Fall 2001

CONTENTS Leaving Life in the Parking Lot

Where is the Parking Lot?

Fighting the World's Fight

Diva in Her Own Right

AROUND THE OVAL

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

BOOKS

SPORTS

CLASS NOTES

ALUMNI NOTES

Contact Us

About the Montanan

PAST ISSUES

Fighting the World's Fight UM's Rhodes Scholars by Caroline Lupfer Kurtz

The University of Montana has a phenomenal record of producing Rhodes scholars. Twenty-eight men and women have received the prestigious award since 1904, the first year the competition opened to American students. As a result, UM currently ranks fifth among public institutions in the nation (excluding military academies) and is nineteenth overall. Such an enviable record says many things about both the students and the University, according to philosophy Professor Tom Huff, who has helped shepherd applicants through the process for thirty years. “UM always has had a strong interest in public service (a key emphasis of the Rhodes program), reflected in the actions of the faculty and in the attitude of the administration,” he says. “Consequently, we attract socially conscious students and give them the education and inspiration to attain their goals.” Huff notes that UM faculty are able to give the individual attention necessary to allow students to shine academically and “students who come here, and those from Montana in general, are usually unpretentious, straightforward, easy-to-talk-to people, and they end up doing very well in the interview part of the process. [UM] is not a place that teaches elitism.” As secretary of the state committee responsible for choosing candidates to send to the district level, Huff believes that, in addition to their academic records, UM students’ ability to think on their feet and stand up for their opinions often gives them an edge in the selection process.

Identifying and encouraging Rhodes candidates is the job of the entire UM faculty, says Maxine van de Wetering, a retired philosophy professor who helped many students become Rhodes scholars over the past two decades. “I got involved because I was interested in getting students into programs abroad. I felt it was so important for Montana kids to gain a wider world view,” she says. Students who are not afraid to take risks academically, “who are interested in exploring the nature of knowledge and the meaning behind things” are students she felt would benefit from the Rhodes experience. “In particular, we looked for students with some kind of ethical standpoint or commitment,” she says, “a willingness to make a judgment for right or wrong.” How does the experience of being a Rhodes scholar stay with people? “I believe we all feel it every week of our lives in one way or another,” says attorney Jim Murray. In friendships made, doors opened, horizons broadened, the opportunities discovered at Oxford can be life-changing. As the following stories illustrate, UM’s Rhodes alumni have taken many paths to realizing Cecil Rhodes’ vision that they become champions of just causes and “fight the world’s fight.”

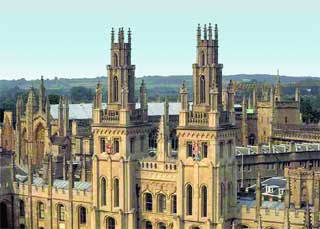

The Ex-PatriotsDavid Howlett David Howlett ’66 went to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar and never left. His offices are in the Bodleian Library, where for more than twenty years he has been editor of the British Academy’s Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. He also teaches Latin at Oxford, is a consultant to the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Medieval Latin from Celtic Sources and a member of the Institut de France in Paris, responsible for the Novum Glossarium Mediae Latinitatis, a dictionary of Latin usage in medieval times, and the Archivum Latinitatis Medii Aevi, a journal devoted to medieval Latin studies. It all might not have happened if his draft board had not changed his status in the late ’60s. Howlett recalls receiving his draft notice as he finished final examinations at Oxford. He went ahead with a planned bicycle tour of the Netherlands. On returning, he found that, without an appeal, the draft board had changed his status to “deferred for study.” “So I stayed on for a doctorate in medieval studies,” he says, “during which time I married an English girl, worked on a contract for the U.S. government at a U.S. Air Force Base, and got a job as the assistant editor of the Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary.” His assignment was volumes two through four, “but mostly on the stretch from ‘pray’ to ‘shitty,’ my last word,” he says.

Although most of his childhood was spent in Billings, traveling only as far as one set of grandparents in South Dakota and the other in the Flathead Valley, Howlett has thoroughly taken on the coloration of life in an English university town, one that dates back to the middle ages, his preferred milieu. “What I do professionally is also what I do in my spare time,” he says. “I write books about what happened when my English, Scottish and Irish ancestors first came into contact with Latin Christian culture from the Mediterranean.” These ancestors, Howlett says, “were drawn from barbarism into a view of the world as a created artifact, sung into existence in seven days by a God who created seven planets, which, as each circled the Earth in its crystal sphere, made music — the music of the spheres — there being, of course, seven notes in the gamut. . . . “Knowledge, too, was organized in the seven liberal arts, identified with the seven Pillars of Wisdom in Proverbs . . . all conceived as reflections of the mind of God expressed in number. “For those who saw through eyes conditioned by a biblical, platonic and ptolemaic view of the universe, number had the fascination that the DNA chain has for us. It afforded a window into the structure of the universe.” Howlett has contributed chapters to twelve books on such subjects, and he has ten of his own, the most recent of which, Pillars of Wisdom: Irishmen, Englishmen, Liberal Arts, is due out in 2002. And, of course, he lectures on all these topics.

“Always such a pleasure to be paid to talk,” he muses.Ann Haight

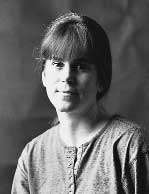

Soon after completing her doctorate at Oxford, Ann Haight ’78 began developing learning materials for England’s newly organized Open University. Although she had benefitted from one of the most selective awards in academia, Haight chose to devote most of her professional life to a very different sort of educational model — one that reaches out to all segments of society. The Missoula native was UM’s first female Rhodes scholar, and she blazed a strong trail. Women were first permitted to apply for the scholarship in 1976. Since, more than half — five of UM’s nine Rhodes scholars — have been women. Haight describes the Open University “as a way to bring higher education to the broadest group of people in a country where such education previously had been very elitist.” The Open University takes all comers, Haight says, and is based on the idea of distance-learning. The concept allows people anywhere in the country to study independently, using materials sent to them or, more often now, via computer. The success of the approach required special types of curriculum materials and study tools, which Haight created. Since its inception, the Open University has graduated hundreds of thousands of people and effectively forced other universities to liberalize their admissions policies. Haight left the Open University after four years, but has continued as a writer and editor on similar projects for other employers. One project involved frequent travel to Romania to produce education materials for that country’s banking industry, which, she says, “desperately needed to train a new generation of professionals to build up its infrastructure following the collapse of its command economy.” Her time as a Rhodes scholar gave Haight the opportunity to experience a different culture — one that she was “very attracted to.” By the time she left Oxford she had married Englishman Graham May; the couple have an eleven-year-old son. “There is a cliché version of Britain, as there is most places.” she says, “I live in this cliché of cricket fields and village greens, churches and ancient castles. But I’m also part of a gritty, modern Britain, a healthy multicultural Britain, and I’ve become very integrated into my community.”

The AdvocatesCharlotte Morrison

Many Rhodes scholars go on to attend law school after Oxford, one reason being the power of the legal system to effect social and political change, says Charlotte Morrison ’93, a Whitefish native and UM’s most recent Rhodes scholar. Morrison received her law degree from New York University in 2000 and immediately went to work as one of four law clerks for appellate Judge Rosemary Barkett of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Her clerkship coincided with one of the biggest legal controversies in recent years — the hotly contested presidential election results in Florida. The hearings (on the election outcome) were held before all twelve active judges of the Eleventh Circuit, instead of just three or four who typically hear cases at one time, she says. “All the judges were working on the election cases and everything else was just shoved aside. You can’t imagine the amount of paperwork coming in. Hundreds of pages every day that had to be read and dealt with. Just trying to keep on top of that, plus do research on the issues with all the political and media attention — it was crazy.” Morrison and colleagues found themselves continually tuned to radio reports and CNN because, she says, “they were finding things out before we could. We were writing opinions based on CNN reports.” The furor in Florida lasted a month and a half, but it seemed like forever, she says. Morrison now is participating in a two-year fellowship at the Equal Justice Institute in Montgomery, Alabama. The institute, headed by one of her NYU law professors, represents death-row prisoners in habeus corpus appeals, which are challenges both to the conviction and the constitutionality of the sentence, according to Morrison. Alabama does not provide counsel for defendants during appeals, she says, and actively caps pay at $1,000 or fifty hours for attorneys doing capital defenses. Consequently many prisoners awaiting the death sentence did not have the benefit of proper representation. Among her fellow Rhodes scholars, she says, “people had widely different and strong opinions about what it meant to be a leader, to be in public service. Their views were very different from my conception. I met people for the first time with real political aspirations, which had never occurred to me, but they thought the most effective way to create change would be as elected representatives. My experience in Missoula and since has been more of a grass-roots approach to social change.” Jim Murray

At one point Jim Murray ’76 had political aspirations. The summer of 1972 he left his home on a wheat farm outside of Froid to attend the Democratic National Convention. At eighteen, he was the youngest delegate for George McGovern. Although he continued to be active in student government after enrolling at UM, he soon realized his true passion was not politics but law and the legal philosophy underlying political action. Following Oxford and a year at Harvard Law School, Murray’s career soared as he was hired as a trial attorney by the largest law firm in Washington, D.C., and then hand-picked for a special, two-year assignment with the FBI. Recently, not content with past achievements, he traded security for the risks of starting all over again. Being a Rhodes scholar gave Murray a new view of himself and his roots. “That was absolutely my first time out of the country,” he says. “I remember clearly being very conscious of defending Montana. I’d never even been aware that I was from Montana before.” A year after leaving Oxford, Murray moved to the nation’s capital to work for Covington & Burling. A short time later, he was picked to be a special assistant to William Webster, advising the then-director of the FBI on criminal investigations. “I think this was a good example of the Rhodes network at work,” Murray says. “It was a spectacular job. Webster wanted the critical, outside eye advising him, and he only wanted you there for two years. Once you stopped questioning (whatever the FBI was doing) it was time to move on.” He returned to Covington & Burling and became a partner in 1990. His mentor was Charles Ruff, principal counsel to President Clinton during his impeachment trial. Murray remembers working with Ruff on a bank fraud criminal case. “He [Ruff] devoted as much energy, thought and grace to that closing statement — for an unknown, unheralded lost soul — as he did to the one he gave in the Senate,” Murray says, crediting Ruff with teaching him “a lot about judgment and life’s circumstances.” In 1996 he and two colleagues from other law firms decided to leave their secure niches and strike out on their own. “Life was very good at our firms and only going to get better, but we were too young to go on autopilot,” he says. “Basically we’ve had to prove ourselves all over again and it’s been worth it.” Murray and partners located their new litigation firm in Seattle. “We handle cases for Boeing, Weyerhaeuser and Costco, but also have the freedom to represent small organizations, individuals and nonprofits,” he says. Trial work is why Murray loves the practice of law, and it directly relates to his philosophy training. “Half of legal practice is worrying about other people’s problems out of a desire to do what’s right, not just what’s expedient,” he says. “We come in daily contact with human problems when they have become extreme. Our job is half counseling: Do you want to engage in this fight? Do you really want to say that to this person?” Early in his law practice Murray thought he eventually would head back to academia. “There was a time when I only wanted to teach, and that is due entirely to professors I had at UM,” he says. “I learned from world renowned minds in legal philosophy at Oxford, but the best teachers I ever had were at Montana, because they were so devoted to it.”

Caring for OthersMark Peppler

The first science major to be picked as a Rhodes scholar from Montana in forty years, Mark Peppler ’73 earned a doctorate in pathology at Oxford. Today he is a professor and medical researcher at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. There he is fighting the world’s fight by working to develop a new vaccine for whooping cough appropriate for use in the developing world. Busy with the full complement of teaching, research and administration, Peppler still finds time to visit grade schools to promote awareness and understanding of the microbial world, and in his spare time he has created a set of unique “flash cards” of microorganisms for medical and nursing students. Peppler met his future wife, Ronnene Anderson, a UM journalism student, while they were undergraduates, and the two had planned to marry right after college. At the time, however, Rhodes scholars were not allowed to be married during the first year of the scholarship. “So Ronnie met me in Oxford on New Year’s Day 1974, and we were married the next day,” Peppler says. “Two years ago we went back to England and celebrated our twenty-fifth anniversary with our old landlord and the vicar who married us!” After Oxford, Peppler entered a postdoctoral fellowship at the Food and Drug Administration, then was hired by the Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Hamilton. “We were both happy and anxious to get back to Montana and our roots,” he says. Peppler’s thesis at Oxford had been on natural bacteriocidal mechanisms, or how the body fights Neisseria menigitidis, the bacterium that causes meningitis. During the four years Peppler spent at the lab, he switched his research focus from meningitis to whooping cough. Peppler’s research with whooping cough — Bordetella pertussis and related species — focuses on how the organism infects cells and how its virulence is controlled. Producing the sort of refined vaccine used in the United States is expensive, he says, and requires a series of three injections at specific times, making it too costly and difficult to use in developing countries where a child is lucky to see a doctor even once. He and colleagues are trying to develop a vaccine that will work as an aerosol, which could be given as a one-time nasal spray. An added benefit, he says, is that each child carries the vaccine home and spreads it to siblings by sneezing or coughing, providing a booster dose. So far the data seem good, “but we want to be sure we’re not pawning off something that is second rate,” he says. Drug companies are not interested in such a product because there is no profit in it, he says. So Peppler believes it falls to him and others like him to try to do something about it. “We’re hoping to go to countries that would benefit most and help them develop it themselves,” he says.

David Wheeler The first response of David Wheeler ’88 to the suggestion that he apply for a Rhodes scholarship was “absolutely not,” he says. “I was planning to get married right out of school (to classmate JoAnn Paprotny) and at that time you weren’t allowed to apply for the scholarship if you were.” It wasn’t until a few days before the deadline, he says, that faculty members persuaded him to at least complete the application. He wrote his essay the night before it was due, interviewed with the state committee and was selected as one of two scholars from the district. “The wedding had to wait a year,” he says, “which in retrospect was a good trial for us.” Wheeler spent two years at Oxford gaining a master’s degree in physiology with an emphasis on the brain — quite a distance from the person who at one point was so disenchanted with education that he never finished his sophomore year of high school. Once married and back home, Wheeler entered graduate school at Stanford University to work on a nine-year combined degree, first getting a doctorate in neuroscience and then receiving his doctor of medicine degree in 2000. He now is embarked on a three-year residency in neurology at Brigham and Women’s and Massachusetts General hospitals in Boston. Although Wheeler’s Stanford research focused on how changes in the strength of the brain’s electrochemical signals relate to memory and learning, he now is more interested in clinical questions such as what happens in Parkinson’s disease or epilepsy. “I’ll have to make a decision in three years whether to focus on basic research or clinical medicine,” Wheeler says. “It’s a difficult choice. I get a big kick out of caring for patients. Lab research is interesting but I was really surprised by how rewarding taking care of people is.”

A Voice for PeopleSterling “Jim” Soderlind

Sterling “Jim” Soderlind ’50 recently retired from a long and distinguished career as a journalist and executive with The Wall Street Journal. He was “aided mightily” by his Rhodes scholarship, he says, “because I became a much better educated person.” Soderlind was born in the tiny town of Rapelje and grew up mostly in Billings. His undergraduate career interrupted by the Second World War, Soderlind returned to UM in 1948 to finish a degree in journalism, then sailed to Oxford in 1950. He relished the chance to see more of the world. “A good part of the value of the scholarship was travel,” he recalls. “You only go to college about twenty-six weeks a year. You’re expected to do a lot of work, a lot of it on your own, but you also had the ‘vacs.’ In 1950 and 1951 Britain was still suffering mightily from the ravages of the war, rationing was very severe and a good many students took off for the continent.” Armed with two suitcases, one full of clothes and one full of books, Soderlind explored the Mediterranean countries, eventually working his way up to Vienna, which was under Russian authority at that time. He returned home in 1952 and worked for three years as a reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune before he joined the staff of The Wall Street Journal, first covering furniture and the appliance trade in the Chicago bureau — “big stuff back then,” he says. He soon was promoted to bureau chief and sent to Jacksonville, Florida, where he wrote stories on segregation and the civil rights movement from a business/economic viewpoint. Soderlind rose through the ranks at the newspaper, becoming managing editor and editor of the front page. He helped guide the paper through an important evolution. “These were the years of broadening coverage, from just reporting financial news to covering the political and cultural scene as well,” he says. Soderlind says that many of his Rhodes classmates became scientists, scholars and teachers in fulfilling Cecil Rhodes’ directive. He chose journalism because “there’s probably no other medium where you’re closer to the public.”

The World’s BusinessKent Price

Kent Price ’65, M.A. ’66, got a sudden reminder some years ago of his Rhodes pledge to fight the world’s fight when he received a call for help from an old friend highly placed at the Bank of New England. At the time the bank was on the verge of the largest bankruptcy in history, Price says, and he was disinclined to get involved. “My friend reminded me that sometimes you have to put personal interests aside and take a lap around the block for your country,” he says. So Price put his expertise in finance and management to use to help restructure the bank for its eventual purchase by Fleet Bank. Price has made a long and highly successful career out of taking care of the world’s business. After UM and Oxford, where he studied modern history, he spent sixteen years in international finance at Citibank in New York. Since, Price has been vice president and chairman of a British power-storage company, president of an investment management firm in San Francisco, and chairman of a private bank there. Following his efforts with the Bank of New England, Price was approached by IBM’s chairman to help with some overseas problems. “I ran part of their business for four years, living in Tokyo and Singapore,” he says. “Eventually I got tired of all this moving around and came back to San Francisco to run it from there.” Price retired from that job a couple of years ago and now heads a company called Parker Price Venture Capital, which invests primarily in high-tech enterprises in the Bay Area. He recently spoke at a workshop on venture capital sponsored by the UM-based Montana World Trade Center. “About fifteen years ago I decided I was doing well enough to start helping others,” Price says. He has been a director of the World Wildlife Fund, on the board of local hospitals and is a faithful donor to UM’s business school. Recently he became a UM Foundation trustee. “I’ve been honored and delighted to help out,” he says. “I’ve had so many opportunities to do things, and much is due to the nurturing I got at UM. I’m not sure I would have gotten that any other place.” Caroline Lupfer-Kurtz is a frequent contributor to the Montanan as well as UM’s Research View and Vision.

AROUND THE OVAL | SPORTS | CLASS NOTES | ALUMNI NOTES

|