like the Lone Ranger’s was painted silver—and that one they would use on themselves to avoid Japanese torture. But they were able to land on a new runway on Iwo Jima, and Roberts admits to hugging a marine who helped build it.

Colonel Roberts served with distinction during a lengthy military career. By 1967 he was a top administrator in Vietnam, and he briefed presidents Kennedy and Johnson. He retired in 1970 with more than 7,000 flying hours.

“We have many things to be thankful for,” says the 89-year-old with a bruising handshake. “Do you have a flag at home? Do you know what it stands for?”

UM's ROTC Program Among The Best

Sitting on the other side of campus from the gleaming Gallagher Business Building and

the brand-new Anderson Hall, UM’s ROTC program has quietly built itself into one of the finest in the country, despite its less-than-modern home.

Tucked away in the bottom of the Schreiber Gymnasium is the fifth-ranked ROTC program in America, responsible for producing more than 1,800 Army officers since its first cadet graduated in 1922.

The success of UM’s program comes as no surprise to Helena native Major Dean Roberts, the battalion’s enrollment officer. Montana has the highest rate of military service per capita of any state in the nation —between 5 and 6 percent.

“There are 100 cadets in the program,” he says. ‘We’re the second largest in the Pacific Northwest and very close to passing Washington State University.”

Roberts also is quick to point out that the average cadet GPA is 3.55.

“Our numbers are higher than they’ve historically been,” he says. “Kids today are raising their hands to volunteer knowing they’re going to be in a bad place. We’re at our largest levels since World War II. That’s unique in an era of complete volunteerism.”

Up until 1974 ROTC courses were mandatory for every male student on campus.

“We’ve got 23-year-old kids who have already been deployed for three years,” he says. “They come back and say, ‘Well, I’ve got to get serious about school now.’”

Roberts and his boss, Whitehall-raised Lieutenant Colonel Michael Hedegaard, have long wondered how the quality of cadets in the program has remained consistently high, and the answer they’ve come up with is that 85 percent of them are from Montana.

“They grow up in this state, and they understand hard work and leadership and motivation,” Roberts says. ”They knock on our door and say ‘It’s what I want to do.’”

He sees that sort of understanding in the military science courses he teaches to regular students and his cadets, who have more knowledge of the world and maturity than previous generations.

“They have more maturity than I did at that age, and I’m a West Point graduate,” he says. “I went because they paid for school and had a great wrestling team.”

Roberts has a different take than those who have labeled today’s young people, in their world of iPods and MySpace, a “lost generation.”

“I think this is the next greatest generation.”