Young and Restless AT UM

By Paddy MacDonald

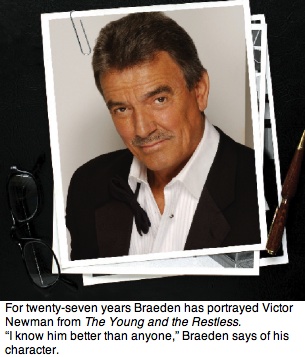

Followers of daytime television’s popular soap opera, The Young and the Restless, both adore and despise the show’s linchpin character, Victor Newman—a brilliant, suave, womanizing, company-stealing captain of industry. Newman, also known as “The Black Knight” and “Mr. Mustache,” has been portrayed from the character’s inception by actor Eric Braeden. Many 1960s-era UM alumni may recognize Braeden as Hans Gudegast, a dashing student from Germany who threw discus on the track team, dated classmate Dorothy McBride, marched in daily ROTC drills—and pulled green chain at Bonner Mill in his spare time.

I don’t know what to expect as I approach Braeden’s dressing room at CBS Studios in Los Angeles. His alter ego, Victor Newman, has been shot, poisoned, spear-gunned, kidnapped, and presumed dead. But—this is the scary part—you should see the other guys. Victor Newman prevails. Always. He pursues his enemies with Captain Ahab-like monomania, never letting up until he’s exacted revenge.

So I’m hoping Mr. Eric Braeden wasn’t typecast, if you get my drift.

As I enter the room, Braeden sets aside the script he’s editing, stands, and introduces himself, his elegant voice mesmerizing with its slight Teutonic cadence. Tall, fit, and casually dressed in jeans, black jacket, and Rockport boots, Braeden radiates a magnetic force, much like the character he plays. But Braeden is younger-looking and more handsome than his television doppelganger. The brown eyes are larger, warmer—and they lack the sinister, heavy-lidded cast that can send a Victor Newman adversary screamin’ for his mama.

Originally from Kiel, West Germany, Braeden was born during World War II,the third of four boys. The trauma of growing up amid post-war destruction forever shaped Braeden’s character, ripening him into atough-as-leather survivor with a sensitive, vulnerable core. As a child,Braeden escaped into the world of Karl May’s Wild West novels.“Every German boy read them,” Braeden says. “So I was deeply steeped in that lore.” Fascinated with the cowboys-and-Indians stories, Braeden developed an early yen to see America.

At age eighteen, Braeden left home for the United States, first spending afew months in Galveston, where his cousin taught at the University of Texas.Braeden’s cousin connected him with a fellow German—a man in his eighties who ranched near Florence—and soon Braeden boarded a Montana-bound Greyhound bus to become a ranch hand.

“August Hermberg picked me up in a brand-new Chevy,” Braeden says. “I’ll never forget that new car—I was very impressed with that Chevy. All I wanted to do was drive cars . . . .” Braeden leans back and folds his arms, lost for a moment in that inexplicable world of men and automobiles. “So,” Braeden continues, “August Hermberg drove me out to the ranch where I met the rest of the family and the foreman. The next morning about five or five-thirty I got up, had breakfast,and was assigned a horse. We fixed fences . . . and we baled hay.”Having grown up in Germany’s farm country, Braeden was used to hardwork. “I earned my living as soon as I was old enough to carry things,” he says.

An accomplished athlete—Braeden’s prowess in javelin, discus,and shot put had helped his team capture the German Youth Championship in1958—he won a scholarship to UM. But Braeden still had to earn a living, so he worked at Bonner Mill from six P.M. until two in the morning.With the job, academic studies, ROTC drills, and track team, “I slept for an average of—who knows—four or five hours a night.”

Braeden rented a room near campus and later lived in the Sigma Phi Epsilonhouse. He remembers humanities Professor Leslie Fiedler as a dynamic lecturer and wishes he’d had more time to study. “I was enormously curious, intellectually,” Braeden says, “but I was exhausted and had no time to do anything . . . the luxury of having your living expenses paid for and just studying—my God, I used to dream of that.”

Braeden’s only UM acting experience came when friends convinced himto try out for The Cherry Orchard. After winning a role, though, Braeden was forced to turn it down when he learned of the extensive rehearsal schedule.

Life changed radically for Braeden when he met up with fellow student Bob McKinnon. “He was one of those Hemingway-esque characters, a tough guy,and very bright,” Braeden says. McKinnon had a plan: to take a fifteen-foot, forty-horsepower motorboat both up and down the Salmon River. McKinnon found a sponsor—Johnson Motors—and Life magazine was showing interest in the project. But McKinnon couldn’t convince anyone to accompany him on the journey.

Until he proposed the idea to Braeden.

“I said, ‘What’s the upshot?’ and McKinnon said,‘We’ll make a documentary and take it to California,’ and Isaid ‘I'm in!’” Braeden laughs. “It meant adventure,and no one had ever done it before.” Braeden and McKinnon put in near Lewiston, Idaho, attended by the press and local officials. “The Chamber of Commerce people said, ‘Do you know what you’re getting into? Because people have died doing this stuff.’ And I said,‘Let’s go!’ At that age you don’t register.”

At first, Braeden felt like he was on vacation. “I said, ‘This is nothing’—until I heard a certain noise, and it became more cacophonous as we came around the turn. I said, ‘What the hell is that?’ Well, it was the first rapid. It was a rather spectacular moment, and had I had a chance to get out of it then, I probably would have.But my pure male ego said, ‘No, I’m not going to give in. If he’s not going to turn around, I’m not either.’”

A professional cameraman documented the trip, although he missed the most exciting segments, including the three times Braeden found himself close to death. “When you get past the rapid and you think you’re over the hump,” Braeden recalls, “that’s when it gets dangerous. Once you get through the washing machine, then you hit the rocks. I barely survived that thing.”

By the time Braeden and McKinnon pulled to shore, they’d missed the Life magazine deadline, but they finished their documentary—TheRiverbusters—and headed for L.A. “We showed that film on varioustalk shows, and we were taken around by a public relations man from J. WalterThompson,” Braeden says. Eventually, McKinnon returned to Montana for family obligations and Braeden, with five hundred dollars from Johnson Motorsin his pocket, stayed on.

Braeden parked cars, moved furniture, and earned ten dollars a gameplaying soccer for La Scala, an upscale restaurant where he also bused tables. He joined a semi-pro soccer team and studied political science at Santa Monica State College, where he met his future wife, Dale Russell.“She went to a Catholic school,” Braeden says, and “was well-educated, very steeped in European literature . . . so there was an affinity.”

As Braeden speaks, I’m hearing a timid but insistent knocking. Go away, I’m thinking, as I send waves of hate molecules toward the door.Then I worry that this is a planned interruption. After all, Eric Braeden’s a busy guy. Perhaps I’m about to be sent on my way. But a puzzled look flickers across Braeden’s face. “Who is that?” he says. Tap, tap, tap. Braeden raises an eyebrow at the noise,which by now sounds to me like a definite . . . pummel. Then Braeden springs panther-like from the couch, and I’m suddenly witnessing a Victor Newman moment.

“Who the hell is knocking on my door?” Braeden says, crossing the room in two strides and ripping open the door to reveal a hapless, paper-burdened assistant. “Put that in my mailbox!” he commands, then returns to the couch, sits back down and rubs his brow.“Okay,” Braeden says, smiling, and his eyes crinkle at thecorners. “Where were we?”

Oh, thank you. Thank you.

While still in school, Braeden heard that Hollywood needed German actors—so he got an agent and was soon appearing in television showsand in films. In 1962 Braeden landed the part of Captain Dietrich in the television series The Rat Patrol, which ran for two seasons. When he got astarring role in the movie Colossus: The Forbin Project, Braeden was stillusing his given name, Hans Gudegast. But reluctantly, under studio pressure,he changed his name—later calling the decision one of the most difficult of his life.

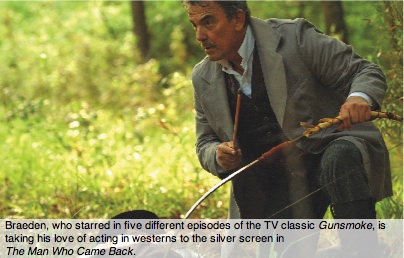

Opportunities increased exponentially, and Braeden worked with actors such as Marlon Brando, Janet Leigh, and Roddy McDowell, racking up more than 120 appearances in films, made-for-TV movies, and television series—playing such diverse characters as a “bad-ass” on Gunsmoke, an acerbic movie critic in The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and Colonel John Jacob Astor in the Oscar-winning epic, Titanic.

In 1980, Braeden signed a three-month contract to portray Victor Newman on The Young and the Restless. His character immediately resonated with audiences, and Braeden signed on—albeit reluctantly—for another hitch. And another. “I wanted to leave after the first year,” he says. “I didn’t like it at all.” Braeden felt “emptied out” playing bad guys for so many years and wanted the chance to develop a more multifaceted character. The producer and head writer listened—and soon gave Victor Newman a tragic past and some emotional depth. When Braeden read the new scripts he realized, instinctively, that he’d stay on indefinitely. “So I will always be grateful to this show,” he says, “for giving me the chance to show other sides to what makes up Eric Braeden—and Victor Newman, to some extent.”

The show’s writers have drawn liberally from events in Braeden’s life, including childhood traumas. “My father died when I was twelve,” Braeden says, and tears spring to his eyes, surprising him. “It was the greatest loss of my life, you know,” he says, swiping each wet cheekbone with a fist.

The writers also incorporated Braeden’s talent and training as a boxer into the show, often featuring the character diffusing energy —or ramping it up—by working on thebag in the Newman ranch’s tack room. “I used to box in the ghettos,” Braeden says. “I have enormous respect for boxing. An old black boxing trainer told me, ‘It’s like walking through fire,’ and he’s so right. It tests you. To the core.”

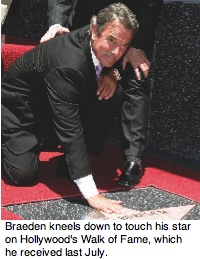

Braeden’s acting has garnered him enormous recognition, including a People’s Choice Award, an Emmy, a special honor at the thirty-eighth annual Monte Carlo Television Festival, and most recently his own star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, which Braeden received in a ceremony last July. “That was a…very, very deeply moving moment,” Braeden says of the event, which drew hundreds of fans and friends.

Taking his first run at producing, Braeden made a film last summer, The Man Who Came Back. The movie, starring Braeden and featuring George Kennedy,Armand Assante, Sean Young, and boxer Ken Norton, is set for release this year.

“I enjoyed it enormously,” Braeden says of making the film.“It’s very challenging . . . When you work as an actor, usually,you only do what you do. But when you produce, you are in charge of everything. I like to be in charge.”

Off-camera, Braeden plays tennis, does Olympic weight-lifting, and enjoys life at home in Pacific Palisades with Dale, his wife of forty-two years.They’re a close family—the Braedens spend as much time as they can with their screenwriter son, Christian, daughter-in-law, Stacey, and granddaughter, four-year-old Tatiana. “I adore her,” Braeden saysof his granddaughter, laughing. “You find yourself doing things . . .crawling around the floor . . . I’ll do anything she says.Practically.”

Asked how he’s managed so well in a profession with astronomical odds against success, Braeden smiles, his eyes crinkling again. “I grew up tough,” he says. “I’ll fight you to the last—I’ll never give up.” Never give up? Sounds just like something Victor Newman would say. And Eric Braeden would be the first to agree.

[Editors Note: Eric Braeden will visit UM this spring to screen his upcoming film, The Man Who Came Back. Details, as they become available, will be posted on the UM Web site’s Newsroom at: www.umt.edu/news]