Fall 2000

CONTENTS

Start-Up Savvy

Saving Virginia

Campus Clues

AROUND THE OVAL

UM FACES

SPORTS

CLASS NOTES

ALUMNI NOTES

Contact Us

About the Montanan

PAST ISSUES

Fall 2000 CONTENTS Start-Up Savvy Saving Virginia Campus Clues AROUND THE OVAL UM FACES SPORTS CLASS NOTES ALUMNI NOTES Contact Us About the Montanan PAST ISSUES |

by Joan Melcher Photos by Kelly Spears

I hear boys' voices echo as they run under the balcony and on down the street. I wonder why they sound different from boys' voices elsewhere. Then I remember - they're running down a wooden sidewalk, and the hollow pacing resonates with their young voices to produce a familiar sound in an eerie rendering. There's a sensation of timelessness. But the feeling today is not that time has stopped; something is actively pulling me back. The past has a grip on Virginia City. Alder GulchSo their partners found the two of them sitting by the fire, chores undone. Grumpy because they had not panned a flake of gold, the four grumbled some about partners lazing among dirty dishes while the horses were still uncared for. Bill handed them the pan with their gold samples to shut them up. - Gold Camp I'm sure most women would find it charming that a domestic dispute among miners was at the center of the discovery on Alder Gulch. Also interesting to contemplate is that fair play and equality, two elements not often associated with mining boomtowns, appeared at the forming of the community. When Bill Fairweather and his five cohorts arrived at Bannack after their discovery, it seems they weren't able to keep their good fortune a secret for long and when they left before dawn June 2, 1863, to return to the gulch, they were followed by a good part of the town. Realizing their predicament, they held a miners' meeting wherein Fairweather said the gulch would be open to all if the group voted to guarantee the claims of the original six; the miners went them one better, releasing the discoverers from the obligation of representation work that was required to hold a claim. The rush was on.

The History

John Ellingsen moved to Virginia City in 1972 to work for Charlie Bovey and never left. Now he's curator of the Montana Heritage Commission restoration project and is known as a walking encyclopedia of Virginia and Nevada cities. Whatever you need to know - population statistics, renovations over the years, the numerous incarnations of a particular building, when displays were furnished - you name it, he knows it and can tell you in a flash. I stumble a little with the history of the town and he's quick to recite a few highlights: . . . the oldest continually inhabited mining camp in the West . . . probably the largest placer gold discovery in the world yielding treasure worth an estimated $2.5 billion (in today's dollars) . . . a population jump to 30,000 a year after the discovery, loss of more than half the population to Last Chance Gulch a year later . . . capital of Montana from 1865 until 1875, again losing out to Helena . . . a population low of 75 residents in 1943, stabilizing at 150 today - double that in tourist season. I admit I'm one of those people who sometimes thinks of Virginia City as a ghost town. Au contraire: it has been the Madison County seat for more than a century, and two nationally publicized trials have been held in its circa 1876 courthouse - the case brought against the "mountain men" who abducted biathalon Olympic hopeful Kari Swenson in 1984 and the civil trial in 1999 that pitted Charles Kuralt's daughters against his mistress and found the mistress to be the rightful heir of Kuralt's Montana cabin. Not much of a ghost town, I guess.

The Property Sue and Charles Bovey began buying Virginia City buildings and refurbishing them with authentic merchandise in the 1940s. I remember from childhood visits the town they preserved: the barber shop, the blacksmith's, Content's Corner - tiny-doored buildings framing displays viewed through musty windows. Returning to it is like visiting an old friend. And learning more about how it was preserved produces a feeling similar to learning the life secrets of an aging aunt. Everything is put in a different perspective. Ellingsen tells me how the Boveys not only bought, maintained and stocked the buildings and displays in Virginia City, they basically raised Nevada City from the dead, buying or assuming more than thirty structures from around the state, dismantling them, and moving them to recreate the town. With the death of Sue Bovey in 1988, Virginia City's fate rested with the Boveys' son, Ford. His parents' mission always had been to save the sites for the people of Montana, so Ford approached the state of Montana. Ellingsen remembers the date and time the Montana Legislature voted to purchase the Bovey holdings in Virginia and Nevada cities - 4:37 p.m., April 27, 1997. The purchase price was $6.5 million - $5 million for the artifacts; $1.5 million for the land and 249 buildings, including outhouses, sheds and back buildings. The most significant part of the purchase is what is referred to as "the lower block" of Virginia City. This block includes about thirty buildings that form the largest historic architectural group of its kind still in use in the American West.

The Curators I'm beginning to understand the sighs and the overwhelmed sense that came through in telephone interviews. As I talk with more people, I realize just how big this restoration project is - most of the buildings need to be stabilized before preservation or restoration can be considered; 200,000 to 300,000 artifacts must be considered and cataloged (compared to a total of 60,000 held in the state historical museum); funds provide for only a handful of staff; and a feeling of the past seems always to be pulling on the town, challenging change through sheer will of years.

Unlike many others, Ellingsen does not find the task daunting. A rare breed, he seems more comfortable in the nineteenth century than the twenty-first. He prints playbills for the Opera House and Brewery Follies on Montana's first press, the press that newspaper editor Thomas Dimsdale likely used to extole the virtues of the vigilantes. He drives a Jeep that appears to have barely survived the Korean War. He lives among the ancient, empty buildings in Nevada City in an 1895 ranch building he moved and rebuilt in 1975. He's not worried that so much needs to be done. It's always been that way. A Montana State University professor is taping interviews with Ellingsen for an oral history of the two cities. "He's got hundreds of pages, but we've barely scratched the surface," Ellingsen reports, with a complete lack of pretense or hyperbole. Few people could pull that off. But few who know him would argue. Ellingsen's passion is counterbalanced by the light-hearted but deliberate approach of the project's curator of collections, Pat Roath. "John is a traditionalist, and I come from a museum background," Roath says. "We're working really hard to make the two things meet without too much pain." Raucus laughter from both sides speaks for itself, but it's clear they're "family." Joining the project last fall, Roath moved into an impressive new 8,000-square-foot curator center, funded through the largesse of the late Lee C. McFarland, whose wife, Ruth, is a UM alumna. It's here that the thousands of artifacts will be taken, assessed and cataloged. Roath talks about "long-term museum practice" and "ethical considerations" to do with state monies and protection of artifacts. Roath held positions at the University of Indiana and the Mint Museum of Art in Charlotte, North Carolina, before returning to her native Montana. She explains that her role is to determine the value of the collection, which is based not on resale value, but on historical significance, relation to site, condition and redundancy. There is a lot of redundancy.

"We have at least one of everything and probably ten or twelve of everything," she says. "On the other hand, we do have some priceless one-of-a-kind things. But they're all out there in uncontrolled environments." Roath's first mission was to protect and inventory objects in the one hundred displays and concession sites in the two cities. With the help of two interns, she also has begun the arduous process of cataloging items. Key finds so far have been a commemorative button of Grant and Lee shaking hands at Appomattox in 1865 and a well-worn set of early-twentieth-century eastern European Tarot cards.

Preservation Jeff Tiberi, executive director of the Montana Heritage Commission, puts the project in perspective: "Everything needs attention." He tells me the first full season the state owned the properties was dedicated to fixing fifty roofs to secure building contents and establishing the commission, an eleven-person board named by the governor. Chief accomplishments of the second year were to build the curator center and rebuild the railroad tracks between the two towns. This year the park service has designated seven buildings that require immediate attention and is beginning work on them. More than 120 people have volunteered to help with maintenance and restoration work this season, including several Elderhostel groups. Coordinating their activities has become a full-time job. I sense Tiberi's relief when he reports a few weeks later that he was able to hire a volunteer coordinator through a grant from the Montana Historical Society Foundation. The foundation has raised more than $2 million for the project. But Tiberi estimates at least $19 million is needed just to stabilize buildings and artifacts. "The work load is onerous, but the project is so exciting, you just keep plugging along," he says.

The University UM has a long-time association with the two cities. Key imports over the years have been UM actors and musicians. Not surprisingly, I run into an actor friend a few minutes after arriving in Virginia City. He gives me tickets to the afternoon performance at the Opera House, where he performs with the Virginia City Players, the longest running professional acting troupe in the Pacific Northwest. The troupe has drawn heavily from the UM drama department since its inception forty-nine years ago. The Brewery Follies, a relatively new and ribald addition to town entertainment - best described as a Montana Saturday Night Live (but funnier) - also boasts several UM alumni. The Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research made a major contribution to the effort with a detailed study to help the commission plan for attracting more people to the two towns. Other contributions from UM include an intern who is helping Roath with curating duties and a four-week archaeology course focused on excavating areas around buildings chosen for preservation.

Community Finds

John Douglas, UM associate professor of anthropology, heads up the archaeological project with his wife, Linda Brown, a faculty affiliate. He tells me that several locals have come up while the students were excavating, mentioning that if they found some gold in the area to let them know because they had lost some there. But the study of archaeology is in some ways almost the antithesis of mining speculation. Douglas gets excited about finding the boardwalk to the Chinese Temple (unfortunately it extends under Highway 289, which runs through town), a buried walkway around the Gilbert House that was never known to exist, an 1847 penny in surprisingly good condition, the base of a teapot circa 1875, a Civil War button, a wooden handle to a Chinese toothbrush and a glass marker for the game of Fan Tan. Of course, he'd like to find a pot of gold or a cache of jewels, but mainly he's looking for "the ordinary things that piece together peoples' lives - what cuts of meat they ate, the contents of glass bottles, what ethnic groups there were and how they lived . . . ." He notes that his team has found notably few toys in Virginia City, and he ponders that while his own boys head out for a tour of the town. In the three weeks the students have been working in Virginia City, they've moved 250 cubic feet of dirt. Seeing them crouching over their digs or lying flat to carefully remove compacted soil while the sky spits rain, I wonder at their patience and forbearance and just how stiff they are by the end of the day. They just laugh it off, not wanting to go there. Melisse Pollard talks about the local people who come by. "They're real excited about the work we're doing," she says. "They bring us pictures to show us what it was like here." Trinity Schlegel notes that field work has added to her understanding. "All that stuff from class clicked for me," she says. "I get it."

The People

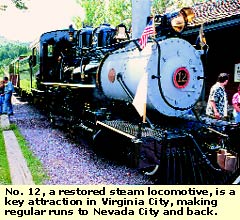

The licentiousness of a mining town is perhaps its most appealing quality. I'm not referring to the usual vices like prostitution, theft, opium smoking or public drunkenness; rather, the refreshing openness - the feeling that you can get away with stuff that might bring "looks" or regulators down on you elsewhere. For instance, food and drink not only are allowed in the Opera House and the Brewery Follies, they're encouraged. Actors sell popcorn at the door to the Opera House and push drinks inside the Follies during intermission. You know this is the way it was in the old days and it's surprisingly exhilarating to know your experience can be as raucous and immediate as it was then. You can cross main street in a few steps anytime, watching out for pickup trucks, tour buses, horses and buggies and half-block-long Winnebagos. You can contemplate the rope marks on cross beams in a building where road agents were strung up. You can ride the newly-restored steam locomotive to Nevada City and not worry about the miles of environmental degradation you see along Alder Gulch (it should be cleaned up, but this is history after all). In short, there's a freedom and a wildness to this past that can be intoxicating. And through it all flows a feeling of community, of belonging that harkens back to the miners' domestic squabble and the decision to open Alder Gulch to all takers, as long as there was fairness for the discoverers. The historical society calls Virginia City the "true cradle of Montana history," where our history began, the home to all that came later. I've learned through talking with Tom Cook, society information officer, that in Montana history has been preserved from the ground up, by individuals and communities; 165 museums and historical sites dot the state's landscape. People were saving history in Montana even as they were making it. The effect is that, in many instances, the old and the new sometimes seem like one and the same here. And although there has been talk of Virginia and Nevada cities' historical cache being worthy of development to a world-class historical interpretive site such as Williamsburg, Virginia, it occurs to me as I leave that if Virginia City is to be saved, most likely it will be saved - one day at a time - by Montanans.

Joan Melcher is editor of the Montanan AROUND THE OVAL• SPORTS • CLASS NOTES • ALUMNI NOTES FEEDBACK•STAFF • ABOUT THE MONTANAN •ARCHIVES HOME • CONTENTS

|