Winter 2001

CONTENTS

Managing the Mountain

Teachers Who Change Lives

AROUND THE OVAL

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

UM FACES

SPORTS

CLASS NOTES

ALUMNI NOTES

Contact Us

About the Montanan

PAST ISSUES

From hand-pulling to sheep-grazing to biocontrols, it takes a village to manage a mountain. By Kerry Thomson The walk to the M is getting even prettier these days. The dull gray haze of spotted knapweed that has threatened native plants in recent decades is slowly losing its choke-hold on Mount Sentinel, thanks to weed-pulling efforts of locals and the hard work of UM researchers like noxious-weed coordinator Marilyn Marler.  Marler and other scientists have spent the past couple of years tackling weeds from a number of angles: they’ve mowed acres of weeds, pulled them by hand and borrowed local sheep to graze in the spring. They’ve sprayed herbicides and even collaborated with moths, beetles and flies in the fight to restore the mountain’s prairie. Weed control in the Missoula Valley is a relatively new concept that appeared when the Montana Legislature passed a bill in 1995 mandating that public agencies control weeds on state property. However, what appeared on paper to be a fairly straightforward task materialized as a complicated endeavor. In places like Missoula where many locals — and researchers — decry the blanket-use of herbicides, researchers looked for other ways to curtail the weed invasion. “People do really use those lands (and) most people have a strong opinion about them,” Marler says. “I think that reflects well on people — that they’re not apathetic.” Marler has tested a number of control methods, starting with the simplest and arguably the most successful — hand pulling. She started with the M-trail because high levels of people and dog traffic made other control methods unworkable there. In 1999 Marler started bringing volunteer organizations to the mountain to participate in her “Adopt a Switchback” program, a unique solution that relies on community members to remove — plant by individual plant — each spotted knapweed along the steep path. “Almost every single switchback has been adopted (by an organization) and it looks a lot better,” Marler says. “After one year of weed pulling there’s a dramatic difference.” But if there’s one thing Marler and researchers like Diana Six, assistant professor of forest entomology and pathology, have found, it’s that no one approach to weed control has proved a cure-all. “I think a lot of people are still looking for the silver bullet,” says Six, who has spent the past couple of years experimenting with yellow knapweed moths. “If anything, the research over the years has shown that no one thing is working well.”

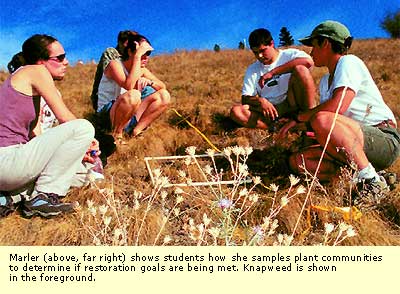

Marler, who runs her own experiments, oversees her student researchers and coordinates other research projects, agrees. “Hand pulling on the M-trail is tremendously successful, but I really wouldn’t recommend that for the top of Mount Sentinel,” Marler says. The mountain is just too steep, and there’s too much land to make hand pulling elsewhere anything but a nice ideal. Just as the landscape around Missoula varies acre by acre, so, too, will the best methods for controlling weeds on those lands. Weed control has become a big issue in Missoula County, where spotted knapweed, leafy spurge and Dalmatian toadflax have obliterated historically diverse communities of bunchgrasses and perennial wildflowers. On city-owned Mount Jumbo as well as on Mount Sentinel, where the University owns more than 500 acres, the problem is acute. “Some days it’s just really discouraging,” Marler says. “It would have been so much easier and less expensive if somebody had started twenty years ago.” In agricultural parts of the state, farmers and ranchers have long known the value of keeping weeds in check. But in more urban areas like Missoula, the need to control weeds hasn’t been as strong. “Missoula County is kind of notorious in the state of Montana for not managing its weeds,” Marler says. “If you travel to any other county in Montana you won’t see the level of weeds you do in Missoula.” Soon after the 1995 legislation passed, UM developed a weed management program for Mount Sentinel. Marler was hired part time to oversee the program in 1998. The following year, the city brought her on board to bring the leafy spurge and Dalmatian toadflax epidemic on city-owned parts of Mount Jumbo under control. Marler embraced the challenge. A native of California who earned her master’s degree in ecology at UM, Marler grew up in a state where weed problems are as common as shopping sites on the Internet.

She began orchestrating a two-pronged approach to the problem. While Six, other professors and a handful of graduate and undergraduate students used sheep, chemicals, bugs and — as a last resort — lawn mowers to rid the mountain of knapweed, Marler added her own insights and research for weed control. She also explored the best routes for bringing native plants back after the weeds were removed. Sometimes, she says, native plants will bounce back if the weeds are killed off. But in areas where weeds have all but wiped out the native plants, managers have to give native plants a head start by reseeding the area. “A lot of places you can spray and then let the native plants just come back on their own,” she says. “In Missoula County our situation is well developed. There’s just nothing else there anymore. We have a lot of places where there is a lot of knapweed with no native plants and it [reintroduction of native plants] needs help.” Across town at Fort Missoula Marler is helping raise native plants grown from seed or donated from new-home construction sites in the town’s South Hills area. The goal is to collect seeds from the plants so the mountain can be reseeded with native species that have adapted to the area. “It’s really an exciting project because it allows us to use the local ecotypes of species instead of store-bought varieties,” Marler says. Back on Mount Sentinel, several studies are being used to find the best combination of methods for weed management. Marler oversees those projects to ensure researchers don’t accidentally contaminate other studies by, say, spraying an area where another scientist is testing the effects of gall fly larvae on knapweed seed production. Researchers begin their studies on the mountain each spring, just as knapweed begins growing and before it blooms. Early this year, some ninety sheep dotted the hillside as knapweed and leafy spurge emerged from their winter slumber. They came on loan from a local rancher and, though the sheep steered clear of the leafy spurge, they appeared to nibble contentedly on the knapweed. “I think they did a good job of grazing about 30 acres,” Marler says. But introducing sheep to the mix also created some challenges. There were problems with dogs chasing or killing sheep, and then there was the question of if the sheep were causing unnecessary erosion when allowed to graze in steep areas. That is one of the many reasons researchers are testing other control methods, Marler says. Come summer, when knapweed goes to seed, research shifts to other tactics such as herbicide spraying, mowing and the introduction of insects. Bugs have proved useful, although how useful isn’t yet clear. Six, for example, spent the last two summers studying the yellow knapweed moth which, as a caterpillar, eats knapweed roots. Six wanted to see how the moth’s impact on the weeds varied based on how many moths are released into an area. She also wanted to know how well the populations would be doing one year after introduction. Unfortunately, during both study seasons, fire dangers closed Mount Sentinel about the same time new moths emerged, and Six hasn’t been able to assess her project during its critical time frame. “It’s kind of hard to work on that mountain because you can be shut out at any time,” Six says. Now she says she may have to base her analysis solely on information she’s gathering from a replicate study site up Rock Creek. Still, insects introduced in the past couple of years do seem to be having some impacts on the weeds. North of the moth-release site, toadflax-eating weevils have, past summers, munched on Dalmatian toadflax while nearby weeds got a dousing with herbicides. At other plots, flea beetles have had a go at leafy spurge, and ovary-feeding beetles do “seem to be eating a lot of ovaries” on resident Dalmatian toadflax, according to Marler. While insects do their part to eradicate unwanted plants, other researchers are looking to see what effects the bugs might be having on the native plants. Beth Newingham, a biology doctoral student under Associate Professor Ray Callaway, suspects when spotted knapweed gets eaten, it not only may grow more as a result, but may have a negative impact on neighboring native fescue plants. Newingham started her research in a University greenhouse, placing knapweed and fescue side by side in some containers, and knapweed by itself in others. When she trimmed leaves off the knapweed to simulate what deer or bugs might do, she made a surprising discovery. In containers where only knapweed had been planted, the plants didn’t grow much after being trimmed. But in the containers that had both knapweed and fescue, the knapweed actually had a growth response after getting clipped. Instead of being negatively affected by trimming, the knapweed appeared to do better. “It actually benefits from the fescue being there,” Newingham says. “Since we’re seeing a compensatory growth response by [knapweed], we’re getting the exact opposite results that we expected and that may have indirect effects on the fescue.” To test the phenomenon further, Newingham has moved her research outdoors to Mount Sentinel where she’s monitoring how knapweed and nearby fescue respond when the knapweed gets clipped. Her goal is to see if biocontrols, like insects, could indirectly be harming native fescues when they dine on knapweed. For the moment, however, most of the mountain’s study sites are focused on finding the best methods for removing knapweed and other exotic species. At some study sites, researchers test several methods simultaneously. In some cases it will take several years of experiments before scientists will know what combination of controls works for a particular site. Even when scientists divine the best plan of attack, it’s not going to make weeds disappear instantaneously. “We’re not going to just wake up next spring and it’ll be all taken care of,” Marler says. She estimates in five to ten years native species will take a much larger share of the mountain. “I think it’s going to be constant effort to deal with the weeds, but I still think it’s possible to restore those communities and get them looking a lot better than they do now,” she says. Kerry Thomson ’92 is a recent transplant to the Oregon coast, where she works as a health reporter for a publishing company. AROUND THE OVAL• SPORTS • CLASS NOTES • ALUMNI NOTES FEEDBACK•STAFF • ABOUT THE MONTANAN •ARCHIVES HOME • CONTENTS

|