The State of Higher Education in Montana

As the economy continues to dip, more people of all ages are making the decision to invest in higher education.

By Jacob Baynham

UM President George Dennison looks out on the Oval from the steps of Main Hall.

When Kendra Cousineau, nineteen, entered her first semester of the pre-journalism program at UM last fall, the U.S. economy was headed for its most dramatic downturn since the Great Depression.

To cover the costs of life and a college education, Cousineau works two jobs at seven dollars an hour—she’s now looking for a third—and lives between Florence and Lolo where rents are cheaper. The half-hour commute to campus in Missoula isn’t as bad now that the price of gas is down. On a good day, ten dollars will get her half a tank.

Until classes began in August, Cousineau was debating if it was a smart time to leave the work force as a waitress and become a student. In the end, the choice to go to college won out.

“I was worried about how I was going to pay rent,” she says. “But I knew if I didn’t go now I probably never would have.”

It hasn’t been easy. Cousineau works thirty-five hours a week while holding down a twelve-credit course load. Spring semester she’ll have sixteen credits.

“I’ve pretty much become an insomniac,” she says. “I think that there should be other means out there for me to pay for school, but since there isn’t, I guess I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do.”

For now, that means juggling jobs, lectures, and studies. It also will mean graduating with at least $14,000 in loans. “It’s definitely scary,” she says. “But in the long run, I think it’s worth it. You just hope you get a good job.”

For all the fright tough economic times bring to employees, businesses, and banks, they can be a boon for colleges and universities, which often see enrollment figures rise during financial slides.

Kendra Cousineau fills her vehicle with gas. She makes a half-hour commute to campus so she can save money by living where rent is cheaper.

“What you sacrifice in going to school is the money you spend on tuition and books, but most importantly it’s the money you’d be making out of school,” explains retired UM economics Professor John Photiades. “When there is a recession and job options decrease, more people tend to go back to university.”

While admissions personnel say it’s too early to attribute it to the financial crisis, enrollment levels in the Montana University System are rising across the board, especially in the two-year, career-track programs of the colleges of technology.

But the challenges remain tall. With depreciating university endowments, fewer state funds, wary lenders, thriftier prospective students, and declining numbers of high school graduates, no one is sure of the future that awaits higher education in Montana. Perhaps only one thing is certain: College today isn’t what it used to be.

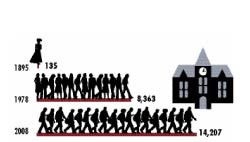

Jed Liston, assistant vice president for enrollment at UM, is generally a positive man. This year he has cause to be even more upbeat than usual. Sitting at a table amidst the whir of phone calls and tapping keyboards of the admissions staff, he rattles off the fall 2008 enrollment figures: 14,207 students and an incoming freshmen class of 1,868. “It’s the highest we’ve ever been,” he says. “We’re very proud of those figures.”

For the admissions and enrollment staff, the record numbers are the fruits of a lot of labor. Surrounding Liston are a half dozen empty offices belonging to recruiters who are on the road throughout the state and nation, looking to encourage more high school graduates to study at UM.

“Our mission is to get the quantity of students we need at the quality the campus deserves,” Liston says.

Student quantity is a lot more important to the vitality of a university than it was when Liston first came to UM as a student of speech pathology thirty years ago. At that time, UM’s enrollment was scarcely more than 8,300 and the University received forty percent of its funding from state appropriations.

Now the tables have turned; UM secures only thirteen percent of its funding from the state and increasingly relies on tuition dollars to offset costs. Record enrollment levels enable the University to keep pace with its development goals.

The manner in which these students get their degrees also is changing. When Liston speaks in front of alumni gatherings, he asks audience members to raise their hands if they were able to pay for their degree by working as they studied. “Only the older alumni raise their hands,” Liston says. “If students now were to fund their way through college like they did before, the minimum wage would have to be thirty-two dollars an hour.”

Financial Aid Director Mick Hanson (left) discusses a college payment plan with a student alongside Assistant Vice President for Enrollment Jed Liston (right).

As tuition increases and federal and state grant money decreases, students are taking out more loans to help pay for their degrees, says Mick Hanson, UM’s financial aid director.

“In the early eighties, fewer students used financial aid, and when they did, about seventy percent of the money was in the form of grants,” Hanson says. “Today about seventy percent is in the form of loans.” Twenty years ago, a maximum federal Pell Grant covered 158 percent of in-state tuition and fees at UM. Now it covers just ninety percent.

Added to that is the fact that Montana gives less than half of its regional peers’ average of need-based financial aid per student. In the 2007 fiscal year, Montana ranked forty-seventh in the country in appropriating state money for higher education.

But even though now it often means incurring debt, Hanson says the opportunities to get a higher education in Montana are better than ever. And given that a college graduate earns, on average, $1 million more than a high school graduate over the course of a lifetime, he says the investment is sound.

“I tell students, ‘don’t be gun-shy about borrowing what you need to invest in your future.’”

Economist Photiades agrees. “There are very few other ways that you could make as much money as by spending for an education,” he says.

And the benefits aren’t merely financial. “You will find ways of self-actualizing better—that’s beyond income. Not getting a college education stops that actualizing of potential.

“A college education is a value-added service, no different from using flour to make bread,” Photiades adds. “College processes a high school graduate into a human being that is more valuable.”

That value does not stop at the individual, according to Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer. “Montana is no longer just in competition with Colorado; we’re in competition with China,” he says. “We’re no longer just in competition with Indiana; we’re in competition with India. The best-educated work force wins in a flat earth.”

In his efforts to attract businesses to the state, Schweitzer says, he has to assure them there will be a pool of highly trained employees to draw from. The university system is pivotal in providing that.

He adds that he wants to see the Montana University System become “learning centers of the twenty-first century.” That means increasing efficiency by offering more online and distance learning opportunities, which don’t require many additional resources but can extend the classroom—and the tuition dollars—significantly.

Schweitzer initially alloted $35 million to higher education in his mid-November biennium budget. “It’s the second-largest increase for higher education in Montana history,” he said at the time. “These are austere times, but higher education is a priority.”

Of this $35 million, however, $23.4 million reflects the continuation of funds already appropriated to the MUS within the current biennium. The actual proposed increase over the last budget is $11.5 million—still only forty-three percent of what the governor’s budget office and MUS administrators deemed necessary to counter inflation.

When the national economic crisis began to hit Montana in mid-December, Schweitzer trimmed university appropriations by $13 million. While the final figure still awaits legislative decision, UM administrators say the governor’s budget doesn’t offer any new state money to keep pace with inflation and continue the cap on in-state tuition.

“At this point, for the university system, the budget is actually a slight cut from the last budget,” says Bill Muse, UM’s associate vice president for planning, budget, and analysis.

Montana Commissioner of Higher Education Sheila Stearns acknowledges the need to tighten the state’s purse strings. “It was a cautious budget, understandably,” she says. “We have to be cautious with our own pocketbooks, so we understand the state has to be thrifty as well. That said, we are very concerned about the pressure on tuition rates that will result from the governor’s funding decisions.”

Dame (far right) will graduate from COT in the spring and begin working as an apprentice with the Montana Carpenter’s Union.

Stearns says that the effects of the economic downturn on the MUS are just beginning to show. Students are losing jobs, parents are less able to assist their college-going children, and scholarships will be slimmer next year as university endowments feel the slump.

“At the same time, we’re not like a car dealership where the very next weekend you have half as many people coming in kicking tires,” she says.

Added to the economic woes are the decreasing numbers of high school graduates in Montana. There are currently 10,000 high school graduates each year in the state, of which fifty-four percent go on to higher education. But as Montana’s young population decreases, high school graduates are expected to decrease seventeen percent by 2015.

And those who are graduating aren’t taking their college decisions lightly, according to Tri Pham, a college counselor at Missoula’s Sentinel High School. Pham says the students he talks to are sincerely worried about the cost of a degree.

“The thing I’ve heard most from students is, ‘Is there going to be financial aid available from the government?’ I don’t have the answer to that,” he says.

One student Pham counseled had $12,000 stashed away in her college fund. As the stock market collapsed, that sum shrank to $7,000 in four months. “She’s really confused about what to do right now,” he says.

Pham says his students are asking him less about the experience of being in college and more about the careers that will come at the end of it. “I’ve heard some parents and kids be very pragmatic about it. They say, ‘I want to go to a school that can get me into a good job.’”

UM President George Dennison says that even in hard economic times, he advises high school graduates to pursue higher education. “Protect your options and go to college,” he says, “because the twenty-first century demands at least some college.”

UM College of Technology student Jenny Dame is looking to start a new carpentry career. Dame, a former Stimson Mill employee, went back to college last year.

Despite Wall Street woes that shrunk the UM endowment by 6.6 percent ($7.9 million) in the last fiscal year, Dennison remains optimistic about higher education in Montana. But the challenges underscore his sense of mission.

“This is the only developed country where the older generation is better educated than the younger,” he says. America has dropped from first place in the world to tenth in the overall education attainment of its citizens, he adds. The state’s colleges and universities have their work cut out for them, but Dennison says that the current financial troubles are survivable.

“I don’t believe that this financial crisis will mean student financial aid will dry up,” he says. “So what we do is keep doing what we’re doing to make college accessible. There are ways you can go to college, and we will help you figure it out.”

Montana State University President Geoff Gamble says that his university is stepping up its outreach to high schools and even middle schools to ensure more Montana high school graduates enter higher education in the state, a vital component to a university system that relies on resident students to fill its classrooms.

Gamble is readying himself for the impacts the economic crisis will have on MSU. “I think we’re going to see a pretty lean financial situation and maybe some belt tightening,” he says. Gamble admits that some new programs will have to be postponed until the financial situation improves and that the university will have to streamline its operations to cut costs. The MSU endowment was down 4.5 percent in the last fiscal year, a paper loss of $5.4 million. At the same time, Gamble is not discouraged.

“Patience will show that these things come back,” he says.

Both university presidents agree that the returns are good for investment in the university system, which not only prepares high school graduates for a career but also retrains adults looking to acquire the skills to get a new job in tough economic times.

Through The Years

The enrollment rate at UM has grown exponentially in its 116 years as an institution. Fall 2008 enrollment levels were record high.

“You have more and more displaced people joining the two-year programs to get back into the work force,” Dennison says.

One woman who came to college to kickstart a new career is Jenny Dame. Dame is in her second year in the carpentry program at the UM College of Technology. An employee at the Champion and Stimson mills for thirty years until Stimson finally shut down, Dame lost her job in summer 2007. She always knew how to pound a hammer, so she enrolled in the carpentry program in the hopes of starting a new career.

One frosty, sunny morning in November, Dame is in the attic of a house on Blue Mountain with a dozen fellow students breathing vapor in the cold air that smells like sawdust. She has a tool belt around her waist and lumber in her hand. Around her hammers pound, saws whir and students shout measurements to one another above the din.

“It was kinda weird going back to school after all these years,” Dame admits. “But everyone has been very supportive.”

When Dame finishes her degree in the spring, she’ll move into an apprenticeship with the Montana Carpenter’s Union. There looks to be plenty of work ahead, and Dame is pleased about what a college degree will say about her.

“It’s going to tell my employer that when I start something, I’m going to finish it,” she says. “It’s another feather in my cap. And plus, I’m learning.”

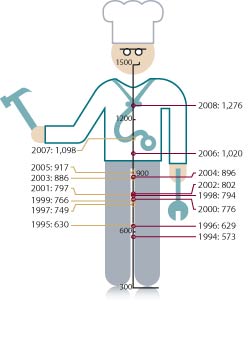

UM’s College of Technology Fastest Growing MUS Unit

Barry Good, the dean of the UM College of Technology, has a picture sitting atop the radiator in his office that he looks at wistfully from time to time. It is an artist’s rendition of a building that does not yet exist, a $32.5 million structure that Good hopes will house the future of his college.

Offering practical skills in a plethora of fields, UM’s COT has grown faster than any other entity since joining the MUS in 1994. The graph above shows the amount of students per year taking a full-time equivalent course load.

For now, COT—the fastest growing single entity of the Montana University System—is quite literally bursting at the seams. Duct tape holds together the carpet in the hallways and student lounge area of the administrative building on the East Campus, which murmurs like a small-town high school cafeteria.

In the parking lot outside, trailers serve as overflow office and classroom space for a college that has almost doubled its student population in ten years. The East Campus is hemmed in by the Missoula County Fairgrounds and Sentinel High School.

“We can’t expand, we’re landlocked,” Good says wearily. “Do you think that people in higher education should be in trailers?”

The proposed building, designated a top construction priority by the Montana Board of Regents, would be constructed on the South Campus, now occupied by the UM golf course. It would take four to five years to complete.

“It makes a great deal of sense to provide these facilities,” UM President George Dennison says. “There has been no investment in the College of Technology for twenty years.”

COT’s thirty-five different programs are drawing large numbers of students looking to acquire the necessary skills to start a new career.

“I’m pointing a lot of kids to the College of Technology because it’s affordable, and it’s a great springboard,” says Tri Pham, a college counselor at Sentinel High School.

For now, however, the new building remains only a picture on Dean Good’s radiator. The facility is not mentioned in Gov. Brian Schweitzer’s new two-year budget and is unlikely to be introduced in the next legislative session.

“That’s asking for a lot in these austere times,” Schweitzer says.

Jacob Baynham graduated from the UM School of Journalism in 2007. He spent the following year freelancing in Asia—from Hong Kong to Afghanistan—publishing his stories and photos in the San Francisco Chronicle, the Toronto Star, the San Antonio Express-News, and Newsweek. He is currently a news editor with University Relations.

Jacob Baynham graduated from the UM School of Journalism in 2007. He spent the following year freelancing in Asia—from Hong Kong to Afghanistan—publishing his stories and photos in the San Francisco Chronicle, the Toronto Star, the San Antonio Express-News, and Newsweek. He is currently a news editor with University Relations.